I once read somewhere that the contours of the magnitude of trauma define the outline of the future.

1915 outlined that story, extending like the moving images of an echocardiogram, for many of our personal family stories and in the collective national memory.

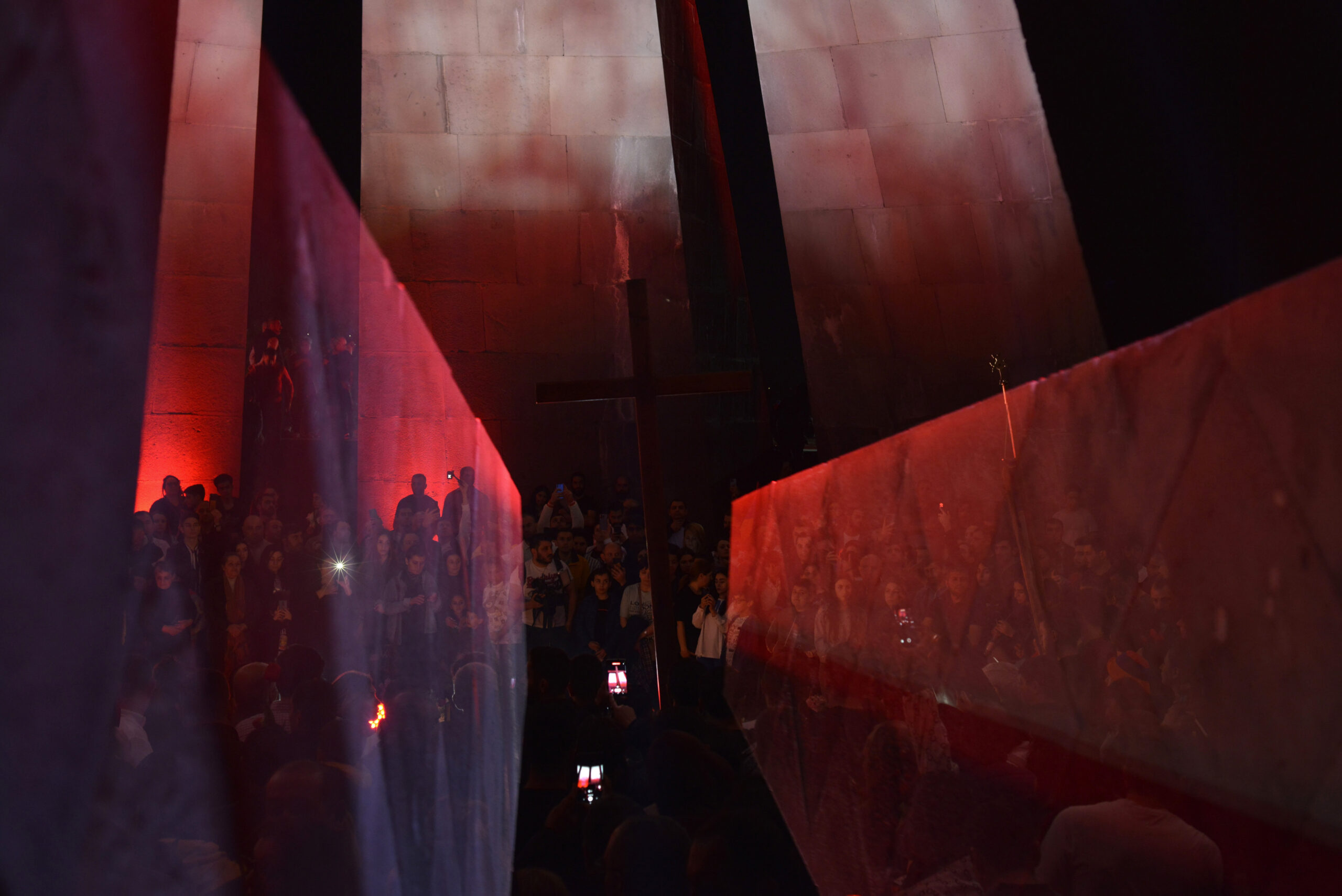

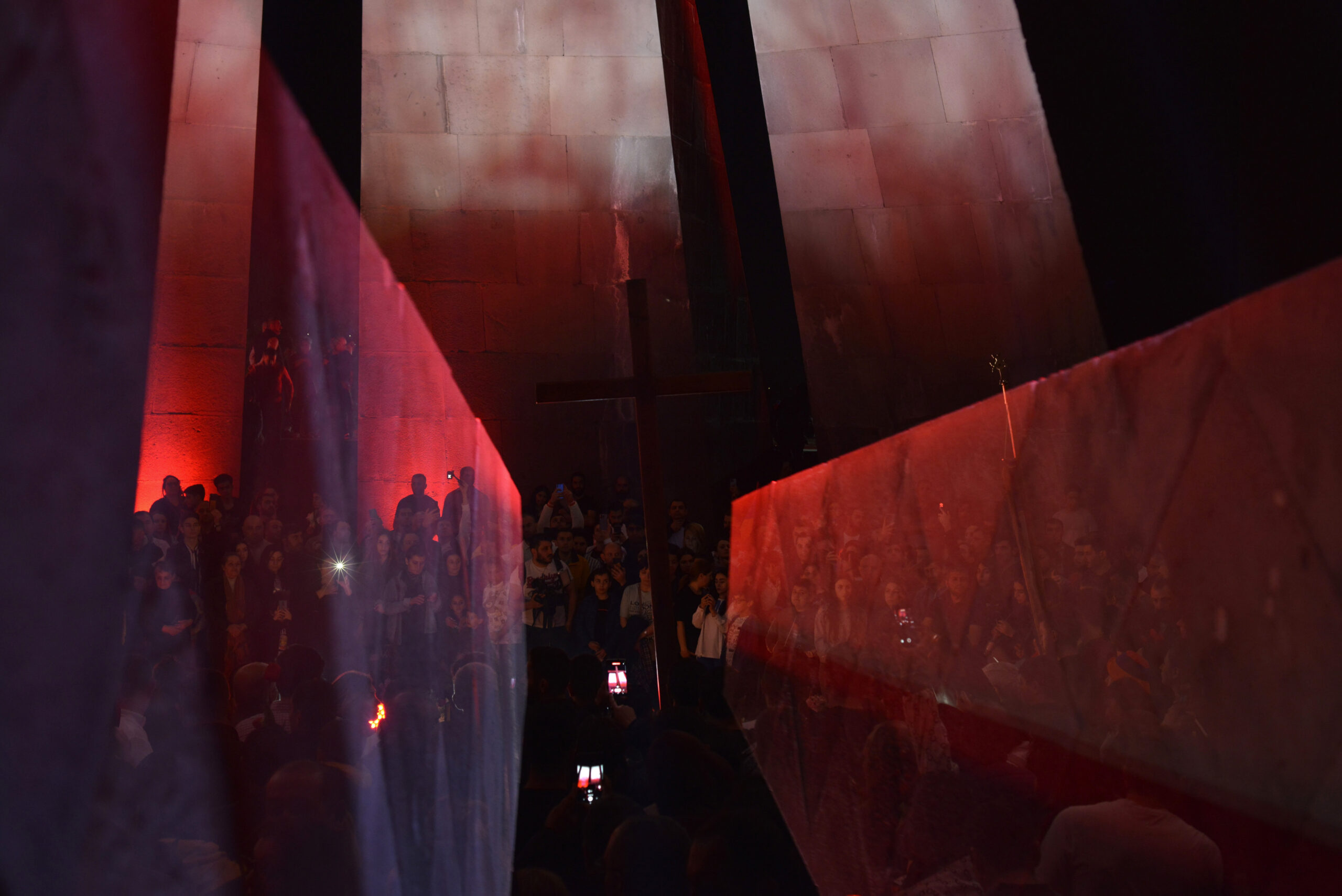

I live in Ajapnyak. Tsitsernakaberd is close by; you can see its soaring height from the street.

The crowded procession that passes by my neighborhood on April 24, is an annual reality that I have grown up with since childhood.

I rarely go to Tsitsernakaberd on that day. I’m there more often on other days, when the grounds of Tsitsernakaberd are mostly empty, and there is silence near the eternal flame, where one can be quiet with that past for which the monument was built. The story of Mukuch, my mother’s stepfather, is my family history’s link to 1915.

I barely remember my grandfather Mukuch; just a few episodes of how he mixed a barrel full of grapes and how he dug his garden. My grandfather didn’t speak much. My mother would tell the story of Mukuch that she had heard as a child. Mukuch had five siblings. The Turks kidnapped his oldest sister, and killed the rest in front of his eyes when he was 13 years old. His mother, seeing the slaughter of her children, died of a heart attack. My grandfather was saved by hiding in a pile of corpses – advice given to him by his Turkish neighbor. He somehow made it to Tehran, where he lived, and got married. He adopted my mother in 1946 and came to Yerevan with the hopes of having a better life.

He built a house in the third Massif (a suburb of Yerevan), cultivated a garden, and went to work at a printing house. Each year he would travel to Sukhumi, to meet with cousins he had discovered; that is where he died.

My personal connection to the Genocide is the story of my step-grandfather. My hope, that his photos in our family album would complete the fragments of my memory, was in vain.

The Fortress of Swallows (Tsitsernakaberd), from where swallows, according to legend, delivered messages by Astghik, the Armenian goddess of love and water to her lover, Vahagn the god of fire, thunder and war, is a myth that is mixed in with the memory of my childhood, where Mukuch is silent and digging in his garden.

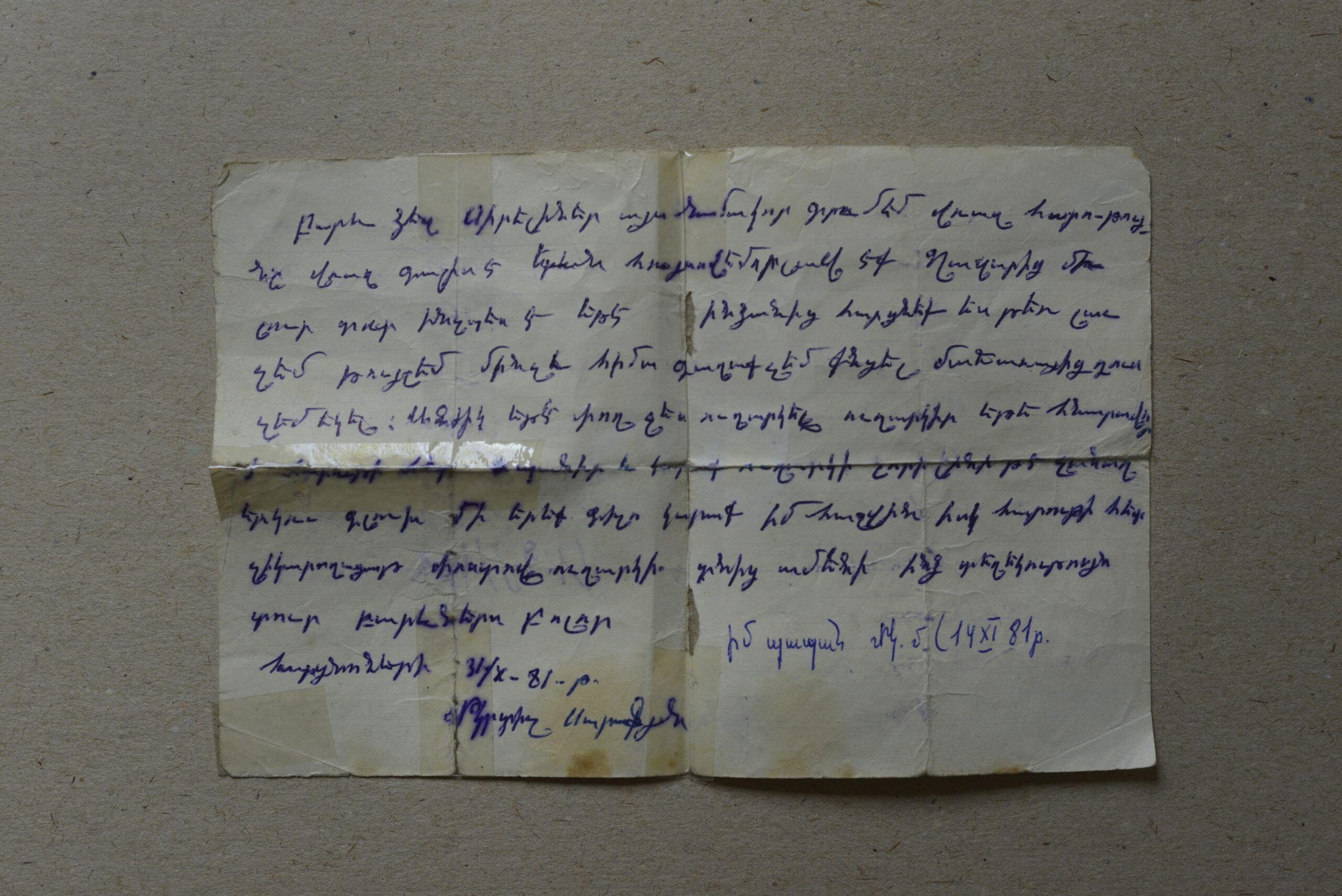

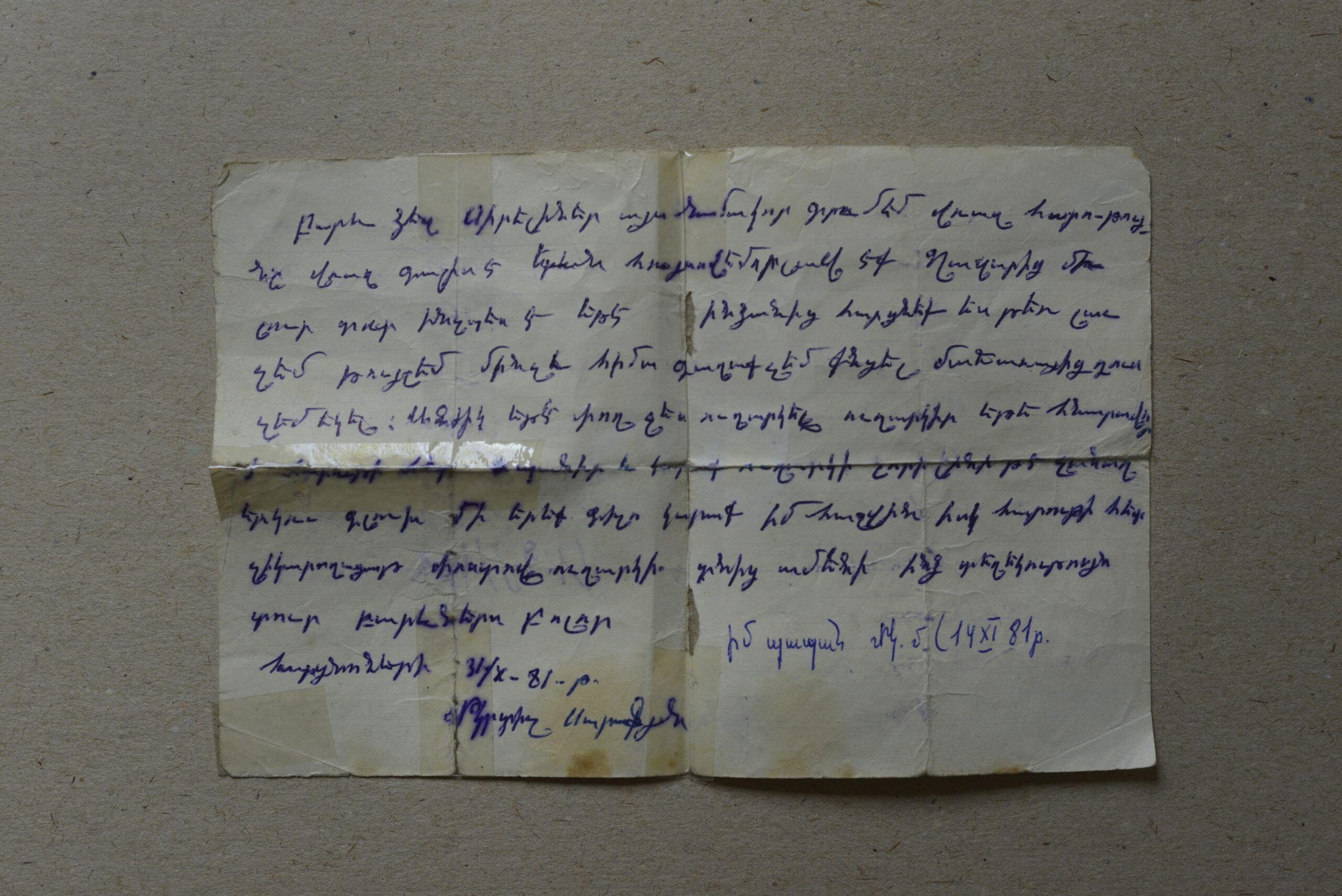

Captions for the images from the author’s family archive (right side)

Dear Vaghinak,

Thank you for sharing your personal and family experiences about the Genocide. I recall my grandmother telling a similar story of how she and her younger sister and brother managed to hide in a similar manner, thinking that no one would look for them in such a place. They were eventually rescued and brought to an orphanage in Beirut. It still astounds me that they could survive and escape the nightmare of those times.

With best regards,

Paul