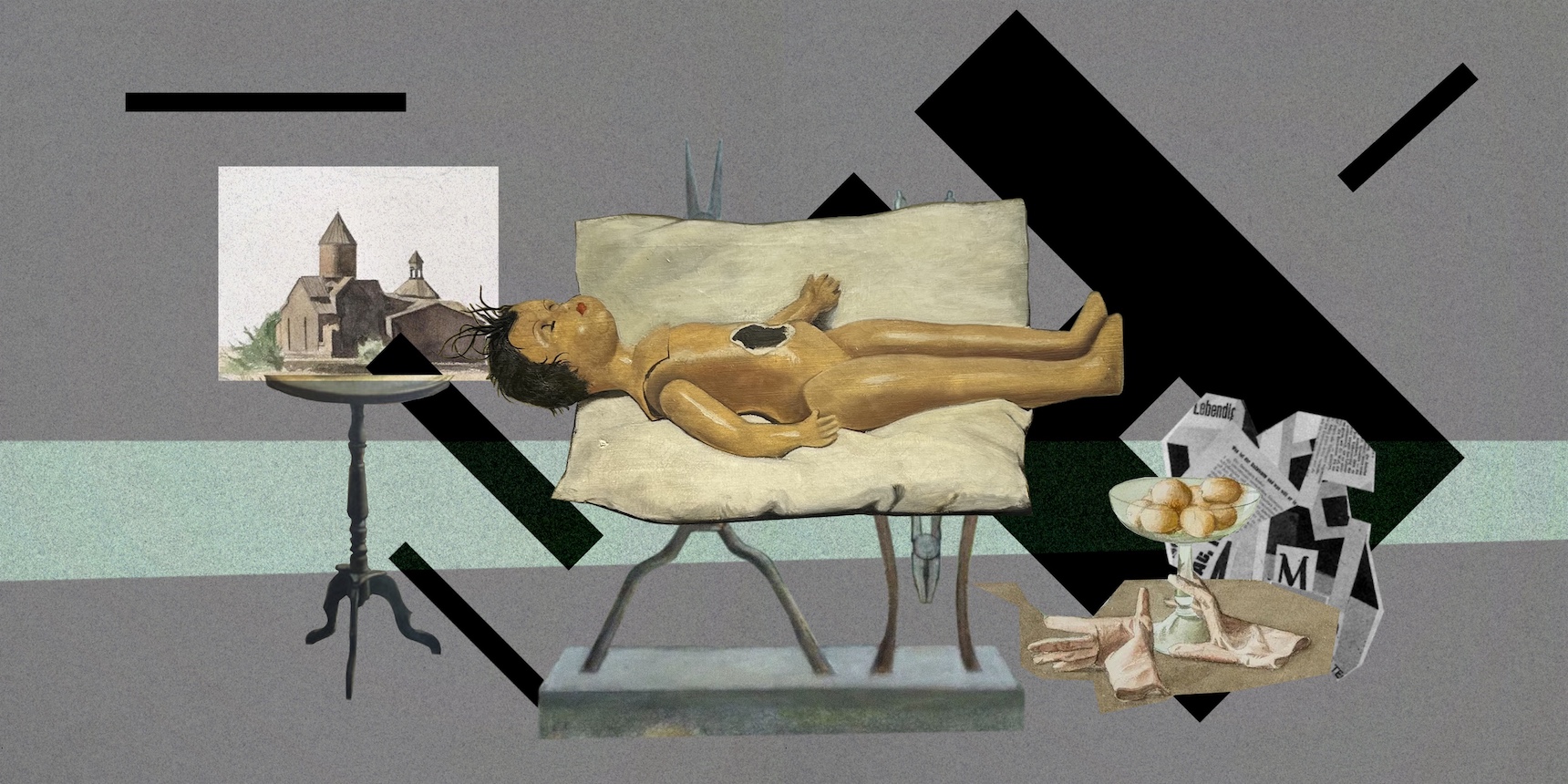

A vinyl doll, shorn off its clothes lies on its back across a white pillow set on a stool. With disheveled hair and shut eyes, the toy appears like a stiffened carcass – at once an image of tranquility and distress. Disturbingly, a large gaping hole has been punched in its stomach, creating an ominous void in the middle of this painting by the Egyptian-Soviet-Armenian artist Hagop Hagopian (1923-2013). Dated 1960, it is being shown for the first time in a large-scale retrospective exhibition dedicated to the artist’s centenary, which opened on October 10, at the National Gallery of Armenia. In its shocking harshness, ‘The Doll’ is just one of the many fascinating revelations in this sprawling presentation curated by Margarita Khachatryan. The exhibition forces us to rethink the true significance of this artist’s seven-decade long career in the annals of Armenian art, whose course radically shifted during the 1960s thanks to Hagopian’s incisively modernist and unsettling vision.

“The Doll” is striking not just as an unnervingly simple display of violence and rupture. It also hits a jarringly unusual historical note. In 1960, Armenian art was busily recalibrating itself as a manifestation of national culture. Emboldened by Nikita Khrushchev’s reforms in Soviet Armenia, the first wave of post-war modernist masters such as Hovhannes Zardaryan, Minas Avetisyan and Hovhannes Minasyan were reanimating the forgotten streak of the 1920s-1930s Armenian avant-garde in a new manner. Rebutting the ideological basis of official Soviet art, they turned towards the exploration of subjective visions and the search for “timeless” values which they saw as the underlying essence of Armenian identity.

Meanwhile, across the amorphous terrain of the Armenian diaspora, first and second generations of the 1915 Genocide survivors made loosely correlated attempts to deal with the trauma of that catastrophe by forging some sense of continuity and healing. Focusing on subjects that were deemed to be under “threat” from rampant industrialization, urbanization and globalization, prominent figures like Jean Carzou, Jean Jansem, Armiss and Samson Samsonian made allegorical and spiritually-heightened tributes to the life-affirming bonds of family, motherhood, community and cultural traditions. While distinct in their individual manners, these artists shared a nostalgia for an idealized past, a search for a new humanism and a disdain for the “soulless” rationalism of modernity. All of which imbued their work with emotiveness that at times bordered on unabashed sentimentality and pathos.

Remarkably, none of this emotiveness is present in Hagopian’s work. Despite its potentially melodramatic subject matter (a mauled child’s toy), “The Doll” is entirely devoid of mawkishness. In its bleak starkness and almost pornographic directness, the image has more commonalities with the anarchist sensibilities of the dadaists than it does with the restorative positivism of his compatriots. In fact, it is difficult to recall another work from Armenian art of the period that is so unapologetically negativist in its expression. As a visual metaphor, “The Doll” is emphatically about the death of an old, more innocent world, whose body appears to us like a “beautiful (but also artificial) corpse” so enamored by the surrealists, who were eager to show us the inherent rot in our reality. It is, in many ways, the embodiment of a flawless modernist painting – questioning, doubtful and steeped in ambivalence. So where did this unblinking aloofness come from, and how does it fit with the more common assumptions about modern Armenian art?

Hagopian was born in Alexandria, to a family of survivors from Ayntap. His parents made sure that their son received a proper education and sent him to study at the respected Melkonian College in Cyprus despite their meager means. The penchant for the visual arts manifested itself early in Hagopian’s life and after returning to Egypt, he moved to Cairo, entering the local Arts Academy in 1944 where he was taught by one of the great masters of modern Egyptian painting, Onnig Avedisian. Avedisian’s ability to thoughtfully adapt the stylistic innovations of European modernism to his own sensibilities must have served as a strong compass for his student, who would go to Paris to further his education at the Académie Chaumière in 1952, but remained unmoved by the more cutting-edge trends. In fact, following World War II, much of the Parisian art scene had abandoned the radical avant-garde ambitions of the earlier decades. Turning instead towards introspective contemplation of the simple joys of life, artists like Bernard Buffet reflected on the broken ideals of human civilization in which modernist art had its share of guilt.

That was the direction pursued by many of Hagopian’s Parisian compatriots, two of whom, Carzou and Jansem were already making a name for themselves as poets of doom and “miserabilia”.

Taking stock of these tendencies and clearly inspired by Buffet’s severe linear style, Hagopian returned to Egypt in 1954 feeling artistically paralyzed by this mood of despondency in which the visual arts no longer seemed to have a proactive social imperative. On the other hand, the Egypt that he was returning to was a hotbed of transformations following the 1952 revolution and the establishment of the Egyptian republic. Here was a place where the festering colonial order was violently decanting into the past under the furious forces of repressed national consciousness. The Middle East as a whole was quickly turning into a crucible of fresh and untested paradigms that instilled local contemporary art with a renewed sense of political urgency.

As evidenced by a handful of 1950s works included in the exhibition, Hagopian’s response to these momentous events was typically reserved and subtle. He had arrived from Paris as a fully-formed artist with a style that managed the feat of being distinctly contemporary and rooted in the realist tradition at the same time. The subjects he chose to portray seemed removed from the tumultuous political situation of the time. We see ordinary people — a waiter, a tailor, a housewife — and their banal surroundings. But there is an imperceptible strangeness to all this mundanity: the people and their environment are separated and shown apart. The figures are placed in an indistinct void, as if they have been suddenly unmoored from their social contexts and left without any direction. This mood of uncertainty also permeates Hagopian’s still-lives. Though not explicitly “post-apocalyptic”, these everyday household compositions are also filled with the dread of abandonment and absence. People have seemed to have left these objects just seconds ago, but the eerie stillness of these still-lives suggests that they may never return to reclaim them.

Looking at these still-lives from 70 years ago, it is hard not to think about the thousands of similar scenes around the cities and villages of the ethnically-cleansed Artsakh: kitchens and corridors with utensils resting silently in their places after their owners rushed through the doors, scurrying for their lives. This resonance makes me wonder if Hagopian is, actually, the artist that managed to most lucidly articulate the tragedy of the modern Armenian experience and give it universal relevance. His frugal still lives, austere landscapes and lone figures, which would culminate in the chillingly surreal paintings of the 1980s-1990s, hint at a catastrophic break in humanity’s ecosystem. From painting to painting, a vision of a post-human world gradually unfolds, revealing the fragility of the fundaments that we’ve taken for granted – our connection to nature, to place, to memory, to community and to ethics.

In 1962, Hagopian made the decision to move to Soviet Armenia as a way of attaining some sense of recuperation and direction. Speaking about his joy regarding this event in a 1985 interview with the Lithuanian poet Juozas Nekrošius, the artist claimed that for the first time, “the fatherland… became a tangible reality for me… [and] I wanted to study it, meld with it. That is why I primarily painted landscapes initially.” For a second generation diasporan, the feeling of a “tangible fatherland” would indeed come as an emotional boon, especially when one was arriving in the culturally progressive atmosphere of 1960s Yerevan. However, what Hagopian left unsaid was the fact that this move was also predicated by the drastically worsening conditions for the Armenians in Egypt.

The growing nationalism and Islamic fundamentalism that followed the 1952 revolution made life increasingly difficult for the Egyptian-Armenian communities, who had flourished in the cosmopolitan atmosphere of Cairo and Alexandria during the French and later British colonial rule. Hence, these affluent Christians — along with the Jews, Greeks and the French — were seen as an undesirable remnant of foreign power, leading to severe limitation of civil liberties and eventually a mass exodus under president Nasser’s oppressive regime. By the mid-1960s, most of the Armenian population of the country had dispersed across the world, effectively putting an end to one of the most vibrant, active and culturally significant diasporan centers, as well as Hagopian’s burgeoning reputation as a rising star of the contemporary art scene.

This rupture solidified the artist’s position regarding life as an endless succession of vicissitudes. The promise of Soviet Armenia as the long-desired abode of all the Armenians was certainly a consolation, but the encounter with the historical fatherland “reborn” under the aegis of communism, only deepened Hagopian’s critical suspicions and the sense of alienation that underlies so much of his work. It is not that he was made to feel as an outsider. He was enthusiastically welcomed by Yerevan’s art establishment, which was already familiar with his work, and feted him as an important master whose art, in the words of noted art critic Alexander Kamensky, “became an event – first in Armenia, then quite far beyond.” And yet, Hagopian was not in a rush to give in to “homeland adulation”, but went on to methodically scrutinize this strange environment, in order to reveal its inherent slippages and paradoxes.

This was precisely the “event” that Kamensky had hinted at in his 1975 essay on the artist. Hagopian’s arrival in Armenia was akin to a brusque intervention in the local art scene, which by the early 1960s was set into a distinct mold, brandished by the Soviet establishment as a successful example of a “national” school of socialist art. Frequently described as “colorful”, “decorative”, “life-enforcing”, “positivist” and “folkloric” in Soviet art criticism, Armenian modernist art was largely content to accede to such generalizing and frequently patronizing perceptions, notwithstanding the occasional forays into darker areas of metaphysics and psychological disquiet. What Hagopian was bringing with him instead, was a politics of dialectical reasoning that questioned staid notions of the homeland, modernity (socialist, or otherwise) and the rationalist investment in technological progress.

He “unleashed” these approaches gradually, in a customarily surreptitious manner, by turning to what was in his immediate vicinity – in this instance, the provincial landscapes around Gyumri, where the artist’s family was initially relocated to. A key motif in Soviet Armenian art, this genre was entirely novel for Hagopian’s oeuvre. These elegant, stripped-down and almost monochrome paintings of village and town views were as extraordinary in their effect, as they were mundane in their subject. Nobody had seen or portrayed Armenia in quite the same way up until that point, with the notable exception of Vardges Surenyants, whose seminal 1891 painting Hripsime Monastery may well have inspired Hagopian and served as his melancholic “anchor” within the history of Armenian art.

The prosaicism of Hagopian’s landscapes — bland street vistas in Leninakan, or a jumble of hovel-like houses and manure pyramids in Aghavnadzor village — was dramatically underlined by the painter’s ascetic style. Seen during deep autumn and late winter months, these sights appear as scorched and alien territory shrouded in chilling silence. People are nowhere to be seen, though their presence is clearly felt in the traces of contemporary life – paved sidewalks, electricity polls, or a ladder propped-up on a wall. But the absence of humans turns these locations into something akin to a crime scene that is “cleared out” by the artist for forensic investigation.

What exactly was he examining here? Was it simply an outsider’s way of trying to gauge an unfamiliar environment that was meant to be both a sacred homeland and a new home? The Armenia seen in Hagopian’s canvases comes as a retort to the operatic promised land fashioned by Martiros Saryan during the 1920s and subsequently turned into the country’s meta-image. In contrast, the arid, almost Martian landscapes painted by the repatriate artist provide little comfort or, moreover, certainty. They reflect the artist’s sense of unease towards this strange place where modernity and tradition, nature and man are entangled in an ambivalent, even torturous struggle.

By exhuming this ambivalence, Hagopian was changing the lens on the idea of Armenia as a mythical topos, an atavistic construct of the Armenian paradise. What he foregrounds and makes evident instead, is a land of extreme harshness and desolation in which life can happen only as a product of tremendous effort and unconditional belief. And the fact that this Armenia even exists suddenly becomes something akin to a miracle, a fantastic spectacle of the human spirit wrestling with its own insignificance against the untamable forces of time and history.

But it would be a misnomer to think that the artist had given in to patriotic gesticulation. He does not emphasize any of the expected picturesque signposts that toggle the strings of nostalgia, collective pride or the outsider’s thirst for the exotic. The artist even avoided painting Mount Ararat for years, claiming that he didn’t know how to see this all-encompassing symbol of “Armenianness”. The Armenia he presents in his landscapes is a frustrating paradox where depressing blandness is sharply interposed with the overpowering sublimeness of nature. What grows in this inhospitable realm, manages to do so with great exertion: the dry shrubs of grapevines twist as if in agony and exposed tree roots peek out from the parched earth like skeletal limbs. The impression one gets from Hagopian’s landscapes is of a vista saturated with pain, where life is born against the odds and through enormous suffering.

What has drawn people to these corners for thousands of years, made them so bound to a land so unyielding? Is it mere stubbornness against the winds of fate, an obstinate refusal to accept the outcome of centuries of dispossession and genocide? Perhaps it is some mystical force that pulls these specific people into a spellbound bevy, like the men Hagopian depicts in one of his strangest paintings, seen from the back, packed together in an absolutely blank environment, staring in transfixion at some unknown phenomenon. But like a true modernist, he abstains from giving us ready or soothing answers. What he does present with brilliant clarity, however, is the notion of Armenia as an Idea that constantly struggles to materialize into a place. When he paints Ararat, it appears divorced from the earth, like a mirage floating in the clouds; iconic monasteries are shown as miniscule fragments of a long-disappeared past perched on the precipices of gorges; the dried-up waters of Lake Sevan have pull back to expose primordial gray stones reminiscent of rotting corpses while modernity repeatedly comes in the guise of wooden electricity poles that are ominously reminiscent of crucifixion crosses…

A 1972 painting (unfortunately absent from this retrospective) called “Terminal” crystalizes these observations into a lucidly surreal image: a group of mannequins, dressed in lavish evening clothes stand by a perfectly smooth asphalt road that slashes through a dry hilly landscape dotted with a row of evenly-planted but bare fruit trees. Modernity’s presence in this primeval environment — articulated through disembodied, or empty signifiers — comes as a rude, even destructive intrusion, resulting in a spectacle of absurd incongruity. And how could it be otherwise? At the height of Brezhnev’s regime in the 1970s, Soviet Armenia was a miniscule province existing under the colonial boot of a gigantic empire, given all the administrative and institutional trappings of a state without actually being one, a realm whose inhabitants were prohibited from dealing with their tragic past and forced to repress their traumas for the sake of some fictitious Utopia. As a child of Genocide survivors, Hagopian understood perfectly that this unaddressed pain was transforming into an abscess of discontent, which would grow and spread like a rot inside this socialist prison of order and “harmony”.

No surprise then that when Hagopian started to paint his first portraits of actual individuals, or continued to develop his series of metaphorical figures, such as the unnerving “Woman with a Mirror” (1969), he showed them in isolation, often encased in cell-like spaces where these contemporary personages appear to be overcome by profound melancholy, nursing some undefinable inner disquiet. They do not exhibit a tangible connection to the outside world, which has been replaced by a despondent awareness of the fallacious and oppressive reality and their powerlessness to do anything about it.

Hagopian, despite his insistent self-effacement, was one of the few intellectuals in Armenia brave enough to draw back the curtain on these issues. Resisting the temptation to serve the self-mythologizing machine of the communist state, or (unlike many of his contemporaries) to withdraw into a socially-disengaged world of the subjective imagination, he gently and elegantly continued to deconstruct the faults inherent in the officially propagated definitions of Armenia and modern, industrialized society in general. All of which, arguably, makes him the most uncompromisingly political Armenian artist of his time – an aspect of his legacy that has remained remarkably, and criminally ignored.

But, in the end, what makes Hagopian’s work so substantial for Armenian cultural modernity is the evasion of nihilistic apathy and cynicism that pervaded so much of global contemporary art after the 1960s. His representations of Armenia as place, as nation and as culture may be streaked with arteries of doubt, suspicion and irony, but they powerfully underline its existence as an undeniable fact – in spite of its contradictions. In fact, it is these same paradoxical, seemingly irreconcilable circumstances through which life and belonging somehow continue to endure in this place that the artist finds so fascinating and significant. Rather than being a mere critical deconstruction of the modern Armenian experience, the artist wants us to understand and appreciate the latter’s very existence as an extraordinary phenomenon that must be treasured and nurtured at all cost.

By pointing out the incessant rifts in our historical narratives, Hagopian’s art consistently reminds us of the tenuousness of any kind of cultural or national reality in today’s ever-chaotic and ever-violent world, which he bluntly addresses in his late post-apocalyptic paintings tackling the threat of nuclear war. While celebrating Armenia’s miraculous persistence into the modern era, the artist also makes visible the unresolved issues at the heart of it, urging us to understand its precariousness and fragility, and to not take anything for granted. It is just one of the many insightful lessons in Hagopian’s rich oeuvre, and the fact that these messages have, tragically, become prophetic today is a testament not only to the lasting power of Hagopian’s art, but also the urgent need to reassess the history of modern Armenian art as a blithe idealization of the country and the nation.

Et Cetera

Headfirst Into the Rabbit Hole: An Ode to Cultural Anxiety

Self-pity and victimhood have served as comfortable escape routes from pervasive issues, however, in the current post-war reality there are clear signs that there is a desire to address the fault lines, to understand and rethink the reasons behind past failures, to stop and reflect.

Read moreExhibiting “Armenian” Nudity: A Decolonial Approach to Art History

A recent exhibition “The Guises of the Nude: Perceptions of Nudity in Armenian Graphic Arts” provided a powerful opportunity to challenge prevailing meta-narratives and foster a self-reflective dialogue that can contribute to the broader project of decolonization and social transformation.

Read moreThe Regional Policies of the Cannes Film Festival

Major film festivals don’t only showcase films for local and international cinephiles, they also create opportunities for unknown stories, names and voices to be heard. Sona Karapoghosyan writes about how the Cannes Film Festival is trying to tell the stories of everyone, not only ones from the West.

Read moreLiving Portals: Reflections on Territorialization in Contemporary Armenian Art

A review of an exhibition in the village of Verishen in Armenia’s Syunik region featuring a contemporary carpet collection by Goris-born artist Davit Kochunts, examines the concept of social space and the process of territorialization.

Read moreDon Quixote: Present and Absent in Armenian

The Armenian translation of Cervantes’“Don Quixote” has not yet reached readers, despite being a masterpiece of world literature. Aram Pachyan delves into the reason behind this.

Read moreA Vision of Power: The Royal Crowns of Cilicia

Crowns worn by monarchs reveal stories of hierarchy and power, providing insight not only to those who wore them, but the strata to which they belonged. Margarita Ghazaryan looks at the story of the royal crowns of the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia.

Read more5 Dreamers and a Horse

The directors of the documentary “5 Dreamers and a Horse” manage to think outside of genre limitations, and to blend the elements of magical realism and cinéma vérité to create a strange fairy tale that resembles the one in which we all live.

Read moreLove and [un]Love in “The Miracle Worker”

Nune Hakhverdyan reviews the Armenian production of “The Miracle Worker” staged by the Gyumri Drama Theater and Yerevan’s Hamazkayin Theater about the life of Helen Keller, and examines the relationship between parent and child.

Read moreExhibition Outside of the Traditional Art Space

In Armenia, there are few exhibitions outside of the traditional art space environment, but at the same time, one can notice distinctive new trends emerging in recent years.

Read moreThe Armenian Dream: Michael Goorjian’s Film About Charlie the Repatriate

Michael Goorjian’s feature film “Amerikatsi” succeeded in infusing a sentimental and “positivist” tone inherent to Hollywood cinema within an Armenian reality, writes film critic Sona Karapoghosyan.

Read more