Siranush Zarifian, pen name Siran Seza (1903-1973)

Siranush was born in Constantinople and after completing her studies at the American College for Girls, she left for Beirut and then later traveled to New York City. She enrolled at Columbia University to pursue a Master’s degree in literature. She published seven books, including a collection of short stories and her memoirs. Her short stories appeared in Diasporan Armenian newspapers such as “Hairenik” and “Nayiri.” In 1932, she founded the feminist journal “The Young Armenian Women” in Beirut, Lebanon. With this journal Zarifian wanted to bring Armenians into the global conversation on women’s right issue.

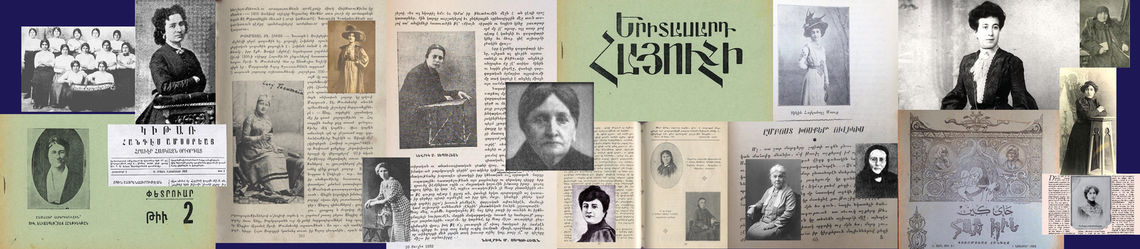

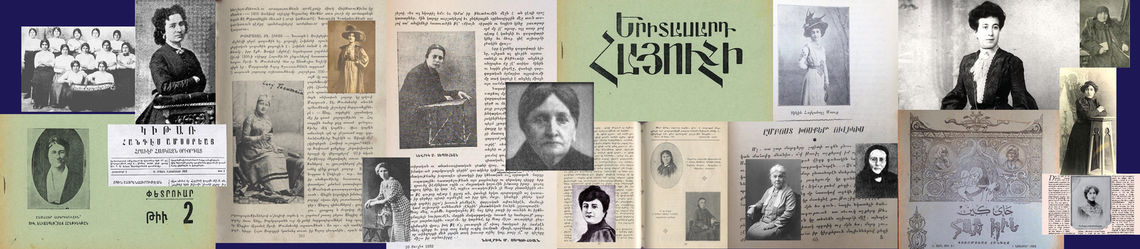

Elbis Gesaratsyan (1830-1910)

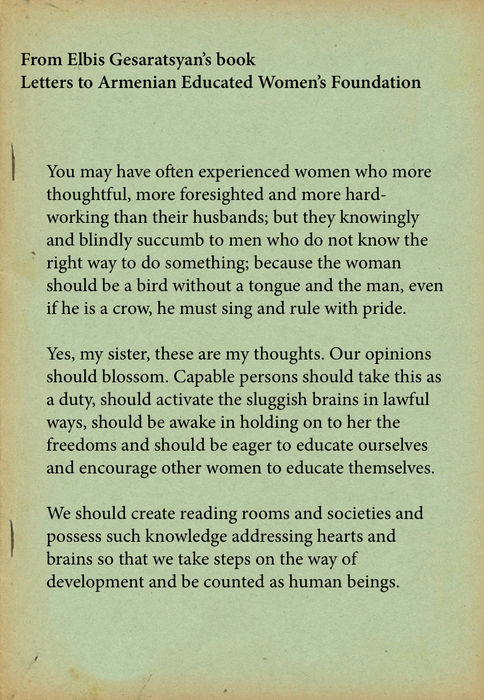

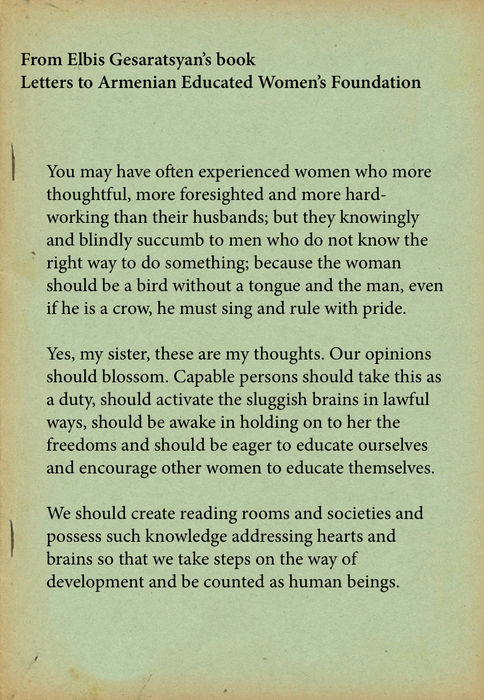

Gesaratsian is considered to be the first Armenian woman editor. She published Guitar, the first magazine for women in the Armenian language. In Guitar, Elbis wrote articles with the pseudonym “Yelbis Garabedyan” about the role of women in the community and about the education of women. She wrote four articles in the first issue of Guitar entitled, “The Spirit of Patriotism,” “To Young Girls,” “Service to Community,” and “Using Rights is Not insolent.” In 1879 she published a book titled Namagani ar Yntertsaser Hayuhis (Letters to Armenian Educated Women’s Foundation) where she wrote on female issues of education and sexual discrimination.

Avagyan says that students are told which author to read. “We can’t find out for ourselves who we are really interested to read until we are guided in a very systematic way, a system that really values already accredited male authors, and a system where women’s voices are not really heard that much.”

So how can we change the situation? Do we even need a change?

It all lies on the shoulders of the readers. Avagyan says that we should ask questions about women writers to librarians, to teachers and professors. If there is a demand, then surely more and more publishing houses would be willing to publish books of Armenian women writers, and editors might consider adding women writers in the textbooks.

“In a system where masculinity is valued more, the feminine production becomes secondary, and it becomes really difficult when you have secondary position to make your production important,” Avagyan says. “There have to be people around you who will make meaning of your text, who will write about it, who may be willing to translate it and to talk about it. There is always someone else who has to create value around what you have produced.”

Contemporary picture

While there are more Armenian women writers today thanks to the accessibility of education, they still remain on the periphery. Contemporary writers, both men and women struggle to occupy a space because the profession is not appreciated. Avagyan notes, “human beings don’t appreciate contemporary moments.”

Hambardzumyan believes that writers, in general, are not valued in Armenia: “A book needs to be viewed as an important source of knowledge, information and delight, then as an intellectual product, which is to be highly valued.”

Aslibekyan says that the dominant attitude in society regarding writers is of indifference. She says contemporary literature must be valued and there needs to be interaction with writers. “There should be regular meetings with contemporary writers, at schools, at universities, at book fairs etc.,” she says.

Students are not given the opportunity to interact with writers and educators are not compelled to move beyond the mandatory textbooks they use in their classes. In these circumstances, fostering curiosity and interest in contemporary writers is not on their agenda. And in this reality, who thinks of women writers?

While the literary works of women from the last century struggle to be heard, contemporary writers struggle to be read.

*In this article, the following textbooks have been mentioned:

Armenian Literature 7(2016), 8(2012), 9(2011) authored by Davit Gasparyan,

Armenian Literature 10(2009) authored by Henrik Bakhchinyan, Sergey Sarinyan, Edited by Vazgen Gabrielyan

Armenian Literature 11(2010) 12(2011) authored by Davit Gasparyan and Jenya Kalantaryan, Edited by Vazgen Gabrielyan