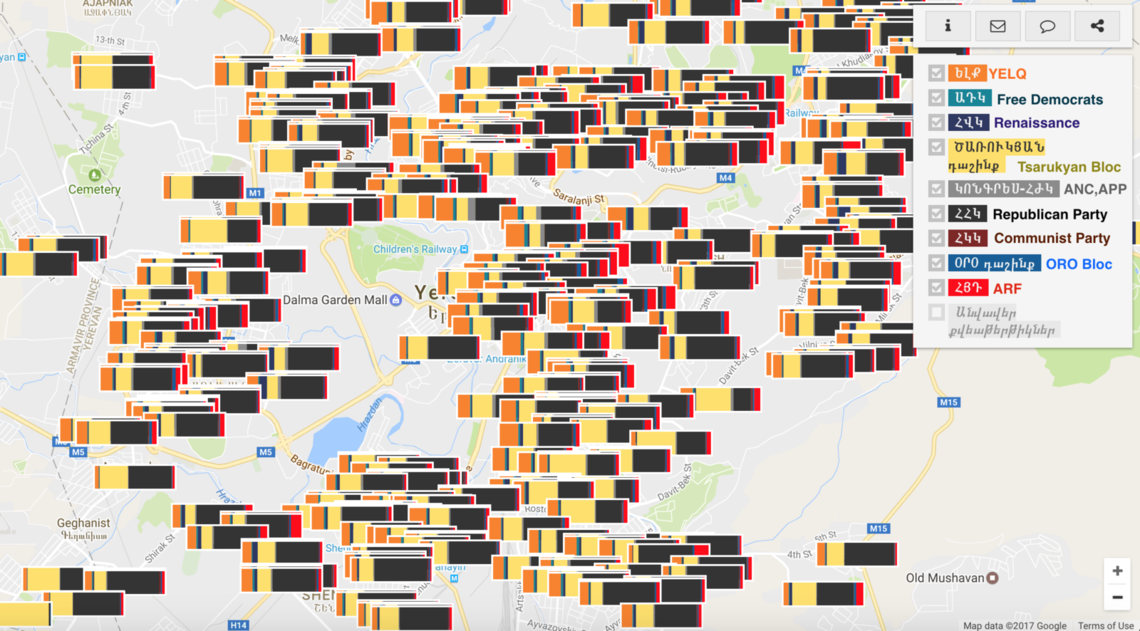

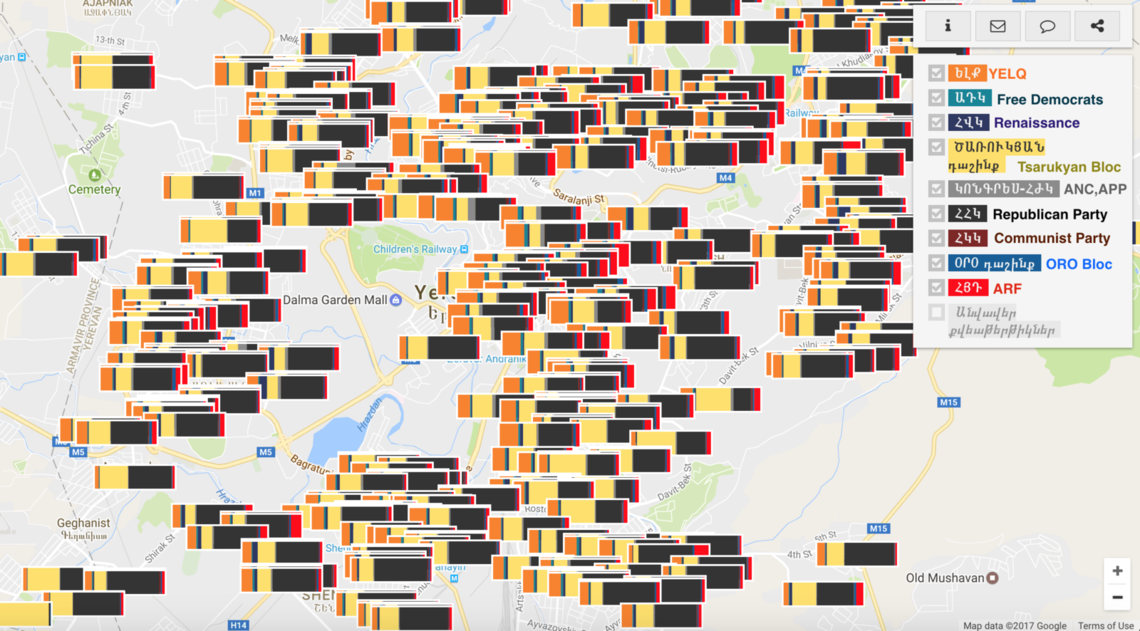

A color-coded map of the results of the 2017 Parliamentary vote in Armenia.

To nevigate the map, follow the link

If in the 1990 Supreme Council (parliament) the RPA was represented by one member, by the third convocation of parliament (2003), the Republican Party already had the biggest faction with 40 MPs. Currently, the party holds 54 seats in parliament.

The daunting reality that the Republican Party of Armenia (RPA) was able to secure a “stable majority” (54 seats out of 101) in parliament by winning 49 percent of cast votes on April 2 still haunts many in Armenia. What in hindsight seems to have been a very predictable victory, has left a bad aftertaste for three reasons. First, a party that has so poorly managed the country for fifteen years will now be in a position to lead again for at least another five years. Second, what appears to have been a clean vote was manipulated through abuse of administrative resources of the state. Third and most importantly is the widespread sense of apathy in society to cope with the current reality.

Smirks and cynical jokes made after the elections under the zeitgeist that things were bound to happen this way, underscore the trauma these elections have caused for so many. Indeed, after the revelation that 114 school and kindergarten headmasters were actively involved in enlisting people to vote for the RPA, the reaction from political parties and civil society was vocal but in practice very timid. Similarly, when an audiotape mysteriously surfaced a week after the elections, putting the SAS group under the spotlight for coercing its employees to vote for their patron Artak Sargsyan, the reaction from both the opposition and civil society was confined to social platforms.

To be sure, both cases have provided sufficient evidence to launch a criminal investigation. The first case is direct abuse of administrative resources, while the second case is an indirect one. Put simply, the state has the responsibility to ensure that its citizens are not exploited and enjoy freedom to pursue their political preferences. So, what can explain the general indifference in society even after such cases are exposed? The irony is that now the school directors are taking the Union of Informed Citizens (UIC), the organization that released the audio recordings, to court for defamation.

2017 Parliamentary Election Results

- Republican Party of Armenia – 49.17%

- Tsarukyan Bloc – 27.35%

- Yelq Bloc – 7.78%

- Armenian Revolutionary Federation- 6.58%

- Renaissance Party – 3.72%

- Ohanyan-Raffi-Oskanyan Bloc – 2.07%

- Armenian National Congress and Armenian People’s Party Bloc – 1.66%

- Free Democrats -0.94%

Communist Party of Armenia – 0.75%

A number of media outlets have extensively covered how the mechanisms of administrative resources work. Indeed, the general lawlessness allows the “lieutenants” of the RPA to intimidate and/or buy voters freely. It is also true that loyal state and RPA oligarchs provide employment for a considerable number of people, and they are likely to return the favour during elections. At the same time, this alone is neither sufficient to explain the election outcome nor the post-electoral detachment. Our soul-searching shouldn’t be limited to scratching the surface of political realities; we need to look beyond and into the heart of state and citizen relations.

In an article discussing the 2007 Armenian Parliamentary Elections, the Economist describes the Republican Party of Armenia as a “typical post-Soviet ‘party of power’ mainly comprising senior government officials, civil servants, and wealthy business people dependent on government connections.”

Nothing is True and Everything is Possible

Peter Pomerantsev’s excellent account of how the contemporary Russian state works “Nothing is True and Everything is Possible: The Surreal Heart of New Russia” can be extrapolated, with some caution, to explain the realities in Armenia too. Overall, we are not only strategic partners in security with Russia, but are also similar in the way we construct our social reality. Two leitmotifs run in Pomerantsev’s description of modern Russia. The first one is the mercurial nature of the ideology where everyone can freely identify as liberal, conservative, pro-Western, Russophile, as long as they are not following the trails of corruption. The second theme which is perhaps more characteristic for Armenian reality is “guilt by association.” Drawing on the example of army dodgers, Pomorentsev argues that the genius of the state is in allowing illegality to happen; while a young man escapes the draft, his family members are already hooked by the state sponsored illegality.

Similar to what Pomerantsev implies in his book, the political menu in Armenia has been adjusted to attract all sorts of political ideologies. If you are in favor of the status quo and you benefit from the shadow of daily malfeasance, you opt for the Republican Party of Armenia. If you are waiting for a messianic figure, there is an arm-wrestler tycoon, not in shining armor but in plain white suits here to be your king.

You are a nationalist and you love your country from far away? We have the noble Armenian Revolutionary Federation. You prefer none of the above and you want liberal, western-oriented younger generation kind of politicians? The regime is ready to offer that one too. You may embrace Yelq (“Way Out”) to wrap yourself in the fabric of an eternally perpetuating quasi-legal environment.

The second position of the book is even more valuable. The mundane system of favors, the manipulation of formal procedures for friends and relatives, parochial families are the breeding ground for “illusionary democracy.” It is a common feature of closed societies, that when everyone is “guilty” then no one is “guilty.” This being said, two caveats are to be made. It is not an attempt to exonerate vote-selling, rather it is a diagnosis of the dreadful situation. Secondly, I do not assume that each individual has been hooked in by a semi-illegal environment; however, it is clear that the majority has been. This theme is explored to explain the overarching taciturn attitude towards the illegality as well as the real mechanisms through which sizable pro-government minority agents are able to maximize their rank and file.

Pessimistic Conclusions

Armenia is facing both domestic as well as external challenges. On the background of the April micro-war and seizure of the police station in Erebuni by armed rebels last year, real reforms are more than pressing. The responsibility is squarely on the shoulders of the elected parties. Yelq (Way Out) is yet to institutionalize its diverse elements into a coherent party. The Tsarukyan Bloc should find some kind of strategy to brand itself as an alternative to RPA, although not much can be expected here. The ARF needs to reflect on how much is left from its social-democratic platform after acquiring the role of RPA’s junior partner.

Lastly, although the RPA was able to win the parliamentary elections, the conflicts within the the party itself seem eminent. President Serzh Sargsyan might appear as a lame duck but this is very far from the reality. He is keeping his options open: he may or may not pass the premiership to Karen Karapetyan in 2018 when his term as president is over. Some political analysts speculate that a middle-ground solution is possible, that Sargsyan will maintain formal representation in the power politics of Armenia and will designate Karapetyan as a successor. This is plausible scenario, but again “nothing is true and everything is possible” in Armenian politics.

Civil society as well as the opposition in Armenia should ensure three mechanisms in order to avoid what happened at the beginning of April. First, there should be a criminal investigation of the vote-buying cases under public oversight and there should be effort exerted to move away from the sad tradition of overcoming electoral cycles through violence or/and criminality. Second, ensuring job security regardless if the employer is the state or a private entity; this must be a priority for the political opposition. Lastly, in our everyday life we should reinforce formal procedures and strict legality as a habit that is not harmful to our social relations but bears the promise of a better future.