Armenia’s mining governance—namely, the decision-making process on granting mining licenses and monitoring performance and ensuring compliance with laws, standards, and contracts—is defective. These defects have resulted in critical failures, which have yielded dangerous economic, social and environmental losses for the country. The new government must assess the existing situation urgently and take determined steps to remedy the defects.

Very few mining companies in Armenia have been profitable. Analysis of economic data over a five-year period by a team of World Bank experts showed that “in fact loss making is a common pattern for the metal mining companies.”[1] Of a total of 14 operational mines in the period 2010-2014, eight had been running at a loss, most of these recording losses each individual year. “It appears that mining permits have been granted for unviable projects,” concludes the report.[2]

Referring to the prevalence of loss-making mining operations in Armenia, World Bank experts state that this failure is acutely significant “in the light that the last 7-8 years represent a period of historically high commodity prices.” Moreover, these losses were incurred even though mining operations in Armenia have nearly zero environmental costs. They state this latter point more mildly, saying “this poor economic performance has been happening at the same time as inadequate resources have been invested [by mining companies] in pollution prevention, and environmental management ….”[3]

This pattern of loss making and failed operations has continued. In 2017, out of the 28 metal mining license holders, seven were in operation and one mine, Amulsar, was under construction. Since then, another mine, Teghut, stopped operations in January of this year, bringing down the number of operating mines to six with Amulsar still in construction. Teghut was the second largest operating mine in Armenia.

These losses and closures have occurred even though Armenia has an adequate and average fiscal regime. Analysis by the AUA Center for Responsible Mining’s Mining Legislation Reform Initiative indicates that in Armenia the combined royalty and tax burden on mining companies is very reasonable, in fact average when compared to other countries with similar mining sector structure. [4] The World Bank assessment reaches a similar conclusion.

Despite this, in 2017, the Government of Armenia further relaxed the fiscal regime for mining operators. Before then, the Tax Code set a floor under the royalty value of minerals–the value used for calculating the royalty on metal sales–at 90% the London Metal Exchange (LME) price. Pegging minimum royalty value to the LME price is an important tool for managing transfer pricing risks on metal sales.

In 2017, however, the Government of Armenia made a further concession to mining companies by allowing the royalty values to be up to 20% lower than the LME price, in effect lowering the effective royalty rate, increasing transfer pricing risks, and allowing mining operators to transfer more of their costs to the state budget. Analyzing the rationale for this fiscal relaxation could be the subject of another discussion, but it should be considered as a core topic in the policy and governance of the sector.

If the financial failures were limited to one or two companies, the question of inadequate governance perhaps could not be posed as sharply as I intend here. The fact that financial failure has been pandemic compels us to seek the answer in the decision-making process to grant licenses to begin with. This is also a conclusion that the World Bank report reaches, recommending that Armenia adopt a mining policy that can filter out such projects.

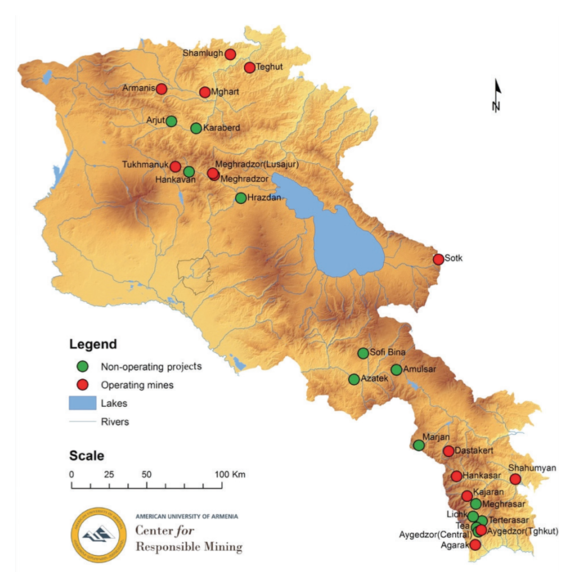

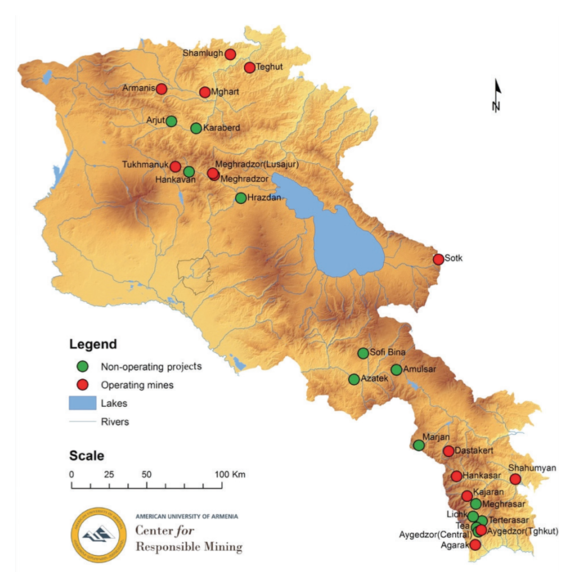

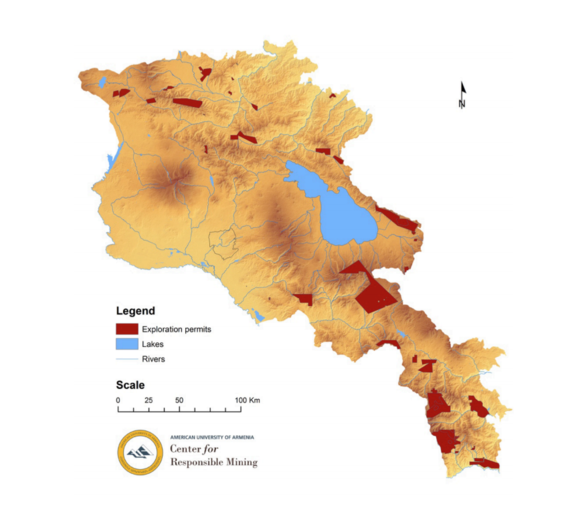

Metal mining projects in Armenia as per December 2015.

Now let’s focus our attention to one, and to date, largest of these failures, the Teghut mine. The mine is located in the northern Lori province, 25 km from the border with the Republic of Georgia. Despite 5-6 years of protests by environmental activists, Teghout CJSC, a subsidiary of the Lichtenstein-based Vallex Group, received a license to extract copper and molybdenum. According to the most recently updated terms of the license, the duration of the license is for 15 years (2013-2027).

While it was being planned and built, the mine was touted to have a closed-loop water recycling system, rainwater diversion canals, deforestation offsetting, and more. It’s PR blitz had young people marching in the streets of Yerevan wearing company t-shirts and waving company flags, convincing people that the mine will be an exemplar of sustainable mineral extraction the likes of which the region has never seen.

Significantly, in August 2013, PensionDanmark, the Danish retirement fund, agreed to make available DKK 350 million (about 62 million USD at the prevailing exchange rate of the time) through Denmark’s export credit fund, EKF. These funds were to enable the mining company, Teghout CJSC, to buy processing equipment from the Danish engineering company FLSmidth.[5]

The CEO of PensionDanmark, Torben Möger Pedersen, summarized the dual win of the project as “On the one hand, the partnership will ensure a return for our members well above the bond rate, and on the other hand it will help make more Danish export orders possible at a time when more traditional financing is difficult.”

In the same announcement, PensionDanmark states that the “financing agreement is conditional on the mining operations satisfying international environmental and safety requirements.” The CEO of EKF, Annette Eberhard, reiterated that the investment will ensure compliance with high international standards. She is quoted as saying “We’re naturally delighted to be able to enter into this agreement, which will increase Danish exports. And, what is more, for a project that is setting new standards for mining in Armenia. We have imposed a number of requirements, which will mean that the mine will be the first in Armenia to satisfy the international standards.”

Evidently, the mining operator allayed the investor’s concerns regarding compliance with “international environmental and safety requirements” as ultimately EKF committed the funds, Danish equipment was purchased, delivered to Armenia, and put to use with the mine starting to show production and revenues by 2015.

However, less than two years into operation, in October 2017, the EKF announced that it is withdrawing its funding from Teghut due to repeated violations of the terms of agreement and warnings. [6] In its press release EKF states that two critical shortcomings “formed part of its decision” to withdraw funding:

– The mine’s catchment basin has overflown into the adjacent area. EKF has on multiple occasions called attention to this problem.

– Despite multiple reprimands from EKF, the mine was unable to document that the dam complies with international standards.

They cite a third factor, which while not part of the mine, seems to have influenced the investor’s final decision to withdraw. The Teghut mine processes some of its copper ore at a smelter in the nearby city of Alaverdi. The smelter is owned by Vallex Group, the parent company that owns the mine. EKF stated that the occupational health and safety conditions at the smelter are completely unacceptable. On multiple occasions, it has pointed out “the deplorable conditions at the smelting works to the mining company and strongly urged the mining company to exert its influence to achieve better working conditions.” Evidently Teghout CJSC was unable to satisfy the investor also on this request.

We don’t know if these account for the entirety of the reasons as to why EKF decided to withdraw support. For instance, we don’t know if Teghout CSJC, the borrower, was making its loan payments on time and according to the terms of the agreement. What we do know now is that a mere three months later, in January of 2018, Vallex announced that it is indefinitely suspending operations at the Teghut mine, sending employment termination notices to 1032 workers. [7]

Vallex produced the following explanation, leaving some readers incredulous, some perplexed, and some concerned:

“At the present stage of its development … [Teghout CJSC] and its team are working on expanding its mineral processing capacity and operating efficiencies. This challenging task required the involvement of not only Armenian, but also internationally recognized engineering companies, who are currently conducting thorough research and engineering analyses. The result of this joint effort, by definition, is going to be a better, more feasible path forward from operational and technical perspectives. It will ensure the ability of Teghout to operate at the highest technological parameters for mineral processing.” [8]

Incredulous because there is no mention of the critical environmental concerns raised by EKF. Perplexed because the mine started operation only two years ago using state-of-the-art technologies imported from Denmark. So, what do they mean by “at the present stage of its development … expanding its mineral processing capacity and operating efficiencies” and “to operate at the highest technological parameters for mineral processing.” Isn’t this what $62 million of Danish investment bought?

And here is where some start getting concerned. Maybe the mine did not yield the reserves expected. So, maybe this is all a pretext to request for an expanded territory to mine (which in their mind translates to more uncontrolled assault on the environment). There have been no further statements from Vallex about the environmental concerns or the future of the mine.

Many questions arise when reviewing this brief account of Teghut’s rise and demise. Much discussion can and should be had on the benefits and harms of foreign investment under conditions of poor environmental and social governance. However, for my analysis here, the key question I’ll turn to is: Where were the state institutions in all of this?

Where was the state when Teghut was built, started operations, when EKF made its investment, and ultimately when EKF started sending warnings and ultimatums to the mining company? Where were the environmental inspections, occupational health and safety inspections, technical facilities approvals and inspections, and mine inspections to ensure compliance with the terms of the permit? In other words, how well did the state perform a part of its governance role with respect to the country’s second largest mine?

A strange but compelling segue to addressing our key question is that on March 21 of this year during a parliamentary hearing, the former Minister of Economic Development and Investment announced that the Teghut mine will restart operations in late 2018 or early 2019. This is indeed interesting as the announcement came not from Vallex but the state representative. The Minister’s announcement is made in a context where no state representative has made any comments on Teghut’s environmental, safety, contractual, or fiscal compliance concerns regarding the mine.

So, where was the state? It turns out that for a good portion of the time, key state governance functions were suspended. From August 2015 — December 2017, there was a moratorium on most inspections. The government’s publicly stated rationale for this was to remove obstacles to doing business. The only time mining and environmental inspectorates were engaged was when the tax inspectorate, activities of which were not suspended, asked them to accompany it on company visits.

While there were no planned inspections, the ministries and the relevant inspectorates, were obligated to investigate if well-grounded complaints were presented by citizens or organizations. The history of efforts by citizens and civil society organizations to get public authorities to perform their governance functions, particularly in the case of Teghut, has a decade-long history.

The story is densely packed with complaints filed with state agencies, lawsuits in courts with some cases ending up in the Republic’s Constitutional Court and some in international courts, as well as appeals to international bodies such as the Aarhus Compliance Committee in Geneva.

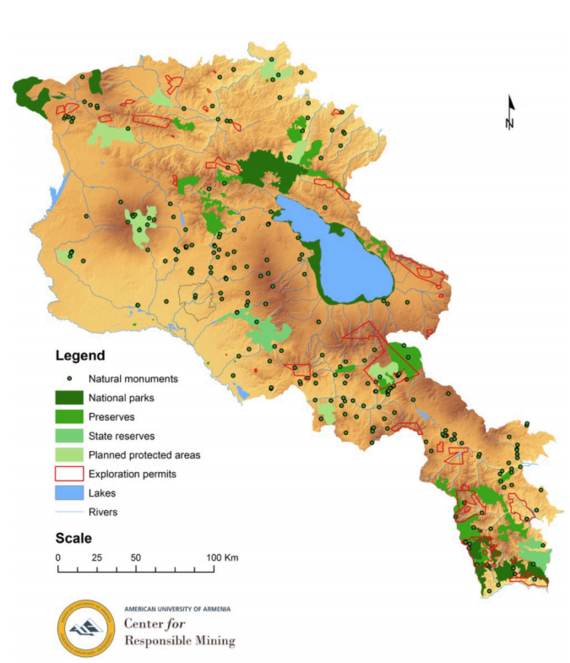

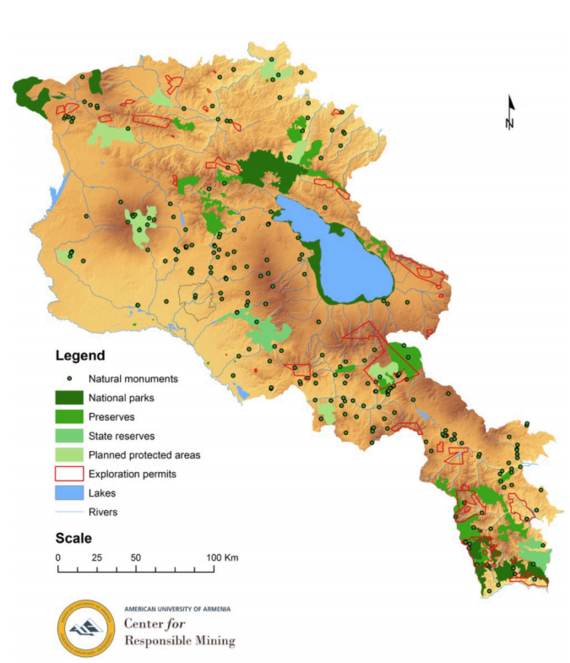

Protected areas of Armenia in relation to active exploration permits as per December 2015.

Some of these actions resulted in incremental progress but mostly there has been no outcome, with the Teghut mine remaining outside of state (and public) purview. Along with some of the residents of the Teghut and the nearby Shnogh villages, many civil society organizations worked to enable greater openness, accountability, and protection of the rights of citizens and the environment. The civic groups included the Save Teghut Civic Initiative, EcoDar NGO, Ecological Right NGO, Helsinki Citizens’ Assembly Vanadzor Office and Transparency International Anti-Corruption Center. It will require a massive tome to review and parse through all the actions, facts, steps, legal strategies and maneuvers, successes, and failures with regard to the Teghut mine. [9] To illustrate the governance failure, however, I will quickly review one of these actions by civil society aimed at compelling better state oversight and accountability.

On May 18, 2015, the Administrative Court of Armenia agreed to hear Case No. VD/1726/05/15 brought by the plaintiffs Susanna H. Shaxkyan, a resident of the Lori Province where the Teghut mine is located, and the Ecological Right NGO. The defendant in the case was the Republic of Armenia Ministry of Nature Protection. The plaintiffs demanded that the court oblige the defendant to carry out inspections at the Teghout CJSC and its mine.

The plaintiffs claimed that civil society groups have “irrefutable facts …, which showed that the mining company had substantially deviated from the conditions of the project approved ….” To continue to exploit the mine under the new conditions, the complaint argued that “the company needed to apply for a new permit while going through all the necessary steps and procedures, including all phases of public discussions. Those inspections were needed to identify the relevant violations and their consequences through a legally defined procedure.”

The court case was a culmination of years of efforts by civil society groups to get the Ministry of Nature Protection to conduct inspections, which, according to Ecological Right NGO, the latter refused to do citing various reasons, especially pointing out that the project is at its construction phase and it is not possible detect any deviations until operations commence. The efforts to compel the Ministry to conduct inspections (and their lack of progress on it) was documented in the Republic of Armenia’s Human Right Defender’s annual reports of 2013 and 2014. [10]

On July 1, 2015, a month and half after the court case was opened, the Ministry of Nature Protection presented a letter to the court that per Ministerial Decree No. 000115, issued several days prior, the appropriate inspection agencies were ordered to conduct an inspection of Teghout CJSC. This inspection was to be carried out between June 24 and August 4, 2015. At an August 24 court hearing, the Ministry of Nature Protection representative asked the presiding judge to dismiss the case since the Ministry is conducting inspections as demanded by the plaintiffs. As such, the Ministry argued, there is no longer a dispute between the parties.

In response, the plaintiffs’ attorney, Hayk Alumyan, petitioned to have the defendant produce additional evidence regarding the course of the inspection. The defendant argued that the ministerial decree is sufficient evidence and reiterated the request to have the case dismissed. The judge agreed with the defendant and the case was dismissed on August 25, 2015. The judge ordered the Ministry to reimburse the 8000 AMD (about 15 USD) court fees paid by the plaintiffs.

Parallel to all of this, on July 30, 2015—four days prior to the August 4 deadline of the inspection of Teghout CJSC ordered by the Minister of Nature Protection, the Government of Armenia passed a resolution ordering most inspections other than tax and customs to be suspended starting on August 1 for a 5-month period. The moratorium was thereafter extended every six months until the last extension ended in December 2017. According to the court summary document, the Ministry representatives at the hearing did not mention this new resolution and any impact it may have on the already ordered inspection.

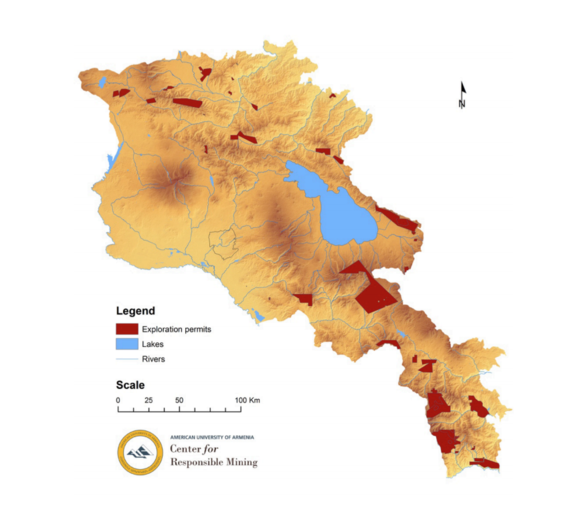

Exploration permits for metallic minerals as per 1 December 2015.

A month after the court case was dismissed, in a letter dated September 28, 2015, the Ecological Right NGO (plaintiff in the now closed case) wrote to Ministry of Nature Protection requesting it to produce the results of the inspection that was ordered by the Ministry of Nature Protection. On October 10, 2015, the Ministry of Nature Protection, in a letter numbered 5/23/54059, responded that the results of the inspection cannot be released as the initiated inspection has to be completed according to order and procedures set forth by law and once completed the results will be issued in an official report.

Ecological Right NGO waited. With all inspection moratoriums ending in December 2017, in February of 2018 the NGO wrote to Ministry of Nature Protection requesting that it produce the final report on the Teghout CJSC inspection. In a response letter dated February 23, 2018, the Ministry forwarded a February 20 letter from the Inspectorate stating that in fact no inspections were ever initiated and carried out on the Teghout CJSC by the Ministry of Nature Protection! Stunned and angered by this response, in a news article, the Ecological Right NGO director is quoted as saying that “This implies that the court was deceived [by the RA Ministry of Nature Protection]. With this newly emerged evidence, we will be going to the court again, demanding that inspection at Teghout CJSC take place.”

The impression from all of this is that the ministry, the government, and the court are performing a well coordinated theatrics, stymieing efforts by citizens and civil society to compel the state to perform its basic governance functions with regard to a project that had (has) significant social, environmental, and economic impact on the region and the country. The bitter irony in all of this is that the state claimed to have done this under the guise of economic development, a result which it also miserably failed to achieve in Teghut.

Of course, the account presented above is the story of one civil society organization pursuing the government to perform its governance role with respect to one mining project. Grave governance failures have been pandemic in Armenia. To name only a few:

– Tailings from the Agarak mine in the Syunik region have been discharged into open canals that lead into the Arax River. The state has been unable to stop this. The same mine has closed tailings sites that are not capped and the dried tailings dust blows to the nearby city of Agarak and its agricultural land. The same mine operator has a tailing pond, the pipes of which had significant leakages when visited in 2016.

– The Kajaran mine in Syunik moves its tailings 30 km to its Kapan tailing site, Arstvanik, using massive amounts of water. Such massive use of water resources has to be reduced and the tailings management practices brought to international standards. Furthermore, and shockingly, the tailing pond water is released untreated into the Okhtar River which soon after flows into the Voghji River.

– The nearby non-operating Kavart mine, a territory that was part of the Kapan gold mine and which was was separated from the productive part of the mine by its previous owner and clearly with the complicity of the state, represents one of the worst sources of acid rock drainage pollution in Armenia. The state has taken no action to manage and remedy this. Complaints by local communities have been met with a series of all too familiar circumlocutions and run arounds.

– Activist groups have produced studies and raised questions about the Amulsar mine and its acid rock drainage risks. The state has either lacked the will or the legal mechanisms to review and consider these studies. Is it that the state really believes in the capacities of its environmental impact expertise and is confident that all risks were adequately revealed and addressed during the EIA? Is the state unable to address its past technical and policy deficits for a project that could have long term, significant impact on a highly sensitive part of the country? Doesn’t the law allow for consideration of new facts and evidence as they emerge?

– The Akhtala mine in the Lori region has been a significant source of pollution risk for nearby communities. It has also allowed tailing water to drain directly into the Debed River. The state has taken no effective action to prevent the company from continuing to pollute.