The burden of being a burgeoning democracy within an authoritarian orbit is a difficult geopolitical condition. More so, the burden of being a small nation, surrounded by aggressive and genocidal neighbors, is an existentially suffocating condition. Yet the collective burden of being a small, nascent democracy that is not only threatened by its irredentist neighbors, but must also suffer the fallout from the conflict of greater powers, is an impossible condition. The Russo-Ukraine conflict has not only made Armenia’s condition as a threatened small state more complicated, it has also increased the risk-propensity for the country both diplomatically and militarily. This impossible condition is exacerbated by the fact that Armenia has absolutely nothing to do with these developments, nor does it have any agency in producing even the smallest of effects on the outcome. This is the situation that Armenia finds itself in as a result of the Russo-Ukraine conflict: it has almost nothing to gain, yet has almost everything to lose.

What should Armenia’s policies be in confronting these developments, and how can Armenia mitigate any potential losses from the fallout of this regional war? The solutions are two-fold: a policy of “strategic shirking” and anticipating the weakening of Russia.

The Ukraine War has placed Armenia in an insuperable position, and the idiom of being between the Scylla and Charybdis does not do full justice in appreciating the extraordinary difficulty that the country finds itself in. The growing cleavages between the West and Russia is producing exuberant pressure upon Armenia’s ability to not fall into the trap of choosing sides. Yet escaping this trap invites a cluster of more traps and complex outcomes. How can Armenia bypass the problem of being trapped, yet do so without producing harmful residual effects? It must articulate a policy of “strategic shirking,” and so far, it has done a commendable job in utilizing certain tenets of this concept.

The Policy of Strategic Shirking

Strategic shirking[1] postulates that a certain degree of diffusion of power is taking place within a given region, and the process of this dispersion entails intense conflict and war. This dispersion in regional power shapes the behavior and interests of the lesser powers within the region, and those actors that subscribe to strategic shirking prefer that the declining hegemon bear the costs of this decline. Tensions rise when the declining hegemon expects partner or allied actors to assume the role of supporter, while the allied actor(s) attempts to shirk from offering such forms of support. Shirking behavior, to this end, is not defined by “strategic silence” or “balanced neutrality.” None of these concepts are tenable or consistently attainable within the post-Soviet space, and more specifically, during this current regional conflict. There are states that are tacitly supporting Ukraine and states that are tacitly supporting Russia. The one state within the region that deviates from this posturing is Armenia, for understanding the inapplicability of “silence” or “neutrality,” and noting the impossible position that it finds itself in, Armenia has selected to utilize the policy of “strategic shirking.”

Fundamentally, Armenia’s strategic position is to shirk from any entanglement. This is more nuanced than merely claiming neutrality, and it stipulates a modality of policies and actions that enhance the art of avoidance, that is, to shirk from any responsibilities, interactions, attachments, or involvements that have anything to do with the Russo-Ukraine conflict. Thus, strategic shirking, for example, does not entail Armenia distancing itself from Russia, as an actor, or from Ukraine as an actor. Rather, strategic shirking entails that Armenia, unequivocally, distances itself from the conflict. In more analogous terms, if there is an “elephant in the room,” the underlying objective of strategic shirking is to make every concerted effort, and to do so successfully, that the elephant in the room is not “addressed.”

Armenia, so far, has done an admirable job of implementing components of strategic shirking by developing pragmatically vague postures and a subtle language of cooperation and reconciliation, while refraining from directly engaging or tackling the actual nature of the conflict. Is this policy sustainable? Of course not. But it is not designed to be long-term. Rather, strategic shirking is specifically designed to be ephemeral in dealing with a temporary crisis. It is a policy of avoiding involvement in the present, but planning for the consequences of the future.

How can Armenia justify its policy of strategic shirking? It doesn’t need to, for everyone concedes that Armenia is a “geopolitical hostage.” In this context, as the intensification of the cleavages between the West and Russia places Armenia in an impossible position, shirking allows Armenia to “deny” these cleavages and avoid direct entanglement. Where shirking becomes no longer possible, Armenia may assume the posture of geopolitical hostage, thus allowing itself plausible deniability for being pressured into actions over which it has no agency. In the face of external pressure from Russia, for example, Armenia’s internal options become secondary, and Armenia loses agency in conducting its own foreign policy within this specific domain. More specifically, it is expected that as Russian military, diplomatic, and economic losses increase, Russia will intensify pressure in its sphere of influence and demand loyalty from states within its orbit, thus requiring Armenia, and other CSTO and Eurasian Economic Union countries, to vote with Russia on international platforms and to partake in Russian initiatives. While maximum shirking may not be possible within such circumstances, minimal shirking may be utilized. But most importantly, the fact that loss of agency becomes recognized by relevant international actors, this loss of agency allows for plausible deniability. Hence the concept of Armenia as “geopolitical hostage.”

The Leviathan Weakens

Deep trend analysis as well as quantified results demonstrate an observable and relative decline of Russian power due to the war in Ukraine. This does not suggest that Russia will no longer be the regional hegemon, but rather, Russia will be a less powerful hegemon. Collectively, Russia will come out weaker from this conflict, regardless of how the conflict concludes, than it did when it entered the conflict. This relative decline is qualified by basic metrics of measuring hard power: military capabilities, military spending, GDP (including GDP per capita), percentage of GDP spent on defense, heavy industry, research and development spending, and population trends. Even when utilizing the traditional Composite Index of National Capability (CINC), and quantifying the results based on the Correlates of War database, Russia’s hard power capabilities exponentially decrease. Thus, as an empirical referent, post-war Russia will be a much weaker actor than pre-war Russia.

This is good for Armenia. Not because we want to see a weak Russia, but rather, because the behavior and policies of a weaker Russia remain robustly pro-Armenian when compared to a stronger Russia. The geopolitical considerations of Russia’s weakening, based on systematized content analysis and geostrategic analysis, are qualitatively beneficial for Armenia. While this may appear counterintuitive, the findings, however, do support this conclusion.

The identification of trends that systematically provide a framework of patterns in understanding Russia’s behavior towards Armenia is prevalent in a dyadic model: Russia-as-secure-actor and Russia-as-insecure-actor. A weaker, and thus a less secure Russia, behaves towards Armenia as a partner, or to use the more generic term, as an “older brother.” A stronger, and thus a more secure Russia, on the other hand, behaves towards Armenia as an overlord, one that dictates terms and reinforces a rigid structure of dependency. In this context, an insecure Russia values Armenia, while a secure Russia views Armenia as expandable. An insecure Russia remains more considerate of Armenia’s interests, seeks relations that are mutually advantageous, and qualifies Armenia as an important ally. A secure Russia remains indifferent to Armenia’s interests, qualifies Armenia’s interests only through the domain of Russian gains, and qualifies Armenia as a satellite or a subservient actor, not an actual ally. The results of systematized content analysis of Russia’s positions towards Armenia, in relation to Azerbaijan, from 1993 to 2022, confirms these findings. There is a robust negative correlation between the strengthening of Russia, the formation of a more secure Russia as regional hegemon, and decline in Russia’s support towards Armenia vis-a-vis Azerbaijan.

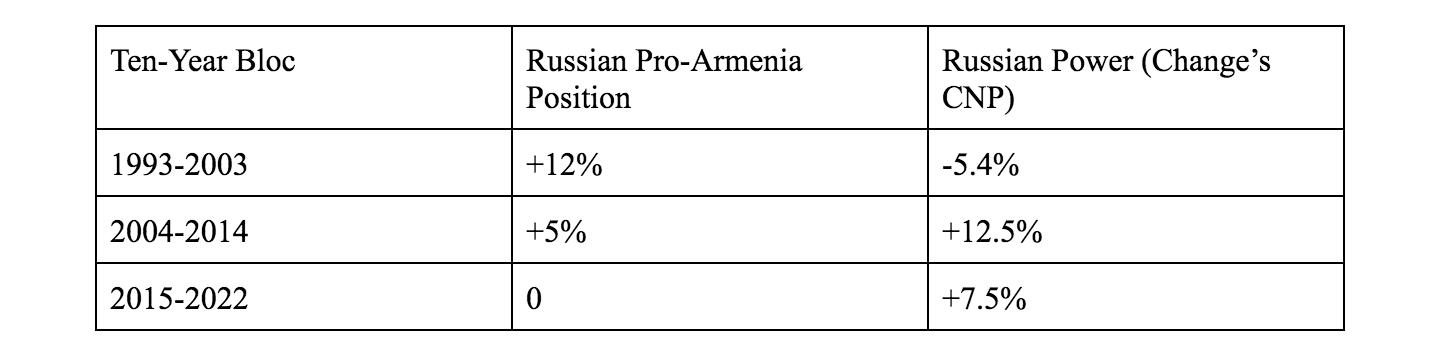

Russia’s positions towards the Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict have exponentially changed during the three ten-year blocs I constructed for the content analysis. The three blocs are: 1993-2003, 2004-2014, and 2015 to present. Declarations, communiques, public statements, and official positions of the Russian state have been aggregated for each ten year bloc, and then quantified to gauge the percentage of these positions as pro-Armenian or not pro-Armenian (either neutral or pro-Azerbaijan). Russia’s national power, as measured both by the Composite Index of National Capability (CINC), as well as Chang’s Comprehensive National Power Formula (both use Correlates of War dataset), is correlated with the changes in percentile of Russia’s pro-Armenia positions.

The table below displays the output. The “Russian Pro-Armenia Position” is the difference in the aggregate quantification of the content analysis data collected for each ten-year bloc, and the “Russian Power” variable is the percentile increase in the aggregate ten-year bloc of Russian power as measured by Chang’s CNP Formula.

The findings are quite straightforward: the stronger that Russia has become, the less “pro-Armenian” its positions have also become. These findings are also supported by the process-tracing of trends and patterns in Russian behavior.

From 1993 to 2003, Russia’s position toward Azerbaijan, and Azerbaijan’s close relationship with Turkey, were qualified by the Kremlin as negative and contradictory to Russian interests. An insecure and weaker Russia had very little tolerance towards Turkey’s presence within Russia’s sphere of influence, especially as these inroads were made under the presidency of Azerbaijan’s Abulfaz Elcibey. Even after Heydar Aliyev assumed power, the Yeltsin Administration continued to view Baku with suspicion, and Russia’s policy within the region remained consistently pro-Armenian. Content analysis for this ten-year bloc demonstrates that Russia’s official positions were +12% pro-Armenian.

By 2004, the Putin Administration overhauled Russia’s military, mitigated internal domestic and economic instability, and began the drive to re-strengthen Russia, as observed by the increase in its CNP metric. As Russia’s power increased, its pro-Armenian posture declined by 7% during the bloc period of 2004 to 2014. As Russia began posturing itself as a rising global power, it recalibrated its regional policies, thus enhancing relations with Azerbaijan, while slowly starting to consider Armenia as a satellite, and not an equal partner. As Azerbaijan and Russia enhanced their economic cooperation in the Caspian Region, and as Azerbaijan became a large market for Russian arms, Russia’s policies towards the region became more balanced than pro-Armenian.

After 2014, Russian power had exponentially increased, qualifying Russia as the unmatched regional hegemon, and this correlates with Russia’s completely balanced posture with respect to Armenia and Azerbaijan, as the “difference in position” became “0”. For the bloc of 2015-2022, Russian policy has been meticulously balanced, and has shed any of the pro-Armenian positions that were prevalent in the previous two decades. Even during periods of intense conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan, whether the 2016 Four Day War, or the 2020 Artsakh War, Russia relied on “bothsidesism” and displayed a pro-neutrality posture. This has been further confirmed by Russia’s position on Azerbaijan’s incursion into Armenia-proper after the 2020 War: Russia remains neutral, as opposed to supporting or siding with its ally Armenia.

Conclusion

The dyadic model, in this context, provides an important projective analysis into gauging Russian behavior with respect to Armenia-Azerbaijan relations, and demonstrates that a stronger and more secure Russia is not pro-Armenia, while a weaker and insecure Russia values Armenia exponentially more. Considering the developments with the war in Ukraine, the overall decline that is being observed with Russia’s capabilities, and the inevitable and exponential decline in Russia’s CBP metric, Armenia must utilize its current strategic shirking policy while formulating a long-term doctrine of re-engaging Russia. As the empirical findings show, a weaker and less secure Russia is conducive to assuming a more pro-Armenia posture, and Armenia’s strategic approach should revolve around exploiting this dynamic. A friendlier and more vulnerable Kremlin will also give Armenia much space to enhance its relationships with other friendly nations, thus reinforcing a multi-tiered foreign policy defined by strategic engagement. To this end, the insuperable situation that Armenia finds itself in because of the Russo-Ukraine conflict can be mitigated through a policy of strategic shirking, while the pending decline of Russian power can allow Armenia to turn a difficult situation into a highly beneficial one. What may seem as a pending disaster need not be, and Armenia can come out of this crisis in a much stronger and strategically sound position: it must avoid the elephant in the room, and once the elephant is removed, capitalize on the outcome.

New on EVN Report

Vision: A Seat at the Table

Can the inclusion of women help prevent conflict and sustain security post-war? A large body of research attests that it can.

Read moreAre There Alternatives to Delimitation and Demarcation of the Borders?

Reckless steps or imposed decisions regarding demarcation and delimitation, which are part and parcel of the so-called peace treaty between Armenia and Azerbaijan, might bring unintended historical consequences for the future of Armenia.

Read moreInternational Community Must Prevent Azerbaijan’s Creeping Ethnic Cleansing in Nagorno-Karabakh

Latest developments in Nagorno-Karabakh demonstrate Azerbaijan’s intent to ethnically cleanse the indigenous Armenian population and highlight the necessity of introducing international norms in the peacekeeping architecture there.

Read moreAzerbaijan’s Ongoing Policy of Ethnic Cleansing in Nagorno-Karabakh

Azerbaijan’s main goal is the removal of ethnic Armenians from Artsakh through the creation of conditions unfavorable for living, as well as creating an atmosphere of fear among the Armenian population.

Read moreAzerbaijan’s Gas Blockage of Artsakh Escalates to Attack on Parukh Village

After weeks of blocking gas supply to the population of Artsakh, the Azerbaijani Armed Forces launched an attack in the Askeran region, taking control of Parukh village and surrounding positions. While the international community has offered concern, sanctions are what’s needed.

Read moreAzerbaijan’s Five Points for Normalization of Relations and Armenia’s Response

Baku is consistently thwarting all post-war negotiations and existing formats, as the sole agenda of Aliyev’s regime is the total annihilation of Armenians from Artsakh, and possibly even the Republic of Armenia.

Read moreWaking Up to History: Putin’s War and the Historical Precedent of WWI

Media commentators, analysts and historians have all scrambled to draw historical parallels to make sense of Putin’s recent aggression toward Ukraine, but there have been relatively few nuanced references to World War I.

Read moreIl Risorgimento Italiano and the Armenian National Movement

In trying to understand what nationalism is or if it can be strictly national, this article re-examines the Armenian national movement of the 19th century in relation to the Italian Risorgimento.

Read more

Interesting analysis, but what about the moral standing of Armenia? Does it shrink into an invisible state without a moral compass as it watches another genocide unfold?

Very interesting indeed and I hope our current government can practice the “strategic shirking” to the best of its capability. As for the comment, equating the events unfolding in Ukraine to genocide, as it seems to be the case with all politicians including Biden, degrades the value of the word as it applies to the Armenian genocide. It took the US only over 110 years to acknowledge the atrocities which wiped out half of our population as genocide but they can not stop the repeated calling of the events in Ukraine as genocide. The imposed war in Ukraine, as unjust as it might be, has both sides armed evenly and yes, there are a lot of innocent people dying. I don’t recall any politician in the west referring to the hundreds of thousands of lives perished in Afghanistan or Iraq as Genocide.