“After undergoing tests while pregnant a year ago, I found out I had HIV,” 28-year-old Varduhi, whose name has been changed, remembers. “From that moment, problems began. At the Avan branch of the National Center for Infectious Diseases, the doctor was so rude to me; so disdainful. He told my parents: ‘Go, find out where your daughter has been fooling around.’”

After her diagnosis, her husband also got tested. He already had AIDS. Varduhi says she was infected by her husband, who would often go abroad for work and, presumably, was infected there.

The news about the disease and her doctor’s attitude caused psychological distress for the pregnant Varduhi, which she had difficulty dealing with.

She had her baby at the Research Center of Maternal and Child Health Protection, where the doctor was caring but the nurse’s behavior and attitude was unkind.

“I had just had my baby and was still in pain when I heard one of the nurses urging the others to stay away from me as much as possible,” says Varduhi. “Then, when a nurse came to give me an injection, she stood far away and did her work very quickly, as if I would have infected her airborne. I couldn’t stand it and I told her she shouldn’t treat me that way, no one is immune from diseases.”

Despite her unpleasant experience, Varuhi says that thanks to her doctors’ skill, it was possible to prevent the transmission of HIV from her to her baby.

Don’t Let Anybody Find Out

Only their parents know that Varduhi and her husband have HIV. Varduhi says that they are careful that no one finds out. They’re worried that if the information gets out that she and her husband will face discrimination. Only when visiting medical facilities do they warn medical staff that they have HIV.

Urologist Haykaz Harutyunyan, who has treated and operated on patients with HIV and many other infectious diseases, notices that patients sometimes inform doctors that they have HIV with fear, perhaps expecting that they will face discrimination. According to Harutyunyan, however, a doctor should always be conscious of the mission they have undertaken.

“Once I was examining a patient and he reminded me that he has HIV. I told him that I was aware. He said he was surprised that despite knowing about his disease I was still standing so close to him,” Harutyunyan recalls. “He had faced discrimination in the past and receiving normal treatment shocked him. I use the word ‘normal’ here because I believe that no patient with an infectious disease should receive treatment differently and not even in special and exclusive treatment in a positive way, because this causes patients to tense up.” He stresses that when interacting with patients with infectious diseases, medical staff must treat them the same as they would others.

Harutyunyan, naturally, is aware that society treats people with infectious diseases in a prejudiced manner. He believes it’s because people don’t have enough information about these diseases and how they are transmitted.

Davit, whose name has been changed, is a 35-year-old man who lives in Armenia. He found out he had HIV a year ago when he went for an examination because of lung problems. Prior to his diagnosis, he had gone abroad to work, which is where he thinks he got infected. Learning about his disease has led to psychological difficulties. He has only told his sister about his diagnosis. He hasn’t told his mother to save her from the grief. When he told his girlfriend about the illness, she immediately broke off the relationship and even stopped talking to him on the phone.

“Of course, I understood her decision to end our relationship, but I can’t understand how she could have stopped it so abruptly,” admits Davit. “I know how badly society treats people with HIV. That’s why I haven’t told anyone about my illness — not an acquaintance, friend, or neighbor. I only tell medical staff.”

If You Have an Infectious Disease, We Can’t Operate on You

Davit says that he has yearly checkups at the National Center for Infectious Diseases and he takes medication once a day. He follows the advice doctors give him and is now living as he did before when he didn’t have HIV. David admits that while there are no problems when it comes to HIV treatment, which is free and available and specialists don’t discriminate, when going to other medical centers however, he is often denied medical care. Encountering discrimination is inevitable. Davit has a problem with his nasal septum, it is difficult for him to breathe and has headaches. He needs surgery, but he says doctors refuse to operate.

“I visited a hospital in Yerevan where the doctor examined me and scheduled a day for the surgery, but when I told him that I have HIV, his attitude and tone immediately changed,” says Davit. “He went to his office, consulted with other doctors, came back, and said that no one will operate on me. I went to another hospital and they also refused to operate on me.”

Ani, 48, who wishes to remain anonymous, found out in 2019 that she has Hepatitis C. Her husband also has the disease. She thinks she might have been infected at a dental clinic she used to regularly visit during or she got it from her husband. She found out about her condition when she was preparing to have surgery for uterine fibroids. After learning about her illness, the head of the given department at the hospital called her into his office and said: “We cannot operate on you. By the time we disinfect the operating room after your surgery, another patient might die in the meantime and we will have problems.”

Ani went to the Real World – Real People NGO, whose representatives accompanied her to the hospital to help protect her rights.

“At first, the doctor said they would operate. Then he went into an office with other doctors and when they came out, they said that they could not,” she says. “I’m sure it was because I had Hepatitis C. They did not give any reasonable explanation for not operating on me. The doctors and nurses — essentially everyone who knew that I had Hepatitis C — treated me very badly.” She also says that afterward she was in such distress that she refused to go to another hospital, started self-medicating, and is still not ready to go see a doctor.

Ani says that when she went to a polyclinic, they even refused to take her blood pressure when they found out she had Hepatitis C.

Even after her poor treatment at these clinics, Ani did not file a complaint, fearing that if she spoke up, more people would know about her illness. She was afraid that her children might also face discrimination.

“At these medical centers, I said, ‘You are doctors, you know better than me how one gets infected — why do you treat me so badly?’” Ani recalls, adding that after these incidents, she told only her mother and sister about her diagnosis. She says that her mother was worried but didn’t treat her badly. She had to tell her sister, because she had to borrow money from her for treatment. However, her sister, in an accusatory way, rudely demanded to know how she got infected.

“Then my closest neighbor asked me why I didn’t have my surgery,” says Ani. “Trusting her, I told her what happened. She said: ‘I won’t come to your house again. If my children find out, they will not forgive me. It’s dangerous, maybe my children will get infected too.’ I was shocked by her attitude.”

Discrimination and the Law

According to Article 14 of the Law “On Medical Care and Services for the Population,” “every person (a patient) has the right to be treated with care, non-discrimination and respect when receiving medical care and services.” Article 31 of the same law states: “Medical workers are obligated to show a caring, non-discriminatory and respectful approach towards the patient.”

Medical workers’ rights are stipulated in Article 30 of the same law which, however, does not include any clause about refusing to perform a medical intervention.

Secretary General of the Ministry of Health Vardanush Grigoryan says that medical staff are trained regularly. This training aims to increase awareness and eliminate discrimination and the 2022-2026 Action Plan for Combating HIV/AIDS includes measures to combat discrimination.

Grigoryan says that complaints made by patients to the Ministry about their medical care are not registered based on the diseases they have. However, she assures that solutions have been provided for every case of discrimination against people with HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, Hepatitis B or C, or other diseases when that information has been available.

“In order to provide a systematic solution to this problem, a working group has been created by the Ministry of Health which will develop tools for monitoring and overseeing discrimination cases and issues related to personal data privacy of patients,” says Grigoryan. “Meanwhile the ‘Community Engagement, Human Rights, Gender Equality’ working group works alongside the Measures Against HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria in Armenia Coordinating Committee.”

People with infectious diseases, specifically those with Hepatitis, HIV/AIDS, and tuberculosis, face discrimination. These diseases are included in a list of diseases that pose a threat to the public.

According to Article 19 of the Law “On Medical Care and Services for the Population,” a person with a disease that poses a threat to the public has the right to receive medical care and services free of charge at medical centers that have a license for providing corresponding treatments.

Specialized medical care and services for HIV/AIDS are set up at the National Center for Infectious Diseases and are free. Treatment of acute viral hepatitis is carried out with state assistance for diseases and conditions that require urgent medical care. When diagnosed with chronic viral hepatitis, medical care and services for those who are socially vulnerable is provided free of charge, with the exclusion of antiviral treatment.

The Real World – Real People NGO was founded in 2003 by a group of doctors and people with HIV to improve the quality of life for those living with HIV. The NGO records cases of discrimination against people living with HIV, both within state and public sectors.

Zhenya Mayilyan who heads the NGO says that people with infectious diseases in Armenia still face discrimination when receiving medical care and within social spheres. This is why people avoid letting others know about their diagnosis; even if they’re not worried about themselves, they worry about their family members and children.

According to Mayilyan, sometimes women infected by their husbands are discriminated against by the husband himself or his family members.

“There are women who discover they have HIV when they have routine tests done during pregnancy,” explains Mayilyan. “It is then recommended that their husbands or sexual partners also be tested. Sometimes when a woman is the first one diagnosed with HIV, she is discriminated against by the family. Family members say, ‘You are to blame, you brought the infection.’ Despite the fact that afterward, when the husband is tested and it becomes clear that it was he who was infected before the wife, however, the blame is still placed on the wife.”

However, according to Mayilyan, the worst is when a woman is forbidden to go to the doctor or is hindered from seeking medical treatment.

“In our work, there have been cases when we learned that family members weren’t allowing or were preventing women from going to have tests done and get medication,” says Mayilyan. “One of the women we worked with who was diagnosed several years ago [with an infectious disease] together with her child, had not seen the doctor for a long time and hadn’t received the medicine they both needed. One of our specialists found out that they were living with a relative of her husband, and on whom they depended financially and they couldn’t visit the doctor without her consent. This woman did not believe that her relatives could have such a disease and prevented them from going to the doctor. Of course, after some work, we were able to get the woman and her child the proper treatment.”

Mayilyan states that, in general, legal awareness is quite low among Armenian society. Even people with infectious diseases often don’t know about their rights themselves. That is why the NGO also works on raising awareness. According to Mayilyan, the NGO is usually able to help citizens facing discrimination to eventually receive proper medical care. However, when they urge those citizens to file a complaint to the relevant authorities, many refuse, not wanting to have their condition known.

“The NGO prepares reports and sends them to institutions fighting against discrimination,” says Mayilyan. She emphasizes that if Armenia had a law on discrimination, the situation would be much better.

Statistics

According to the Ministry of Health, from 1988-2022, 4,979 cases of HIV infection were registered in Armenia, of which 3,466 were male and 1,513 were female; 51% of registered cases indicated that the place of infection was outside Armenia.

As of September 30, 2022, the number of people living with HIV in Armenia is 3,888, including 2,588 males and 1,300 females. The number of minors who are HIV positive is 56.

In 2020, the highest number of HIV cases was registered in Lori region and in 2021 it was in Shirak province. As of the third quarter of 2022, the highest number of HIV cases was registered in Gegharkunik region.

From 1988 to 2022, 2,387 patients were diagnosed with AIDS in Armenia, of which 1,772 were male and 615 were female.

As of September 30, 2022, the number of patients living with AIDS is 1,586, of which 1,122 are male and 464 are female. The number of minors diagnosed with AIDS is 30.

As of November 9, 2022, there are 332 registered patients who are receiving treatment for tuberculosis in Armenia, of which 261 are male and 71 are female. The number of children aged 0-14 that are diagnosed with tuberculosis and are receiving treatment is 12.

Also see

Unwanted: Why Is Abortion Still the Main Form of Family Planning in Armenia?

Abortion continues to be the primary measure of fertility regulation in Armenia and despite efforts to decrease the number of sex-selective abortions, these issues remain prevalent in the country. Sona Martirosyan explains.

Read more“Let Me Take Your Pain”: Palliative Care in Armenia

The Palliative Care Center steps in when conventional medicine stops working and the body does not respond to therapy. Gayane Mkrtchyan looks at the state of palliative care in Armenia, its challenges and prospects.

Read moreUnderstanding Postpartum Depression

Having a baby is the most joyous time in a woman’s life. The experience triggers powerful emotions and in some cases, can lead to postpartum depression. Gohar Abrahamyan provides valuable insights through her own personal journey.

Read moreIll and in Anticipation of a Miracle in Germany, Part 2

Armenians, desperate for life-saving medical treatment, travel to Germany with hopes and great expectations. However, sometimes, those hopes remain unfulfilled.

Read moreIll and in Anticipation of a Miracle in Germany, Part 1

Refugees have been living in a Düsseldorf's shelter for years, receiving treatment and waiting to either fully recover or be deported. In this series of articles, Armenians reveal how they arrived in Germany in anticipation of a miracle.

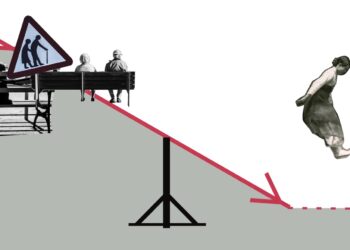

Read moreArmenia in Demographic Crisis

Recent data warns of a demographic crisis in Armenia. In a country with a high rate of aging, programs are being implemented to boost birth rates. But are they effective?

Read moreCatching Cancer in Time

The case for early detection of cancer and shifting cultural attitudes toward seeking medical treatment in Armenia.

Read moreObstetric Violence: Hidden in Silence

Many women are subjected to obstetric violence, which not only violates their right to receive dignified and respectful health care but can also seriously threaten their life and health.

Read more