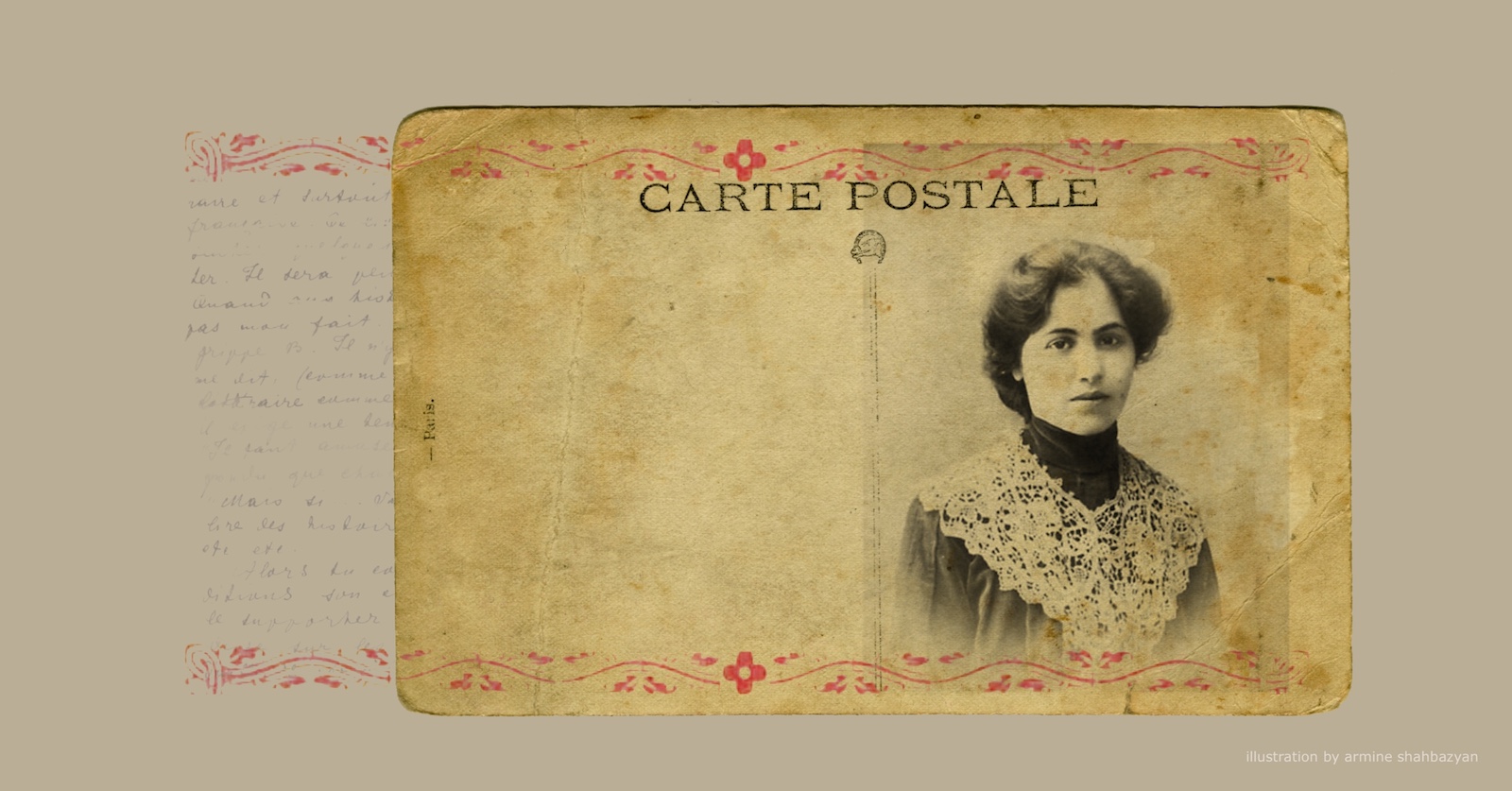

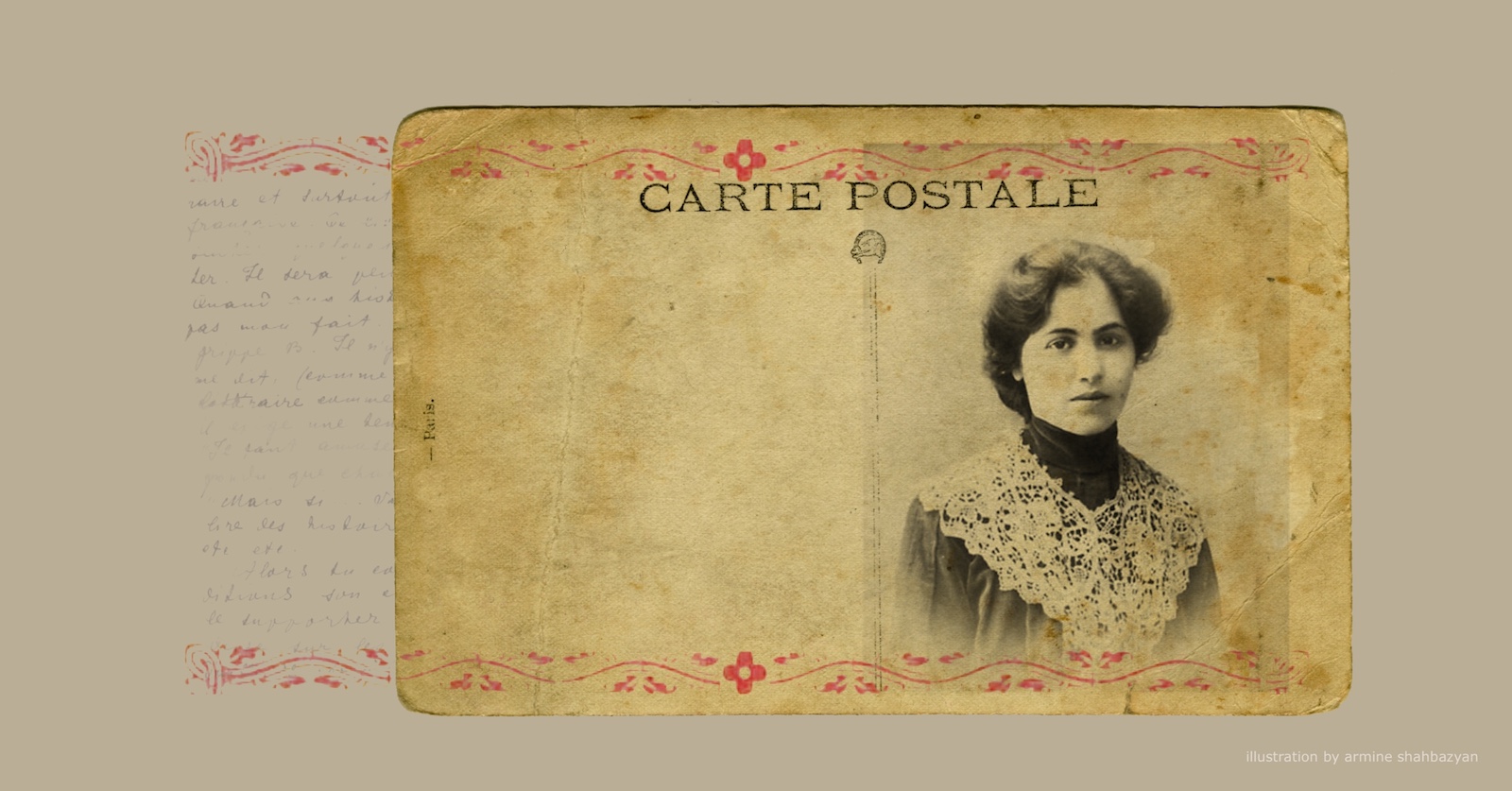

The personal letters of prominent Armenian writer, literary critic and public figure Zabel Yesayan (1878-1943), were collected over many years and later compiled into a book by literary scholar Arpik Avetisyan — my maternal grandmother. The collection of letters (Zabel Yesayan, Letters, Yerevan, 1977) was never really complete as not all of Yesayan’s correspondence held at the Yeghishe Charents Museum of Literature, where my grandmother worked, were included in the volume.

When poring over my grandmother’s personal archive, it also became evident to me that some of the letters in the museum’s possession had never been published.* Recently, I discovered an unpublished copy of a letter Zabel Yesayan had written to artist Hovsep Pushman in Arpik’s archive.

Pushman was an Armenian-American painter, born in 1877 in Diyarbekir in the Ottoman Empire. His family had fled to the U.S. in 1896 to escape the Turkish massacres. Pushman later moved to Paris and studied at the Academie Julian before returning to the U.S..

In 1926, while living in Paris, Pushman headed “Ani”, the Union of French-Armenian Artists, which included about 20 artists such as Edgar Shahin, Hakob Gyurjian, Hovhannes Alkhazian, Rafael Shishmanyan and others. Martiros Saryan also participated in exhibitions organized by Ani.

Yesayan’s letter to Pushman was also not included in the special edition, which was published later in 1985, and contained Yesayan’s other unpublished letters.

The original letter resides in the archive of the Yeghishe Charents Museum of Literature and Art, but it is not in the archival funds of Zabel Yesayan or Hovsep Pushman. The copy of the letter in my grandmother’s archive is typewritten with the spelling partially changed to Eastern Armenian.

When writing the letter, Zabel Yesayan was excited about the prospect of the development of Soviet Armenia. At the invitation of Soviet Armenia’s government, she was to make a trip to the Soviet Union in 1926, specifically to Armenia, to learn about the “rebirth and progress” of the motherland. In the Diasporan press, Yesayan was accused of Soviet orientation with Pushman most likely defending her from such accusations.

The version of Yesayan’s letter to Pushman in our possession has been compared to the original. The version published below now corresponds entirely to the original and was written a year before Yesayan’s first trip to the Soviet Union.

December 15, 1925, Paris

Dear Mister Pushman,

I felt as if I could not fully convey my emotions to you personally. I wasn’t able to express myself because what I learned took me by surprise, and my impressions were befuddled . Today and last night, I contemplated for a long time. At times I felt sad, at times I got angry, and at times I was joyous. Weighing everything deeply in my soul and interlacing everything together, I saw that pure and unadulterated joy remained while the rest evaporated like smoke. This joy was the result of the kindred treatment you had the generosity to extend to me. This is no trivial matter. Of course, by showing me such treatment, you and your wife were guided by your unmediated inherent nature. I was by chance the reason, it could have been someone else. This reflects the enduring nature of your deep feelings. I was the indirect reason, setting one of the rays of your beautiful souls to shine brightly.

So, what is left for me to do is be thankful to those who intended harm but became the reason for a greater good. Of course, I didn’t need proof. Over the course of my life, I have had the opportunity to meet thousands of people and generally, I discern with preciseness, almost from the first meeting, the inner qualities of people. But acquiring new evidence for something I was convinced of brings me pleasure and joy, and this is why I wanted to express to you my feelings of happiness.

One day, a French acquaintance, who was a philosophy scholar, told me: “To understand and appreciate someone’s qualities or values, one must possess something similar.” Is it presumptuous of me to believe that there was something in me through which I was able to feel and appreciate the wonderful qualities of all your family members? In any case, it’s true that I feel that my appreciation of your treatment of me has somewhat made me a participant in its beauty and, consequently, elevates me and for which, again, I am thankful to you.

Just like evil, with its inspired rage and hate, can incite unworthy feelings in a person and even create a state where the menace caused is less significant than the feelings it evokes in the person succumbing to it, so too can good, and especially good, it does not limit itself to the act of goodness but creates more good because it radiates like light. However, one must not be blind and should accept those rays.

And here’s how I deducted the foul roles of the others in this incident, and submitted only your role to my memory. Therefore, I only feel joy when my mind strays to that incident.

Fueled by this enthusiasm, I worked the whole day, and I believe I worked well (inasmuch as I could). I’ve started writing a novel which, if I manage to complete with the same fervor as when I started, I believe will be one of my best works. I’m emboldened to have you be part of my hopes, considering you and your wife as my closest friends.

This and these types of matters are my primary concern, and upon which my and my children’s future depends, and not the futile intrigues and worthless and jealous writhing, which I prefer to leave to others.

I ask that you accept my warm sentiments and give my kind regards to your lovely wife and sons.

Always yours devoted,

Zabel Yesayan

P.S. I find it prudent to inform you that Vardanian has discussed this issue with Choubar, who mentioned it to me on the side. Some circles are very upset and have decided to take action. It’s clear to me that they’ll defend me by all means if necessary. I write these details for you to know that if this matter is mentioned, it’s not because I have broken confidentiality. The matter can become a problematic issue. I’ve acted as if I was unaware, as was necessary.

Please excuse the irregular style of my letter. There were many things I wanted to say, but was only able to express a few of them. But as much as the style is incomplete, its depth is a direct and intimate expression of my feelings.

In 1926, Zabel Yesayan visited Soviet Russia and Armenia. She stayed in Armenia for eight months.

“I have been in Moscow for two days, and I can honestly tell you that I am in a constant intoxication of wonder… I feel free, relaxed, and safe… The opinion that people live in fear and terror and their tongues are tied is a lie and slander,” she wrote in a letter addressed to actress and director Anna Budaghyan from Moscow on October 17, 1926. [1]

By 1933, Zabel Yesayan had moved to Armenia at the invitation of the Soviet authorities and was teaching at Yerevan State University. It was here that Yesayan would write her powerful memoir, “The Gardens of Silihdar” that was published in 1935.

To this day, there is no comprehensive study of the literary atmosphere of that time period in Soviet Armenia, more specifically, of the 1930s. Writers who fell victim to Stalin’s repressions are viewed as victims, while those who survived are perceived as executioners who sent them to their deaths. Archival documents, press from those years, personal letters, and writers’ memoirs paint a grim picture. Almost all writers of that period, with a few exceptions, wrote defamatory letters against each other and contributed to isolating one another from the literary scene and society at large. There was one justification: these were terrible times, and if you don’t accuse someone, you will be accused yourself.

Zabel Yesayan also had to become part of this cycle. Grakan Tert in its 1933 issue (N9) reflected on her commentary about her contemporaries:

“Comrade Yesayan mentions several new, young writers, such as Shahan Shahnur, Vazgen Shushanyan, Nshan Peshiktashlyan, and others. Some who criticize the past nationalist path but cannot find a way out, in fact, remain within Dashnaktsakan circles (Shahnur), or find nothing comforting and hopeful in contemporary life, and resort to the reproduction of biblical themes (Peshiktashlyan) or endorse wantonness and give impetus to pornographic literature (Shushanyan).”

In the same issue, a passage from one of Yesayan’s lectures is included where she talks about writer Kostan Zaryan:

“That half-educated intellectual, that writer who doesn’t command any human language, enjoys great esteem in the Dashnak press, but whoever has read his false, vile, slanderous memories of Soviet Armenia will see how pathetic the literature of that adventurous intellectual is.”

Zabel Yesayan’s door, however, was also to be knocked on one day, just as the doors of Charents, Bakunts, and many other writers had been.

On June 27, 1937, she was arrested and accused of being a foreign spy.

Interestingly, the last letter in Zabel Yesayan’s collection of letters was written in 1935. Neither the author of the book’s foreword, literary critic Sevak Arzumanyan, nor the editor of the volume, my grandmother, mentioned anything about Zabel Yesayan’s fate. Surely, the letters of such an active woman could not have abruptly ended in that year.

It’s important to remember, however, that the collection of Yesayan’s letters published in 1977, reflected that era’s stance: to remain silent and not even acknowledge that thousands of Armenian intellectuals had fallen victim to Stalin’s repressions.

Writer Clara Terzyan, a long-time journalist at Armenia’s Public Radio, knew Zabel Yesayan personally and conducted extensive research on the final years of her life. Even she was never able to uncover the circumstances of Yesayan’s death. How, where and when she died remain unknown.

Ashkhen Simonyan, who was also arrested in 1937, shared a cell with Yesayan at the prison of the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs. According to her testimony, Yesayan returned after every interrogation saying with a bitter smile: “They ask such absurd questions that I wonder how they make them up.”

One day, Yesayan was taken for questioning but returned only two days later. Her legs were terribly swollen. They had forced her to sit in a high place, leaving her legs dangling in the air. They tortured her like this, demanding that she sign a document admitting that she was a spy.

“On another day, they came once again and told her: ‘They’re summoning you with your belongings.’ This meant either exile or release. In such cases, detainees would agree that if they were released, they would send us something, like a comb. Then we would know that they had been released,” Ashkhen Simonyan recounted to Clara Terzyan. “Zabel Yesayan was taken away with her belongings. But since we did not receive the agreed-upon item, we assumed she was exiled.”

Months passed, and she encountered Zabel Yesayan, her hair unbound, in the city’s prison.

“Mrs. Zabel, where have you been? How did you end up here?” she asked.

“I came from the caravan of death, my girl,” Zabel replied. “From the caravan of death.”

Zabel Yesayan is sentenced to death by the tribunal. Nonetheless, she writes an appeal to Moscow, asking for exoneration.

One day, a guard found Yesayan lying on the ground, covered in blood. Blood was flowing from her nose, mouth, and ears. Her blood pressure had risen, and her loss of blood had averted a heart attack. They transferred her to a hospital. Meanwhile, the response to her appeal arrived from Moscow: her death sentence had been commuted to ten years of exile.

There are accounts of people who had seen her in the Baku prison. According to another account, Zabel Yesayan was scheduled to be transported by boat to Krasnovodsk. Suffering from diarrhea on the ship, she was thrown into the Caspian Sea.

Another theory about her death suggests that in Baku, she was put in a sack and brutally beaten.

The exact year of her death remains unknown. The “official” record states it as 1943. However, sources referenced by Clara Terzyan suggest it was 1939.[2]

*Over time, unpublished materials from this archive had been featured in different publications in Armenia including “Inknagir” magazine, “Hetq,” and “Mediamax.”

Correction: A footnote in an earlier version of this article said that, at the time of writing the letter to Pushman, Yesayan started working on her novel, “When They Will Never Love.” This was incorrect and has been removed.

Footnotes:

[1] “Zabel Yesayan’s Letters”, Yerevan, 1977, page 255.

[2] Azg, March 30, 2018

Also see

Zabel Yesayan: The Hope for Justice Hidden in a Matchbox

Hidden away in dusty archives, Seda Grigoryan discovered documents from a 1939 Soviet trial that found 20th century writer, literary critic and public figure Zabel Yesayan guilty of crimes she had not committed.

Read moreThis is the story of Arev, a woman who “who always wears Chanel suits in Almodovar colors that she gets from who knows where, red lipstick, and high-heeled shoes” who survived a Soviet prison. As told by her niece Ella Kanegarian.

Great article about Zabel Yesayan’s letter to Hovsep Pushman. There is however a mistake in what is written. The novel Yesayan mentions in her letter can’t be the book titled Երբ այլեւս չեն սիրեր: Քօղը: Վէպը:, as this same book was previously published in G. Bolis in 1914. I am not sure to which book she might be referring to, but most probably Պրոմեթէոս ազատագրուած. She has a book published in 1926 in Yerevan and titled Նահանջող ուժերը, but I am not sure if this was published in a periodical previously and made it in book form with revised orthography in Yerevan in 1926.