What to Do?

The question of whether the Republic of Armenia should remain a member of the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) or leave is still being debated in Armenian political and analytical circles. This is largely due to the fact that Armenia is continuously faced with the imperative of building a security system to confront the external threats and challenges it faces following the 2020 Artsakh War. As the pre-war strategies, formulas and tools have proven to be ineffective on the ground, the state is seeking comprehensive solutions to maintain its sovereignty, territorial integrity and independence. However, this task has been made even more difficult by the geopolitical fluctuations brought on by the conflict between Russia and Ukraine, Azerbaijan’s land-grabbing policies towards Armenia, and its ongoing ethnic cleansing policy against Artsakh [Nagorno-Karabakh].

Opponents of Armenia’s withdrawal from the CSTO often present the following arguments:

- The CSTO did not provide assistance during Azerbaijan’s occupation of Armenia’s sovereign territory in May 2021 and September 2022, due to the Armenian authorities’ persistent harm to relations with Russia since the 2018 Revolution by pivoting toward the West. In order for Armenia to receive CSTO support based on the principle of collective defense, it must acknowledge its own share of responsibility, stop engaging with the West in a way that is inconsistent with Russia’s strategic interests, and return to the pre-revolution orientation between Armenia and Russia.

- The CSTO’s inaction is acceptable, but the current authorities are not responsible for it. Armenia should still not leave the organization, because the risks of doing so have not been assessed and such a departure could potentially escalate Russia’s punitive policy towards Armenia.

- The current authorities must be replaced by a political force aligned with official Moscow and capable of repairing Armenia-Russia relations. The key to resolving Armenia’s problems hinges solely on improving its ties with Russia. This entails abandoning or limiting relations with Western powers, addressing Armenia’s problems, devising solutions, and formulating strategic approaches from the perspective of Russia’s national security interests.

Proponents of exiting the CSTO argue the following points:

- The organization is not in line with Armenia’s democratic aspirations, due to the dictatorial regimes of its member states. If Armenia wants to integrate into the Western family, Armenia should leave the CSTO and contribute to the decline of Russia’s economic, political, and military influence.

- Armenia must minimize relations with Russia and deepen relations with the West instead.

- Armenia must leave the organization altogether and join the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) instead.

Despite their differences in emphasis, both groups are unified by one idea: they rely heavily on the Russian factor, whether in a positive or negative form, while creating provisions and justifications for Armenia’s continued membership in the CSTO or withdrawal from it. This article approaches the subject of remaining in or leaving the CSTO by developing a new national security strategy for post-war Armenia and reviewing Armenia’s positioning in international relations. It acknowledges that Russia, traditionally, has viewed the South Caucasus as its privileged zone of influence.

The Republic of Armenia has adopted two national security strategies. The first strategy, adopted in 2007, was intended to guide the state’s internal and foreign security strategy by identifying its key challenges and priorities. This document emphasized the likelihood of Azerbaijan using force against Armenia and Artsakh as one of the external risks to national security. However, the strategy also recognized numerous factors impeding such developments.

Part one of this article describes how Armenia has built its security system since joining the Russian-led military alliance, which is based on the principle of collective defense and bilateral military-political relations between Armenia and Russia. This principle is also included in the 2007 strategy, which regarded CSTO membership as a component of ensuring Armenia’s security and emphasized the importance of the provision on preferential conditions for military-technical supplies within the framework of the Treaty’s military component.

As a result, the military-political establishment considered the format of the OSCE Minsk Group co-chairmanship and Armenia’s membership in CSTO among the factors deterring Azerbaijan from using offensive action against Armenia and Artsakh.

The second strategy was adopted in 2020, months before the start of the second Artsakh War. The document emphasizes that since the adoption of the 2007 strategy, the international and regional security environment has significantly changed, making Armenia’s challenges more complicated and multidimensional. However despite this, Armenia failed to properly assess the security environment, as evidenced by Azerbaijan’s attack on Artsakh with the support of its strategic ally and NATO member Turkey, and the subsequent borderization and occupation of Armenia’s sovereign territories after the tripartite declaration on the cessation of hostilities on November 9.

During a session of a special parliamentary commission created to investigate the circumstances surrounding the 2020 war, Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan stated that relevant state bodies assessed the probability of war at only 30% until September 25, 2020 –– two days before the start of the war. Former Defense Minister Davit Tonoyan claimed that the Armenian Ministry of Defense did not predict that Turkish Armed Forces could operate so close to the military operations, using F-16 fighter jets that exposed Armenia’s entire air defense system. He also claimed that Armenia faced serious obstacles importing weapons during the war.

Armenia has never had a clear conceptual foundation for a national security strategy. Political thought has been limited to beliefs such as “Russia will never allow a war in the South Caucasus;” “Russia will support Armenia in the event of a military escalation, because Armenia is Russia’s strategic ally;” “The CSTO is a structure operating on the principle of collective defense, so aggression against Armenia’s sovereign territories will mean aggression against all member states;” “Joining the Eurasian Economic Union rather than the EU Association Agreement was aimed at strengthening our security;” among others. In other words, Armenia has increasingly relied on one strategic ally for its economic, political, and military needs, believing that doing so is its only salvation. If we could turn back the clock, Armenia should have at least refrained from extending its membership in the Collective Security Treaty in 1997, as Azerbaijan did, and instead should have started shaping its distinct place and role in the region.

The Republic of Armenia’s national security strategy can benefit from a variety of concepts working in complementarity. One such concept is Small State Specialization, which implies implementing strategic programs aimed at increasing standards of professionalism and taking on a leading global role in a number of areas in order to boost Armenia’s competitiveness in international affairs and establish its political and geo-economic value. For example, Estonia has been pursuing similar conceptual reforms to enhance its expertise in cybersecurity and robotics and autonomous systems (RAS) for military forces. Singapore has done so in digital control systems, and battlefield management technologies.

However, implementing this concept will be a difficult undertaking for Armenia, as it requires the state to consciously choose to favor strategic planning based not only on Armenia’s geographical location and geopolitical positioning, but also on more efficient use of its material and intellectual resources beyond classical thinking. Small states such as Israel, Estonia, Singapore, UAE, Azerbaijan, and others have succeeded in projecting influence within their political environment by adopting unorthodox solutions. At the same time, Armenia will undoubtedly face domestic opposition, including from a number of public circles and individuals operating in the interests of other states, on the path to developing an “out of the box” solution, as Small State Specialization will advance Armenia’s asymmetric and symmetrical foreign relations capabilities, significantly diminishing Armenia`s overdependence on Russia, leading some supporters of continued CSTO membership to try and “save” Armenia. People who continue to hold comfortable positions within state structures, may also join the circle of “saviors” since Pashinyan’s government’s approach of “laying everything bare” proved ineffective in changing the entrenched unresponsive working style of state institutions. Certain circles in the Diaspora may also exhibit partial resistance, as advancing the agenda of the Republic of Armenia beyond ideas like Armenian Genocide recognition will require accepting and assuming a new role, for which there are no obvious prerequisites following the 2020 Artsakh War.

The next concept is that of a small, non-aligned state. Non-alignment is a state policy of not joining any military alliance. It is important to distinguish it from policies of neutrality and hedging, because neutrality is not a guiding concept of a state’s foreign policy and is only employed in the event of war or conflict. With the hedging policy, the state adopts a non-interference strategy while not ruling out the possibility of joining any future alliance.

When discussing Armenia’s non-alliance status, it is important to remember one fundamental concept: non-alliance cannot be viewed as a goal, as it may lead to the state’s isolation from the outside world. Instead, it should be considered a means to create a mutually beneficial network of strategic partners while bypassing the systemic limitations that arise from being in an alliance. Additionally, non-alliance can be used to project political power and influence in cooperation with small states, serve the state interest of the Republic of Armenia in approaches arising from the characteristics of large and small states, ensure visibility of foreign policy, and become a regional actor.

If non-alignment is perceived as a means, Small State Specialization can become the driving force of foreign policy, because it specifies what Armenia can contribute to potential foreign partners while also formulating its expectations from them.

Adopting a non-aligned political stance and establishing systemic vectors of cooperation with different centers of power in the world can contribute to the effective implementation of a co-alignment strategy in foreign policy. This approach seeks to diversify Armenia’s international political environment by engaging significant partners, while reducing the dominance of one strategic partner and Armenia’s dependence on it. Implementing the co-alignment strategy could result in the formation of bilateral or trilateral strategic partnerships aimed at both regional (e.g. Armenia-Greece-Cyprus) and inter-regional (e.g. Uruguay-Armenia-Singapore) strategic agendas.

Azerbaijan is an excellent example of the benefits of non-aligned status. By considering non-alignment as a means, Azerbaijan has achieved maximum maneuverability in foreign affairs to promote its national security interests and establish strategic partnerships, even with Russia and Turkey, both of which approach their inter-state relations with a conflictual-cooperative logic. Consequently, Azerbaijan increased its political leverage in the exchanges between Russia and Turkey, and can also influence the latter’s policy in the South Caucasus with its own agendas. While Armenia strengthened the collective defense system of CTSO through its membership, Azerbaijan formed mutually beneficial strategic relations with all of Armenia’s CSTO allies.

When developing Armenia’s post-war national security strategies, the Small State Specialization Concept and Small Non-alliance State Concept can be complemented with other effective concepts. However, it is evident that Armenia cannot have a National Security Strategy without a solid conceptual foundation, as it would perpetuate more unsound policy.

CSTO: Closer to Azerbaijan Than Armenia, Part I

Armenian experts were hardly under the illusion that the CSTO would fulfill its statutory obligations toward Armenia, given strong military and political ties between Azerbaijan and some CSTO members.

Read moreAlso see

Abdication of Duty and the Art of Scapegoating

Russia is not simply abdicating its responsibilities towards Armenia; it is directly working against Armenia’s interests by aligning with Azerbaijan to strengthen the Russo-Azerbaijani axis and methodically discredit official Yerevan.

Read moreAutocratic Legalism and Azerbaijan’s Abuse of Territorial Integrity

Azerbaijan’s approach to the Nagorno-Karabakh issue is a perversion of the concept of territorial integrity. It makes a mockery of legalism and constitutionalism, hijacking the law and using it extra-legally to violate civil, civic and human rights.

Read moreWhy International Actors Are Responsible for Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh

If the international community fails to stop the genocide and ethnic cleansing of Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh, it will serve as a dangerous precedent for the international order and members of the UN Security Council, including the mediators, will be deemed responsible for it.

Read moreAll Armenian Men in Nagorno-Karabakh Are Now Targets for Arbitrary Detention

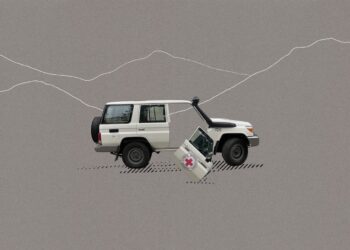

On July 29, Azerbaijani border services kidnapped and detained an elderly man who was being transferred from Artsakh to Armenia by the ICRC for medical treatment. Baku may now target and detain every male in Nagorno-Karabakh, writes Sossi Tatikyan.

Read moreWith Russian Inaction, Armenians Look for A New Ally

Russia's perceived unwillingness to assist Armenia and fulfill its treaty obligations during times of crisis has compelled both the Armenian government and the general public to seek new allies. France, the U.S., EU and Iran have emerged as potential frontrunners.

Read more

To be a non aligned state, a country needs three things 1) a strong economy and 2) a strong military, 3) strong leadership . It seems that these are the essential factors missing in Armenia. There has been a lot of discussion during the past 3 years whether Armenia should be part of Russia and CSTO or be aligned with the west. Actually Armenia could do either and still be in trouble. There is no substitute for Armenia standing up for itself militarily and economically. It seems that the Kocharyan/Sargsyan regimes not only aligned with Russia but more importantly let the economy and military stagnate. Now Armenia is paying the heavy price for that. Pashinyan has tried to revitalize the economy but has also made serious military and diplomatic blunders which may cancel each other out.