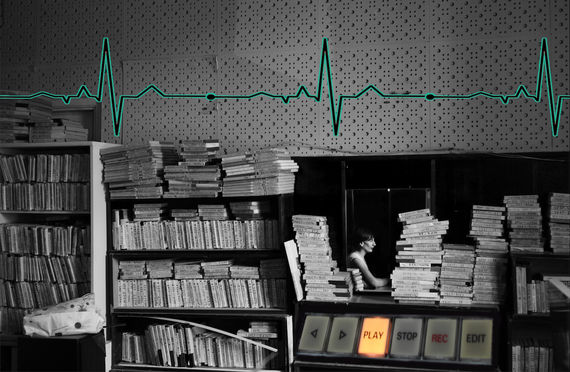

Ispiryan at the archives of the Public Radio of Armenia.

The tapes go through several steps until they are ready to be kept on hard drives. Once the format is changed, the digital file is sent to undergo the cleaning process.

Besides the records, the team also puts together the biographies of the artists and gathers their photographs.

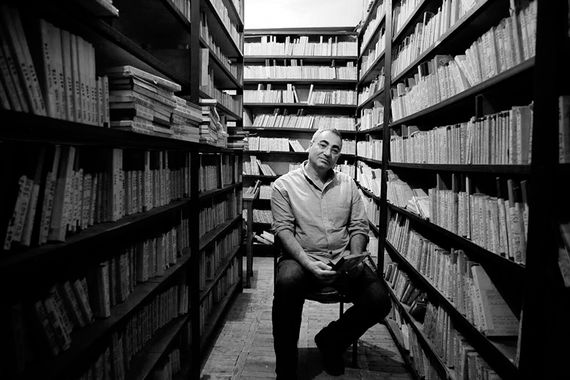

What happens when we search for Western musicians from the 20th century on the Internet? We typically get thousands if not millions of results including detailed biographies, video and audio recordings. What if we search for Armenian artists from the same period? We come across incomplete biographies, and if we’re lucky, we might find some videos on YouTube. It’s not because Armenia doesn’t have its legacy in folk music, jazz or classical music. It’s because thousands of audio tapes from the Soviet and post-Soviet years were locked in archive rooms until recently when Artur Ispiryan and his team took up the task of digitizing them.

The idea of digitizing the old archives goes back to 2001, when Ispiryan and Vahagn Hayrapetyan’s trio recorded a jazz album, a remake collection of songs by Alexander Adjemyan, Konstantin Orbelyan and Artemi Ayvazyan from the 1970s and 1980s. Ispiryan decided to release a second album, where, instead of referring to songs from the 80s, he went back to the 60s. Titled “Yerevan is Speaking,” the album brought together jazz interpretations of pop songs about Yerevan.

While working on the second album, Ispiryan became more and more enthusiastic about Armenian jazz and was determined to go back to its roots when Artemi Ayvazyan formed the State Jazz Orchestra in 1937. In order to complete his third album, “Once Upon a Time in Yerevan,” Ispiryan asked for help from Public Radio of Armenia. “I have always collaborated with the Public Radio as there were no other sources from where I could find the music I was looking for,” says Ispiryan.

In 2017, Ruben Jahinyan, the head of the Public Council of Public Radio, invited Artur Ispiryan to digitize 120,000 tapes that were in danger of being lost to decay. Having years of experience in digitization, Ispiryan came up with a plan to preserve the tapes. Once the technology was acquired, the team began the digitizing process immediately. They started off with Armenian songs and radio programs, which make up 30 percent of the overall archive. After finishing the Armenian section, they are planning to digitize Kurdish, Yazidi, Russian and Azerbaijani collections as well.

The tapes go through several steps until they are ready to be kept on hard drives. Once the format is changed, the digital file is sent to a special room where they balance the sound waves, remove all ambient noises and connect the separated parts of the record. Depending on the quality of the original tape, the cleaning process might take up to a whole working day. When the second step is done, the digital file is sent to the music library, where Ms. Ruzanna labels the records in three languages and adds them to the digital library.

While digitizing the records, the team came up with an idea to create a website to make all the records available to the public. Ispiryan believes that we should get rid of the mentality that archives must be inaccessible for people. “It’s due to that very inaccessibility that today we have bad music and that people do not know our great musicians,” says Ispiryan.

The website, which will be available to the public starting Feb. 25, 2019, has gathered records of songs and various radio programs. Available in three languages (Armenian, English and Russian), this website will give viewers a chance to listen to all the digitized music and radio programs. It has different sections based on music genres (jazz, pop, folk, classical, spiritual) and radio program categories (interviews, plays, poetry, programs for children). The last section, titled ‘Other’ will present non-Armenian (Kurdish, Yazidi, Russian, Azerbaijani) songs and programs once they have been digitized.

Besides the records, people can also find the biographies of the artists along with photographs. According to Nune Samvelyan, who is responsible for the website, the most challenging part of her job is the search for visual material. “There is almost no visual data both in the libraries and on the Internet, and I have to go from one house to another in search of old photographs,” Samvelyan explains. Sometimes she’s lucky, and the families of the artists share their photo albums after learning about the project.

Artur Ispiryan estimates that the digitization of the entire archive may take up to 4-5 years. However, it might take longer because many composers and their families are now bringing their own records to them after learning about the project. Through this project, Ispiryan hopes that the young generation will finally have better access to Armenian musical heritage. “We haven’t created a bridge between the past and the present so that our youth would be able to go back and see what treasures we have,” says Ispiryan, hoping that Armenian music will find the recognition it deserves.

Images and video by Gayane Ghazaryan.