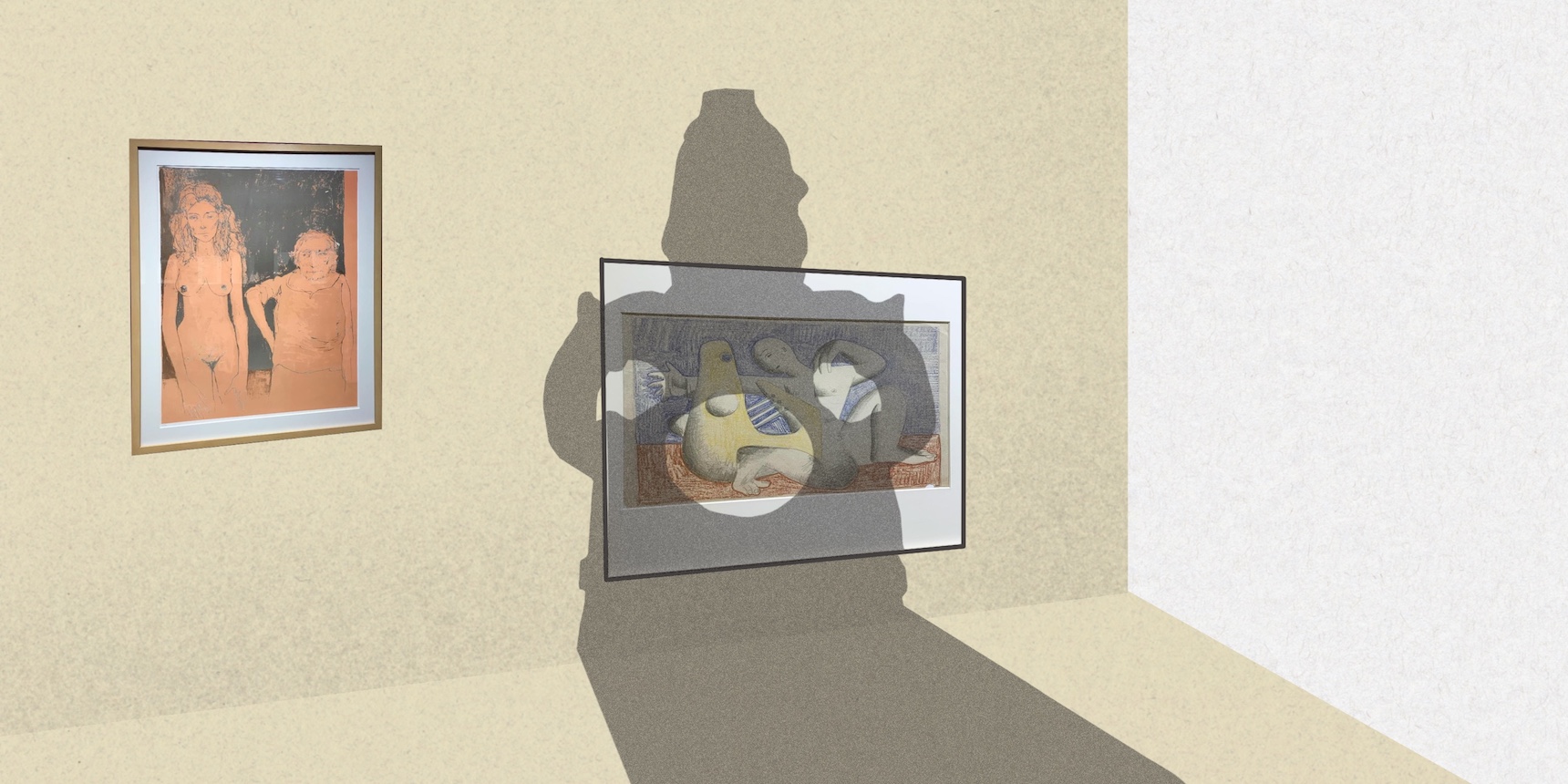

The March 2023 exhibition “The Guises of the Nude: Perceptions of Nudity in Armenian Graphic Arts,” at the National Gallery of Armenia, curated by Vigen Galstyan and Seda Khanjyan, challenges traditional art-historical narratives by exploring the multifaceted representations of nudity in Armenian art of the modern era. Featuring over 100 examples of graphic art from the 1850s to the present day, the exhibition showcases the enduring presence of the nude throughout Armenian art history. It examines the role of the body in global modernism, Armenian avant-garde art, and post-independence contemporary works, offering diverse representational approaches and inviting viewers to contemplate the interplay between aesthetics, politics, and social transformation.

The thematic exhibition presents its subjects in a variety of cultural, social and political contexts, inviting viewers to critically examine the non-linear trajectory of Armenian art. The trajectory fluctuates between Eastern Christian traditions and the pervasive influence of the Western artistic canon. Organized into seven sections, each explores the dualistic nature of the nude and gently probes the political implications behind representations of the body. Thus, eroticism is presented through a critical prism that targets gender norms, Orientalism, and the male gaze in Armenian art. The exhibition also highlights the significance of feminist, queer, and decolonial perspectives in the sections devoted to formalism and contemporary art.

Within this framework, nudity in modern Armenian art serves as a medium for exploring broader discourses on nationalism, utopian socialism, and the complexities of historical identity and cultural difference. Over the past two centuries, Armenian artists grappled with power dynamics, cultural hegemony, and the influence of both imperialist and socialist legacies as they embarked on the ambivalent search for “individual” artistic vision. By challenging established narratives, they fostered a more emancipatory understanding of their cultural heritage, while also deepening some of the contradictions inherent in their embrace of Western modes of visual art.

This exhibition focuses solely on works on paper and reveals a spectrum of styles from realism to abstraction. It showcases the various ways in which artists have utilized nudity to express a surprising gamut of artistic and conceptual ideas. Additionally, the exhibition highlights the often-overlooked contributions of Armenian graphic artists, demonstrating the potency of graphic arts in conveying more intimate and nuanced messages.

The curators conducted extensive research to identify significant artworks from the gallery’s collection. These works exemplify the dominant critical, thematic and theoretical interests that have preoccupied Armenian artists in Armenia and the diaspora. The exhibition also emphasizes the role of nudity in stimulating formal and conceptual inquiries into human beliefs, sexuality, imagination, and socio-cultural reality. Furthermore, the show illustrates how nudity has evolved in contemporary Armenian art, serving not merely as a representation of desire, but also as a vital tool for acknowledging and validating diverse perspectives on the ever-changing social, sexual, and cultural experiences of human existence.

By highlighting the relationships between Western-centric influences, Orientalism, and the power dynamics of the male gaze, the exhibition exposes the political ambiguities that come with depicting the nude in Armenian art. “The Guises of the Nude” thus provides a powerful opportunity to challenge prevailing meta-narratives and foster a self-reflective dialogue that can contribute to the broader project of decolonization and social transformation.

Unveiling the “Guises of the Nude”

The exhibition is organized into thematic sections, including “The Classical Ideal”, “Realist Visions”, “Under the Sign of Eros”, “Tradition and Trauma”, “A Language of Forms”, “Metaphor Machine,” and “Shame/less”. These sections highlight the dualistic nature of nudity in art and explore the distinction between the “nude” as an object of aesthetic admiration and “nakedness” as a term with broader social connotations.

The portrayal of nakedness in art and literature reinforced colonial power structures and perpetuated racial stereotypes. In her 2008 book, “States of Undress: Nakedness and the Colonial Imagination”, Philippa Levine argues that showing non-European subjects in various states of undress helped forge an image of the “primitive other”, further justifying the colonial mission. Clothing also delineated social status and cultural differences, highlighting how the colonial imagination exploited nakedness to retain control and domination over colonized populations.

The Armenian art scene of the mid-19th century underwent a shift toward the Western European academic canon. This transformation warrants a critical appraisal of power distribution and exercise in art critical discourse. Garegin Levonyan’s Gegharvest (Fine Art) magazine embodies the apogee of this transformation. By publishing articles relating to European aesthetics, the magazine facilitated cross-cultural dialogue, enriching artistic expression. However, it also perpetuated Eurocentric hegemony in local arts.

As Vigen Galstyan noted in his curatorial talk, Levonyan’s magazine reproduced academic, kitsch images emblematic of high art, frequently portraying the human body as a flawless, idealized and “white” form. This style of representation reveals a specific understanding of beauty and artistic merit rooted in Western aesthetic traditions.

Consequently, it is crucial to examine how this approach reinforced existing hierarchies and excluded alternative perspectives. The enduring influence of Greco-Roman art on Western European artistic traditions often prioritized the idealization and objectification of the human form, which can be perceived as a product of hegemonic power relations pervading the global art world. The show’s most revelatory aspect is Knarik Vardanyan’s previously unexhibited nude self-portraits from the 1960s. By presenting them, the curators introduce viewpoints that defy these norms and encourage viewers to question the canonized artistic gaze in relation to the emancipatory approaches to the nude developed by female artists.

The section “Under the Sign of Eros” takes a deeper look at the volatile issue of eroticism in Armenian art. It explores societal views of women as irrational and subordinate to men, as well as the potential of eroticism to challenge and subvert dominant social norms. This section sheds light on the objectification of the female body, the impact of orientalization, and the implications of shame within the artistic realm. By doing so, it offers a critical review of how these factors have contributed to the perpetuation of stereotypes and the reinforcement of patriarchal and colonialist attitudes.

Mher Abeghyan’s work exemplifies the multifaceted influences shaping the depiction of the eroticized nude body in Armenian art. It demonstrates the complex relationship between national modernism, socialist realism, and the resurgence of the Western European art canon during Khrushchev’s Thaw. Nevertheless, Abeghyan’s work also reflects the hegemonic power dynamics that informed artistic representations of nudity. Themes of motherhood and family act as “cultural alibis” that reveal societal expectations and certain moralistic predispositions.

Similarly, the 1920s etching “Abandoned Ariadne” by French-Armenian Tigrane Polat represents the apotheosis of women’s objectification in European art. It employs a classical format similar to renowned nudes by Titian and Rubens. By prioritizing the portrayal of the female body for sexual arousal, rather than empathizing with the woman’s suffering, Polat’s work, along with others by the likes of Vardges Surenyants, continued to entrench this objectified stereotype in the annals of modern Armenian art.

Orientalism, the system of representing and depicting the East as a collective, symbolic, and ahistorical phenomenon devoid of identity or agency, has significantly influenced Armenian art. This has led to the proliferation of odalisques and exoticized representations of women that reinforced patriarchal and colonialist attitudes.

However, some artists like Alexander Bazhbeuk-Melikyan present a world of distinctly feminine sensuality and eroticism that defies binary understandings of the patriarchal or “male gaze” in Armenian art. It is crucial to acknowledge the impact of colonialism and capitalism on local artistic practices, as the exhibition makes patently clear. For example, the association of the (female) body with natural forces in Armenian art often reinforces the destructive idea that women primarily exist as reproductive mechanisms under male guidance.

Analyzing how these gender tropes and patriarchal structures have influenced artistic representations and how Armenian artists have challenged these conventions is essential. Notably, Aytsemnik Urartu, a female sculptor, defies the male gaze with her full-figured portrayals of women, reclaiming bodily autonomy and challenging beauty standards. Her critical perspective contributes to a deeper understanding of individual artistic resistance to pervasive narratives and structures.

In the section “Language of Forms”, the curators elaborate the body’s role as material for aesthetic exploration, particularly in global modernism. Here, the body is transformed from mere subject matter to a vehicle for formal experimentation, illustrating the interplay between cultural and technological forces. Modernist art has been shaped through a dialectical tension between progress and critique, vacillating between an infatuation with scientific and industrial advances and a critical stance towards the imperialistic and homogenizing tendencies they embody. Armenian artists, influenced by this dichotomy, adopted diverse artistic approaches that questioned Eurocentric narratives and engaged with their heritage. This dynamic interplay is exemplified in Gevorg Grigoryan’s (aka Giotto’s) art, which reflects an interpolation of modernist styles like cubism with the archaic forms of Armenian medieval iconography.

The “Metaphor Machine” section further develops these threads, which highlights the complex dynamics between Armenian art and the global artistic milieu from the 1920s to the 1970s. By examining the works of French-Armenian avant-gardists Yervand Kochar and Petros Kontrajyan, we can see fascinating tensions between academic tradition, modernity, and technology’s role in shaping artistic expression. These divergent artists’ oeuvre demonstrates modern Armenian art’s multipolarity and heterogeneity, inviting us to consider how artistic practices negotiate complexities of identity, memory, and historical trauma. For instance, Khoren Ter-Harutyunyan’s focus on the Armenian Genocide exemplifies art’s potential to bear witness, while Jean Carzou’s work critiques modernity as a destructive force. The avant-garde propositions of Kochar and Kontrajyan challenge conventional perceptions of Armenian modernism, but it is essential to consider their broader implications and how they might reproduce or resist capitalist modernity. The selected works in the exposition do not provide a definite answer but instead open a dialogue on the heterogeneous nature of Armenian modernist art and its uneasy oscillations between tradition and progress, “national” narratives and globalist paradigms.

The final exhibition section, “Shame/less”, showcases largely post-independence contemporary works. It features artists who had greater freedom to explore the body as a tool for critical thinking and expression. The exposition makes broad connections between established classics of Armenian modernism, such as Hripsime Simonyan and Hakob Gurjian, and living artists like Nana Aramyan, Levon Fljyan and Arman Grigoryan. These artists employ the naked body as a site of resistance and symbol of art’s anti-establishment stance.

Hripsime Simonyan’s 1960s drawing “Lovers” comes as a bold exploration of women’s empowerment, female desire, and sexuality. It subverts traditional power dynamics in romantic relationships, reflecting an emancipatory impulse challenging patriarchal norms. Fljyan’s “Pixels” series questions the heteronormative binary, literally blurring and destabilizing conventional gender notions. These works testify to the fact that Armenian artists have continuously used their practice as a means to challenge dominant ideologies and inspire social transformation long before such freedoms were allowed after the post-independence reforms.

Nudity in Armenian Art: A Fluid Motif in a Changing Landscape

The motif of nudity in Armenian art has been the subject of debate and scrutiny for centuries. It is a theme that has been revisited time and time again throughout Armenian art history. It was frequently incorporated into Bronze and Iron-Age ceramics, to its resurgence in modern Armenian painting in the mid-19th century.

During the ancient period, nudity was often depicted in mytho-poetic forms that signified collective beliefs and holistic perceptions of human sexuality. However, during the early medieval era, the strict moralist codes of the Christian doctrine led to an almost complete disappearance of nudity in Armenian art until the dramatic shift to Western norms of visual culture in the 1830s.

With the onset of the socialist era in Armenia, nudity as a subject was encouraged, but largely as a means of promoting the socialist ideal of physical power. However, despite the state’s rigid guidelines, many artists found ways to subtly bypass such restrictions, paving the way for greater artistic freedom in the post-socialist era.

During and after the Thaw period, Soviet-Armenian art underwent a fundamental transformation, with nudity becoming a more prominent theme. According to Galstyan, nakedness was viewed as a symbol of humanism with spiritual undertones and ecocentric patriotism during this time. He notes that the depiction of nudity was perceived as a means of liberating art from its political frameworks, as if stripping the body of clothing was equivalent to “cleansing” art from its ideological veneer.

After Armenia gained independence in 1991, there seemed to be no boundaries as to what local artists were able to represent and how, including nudity. An example of this is the 2010 exhibition “Body: New Visual Art in Armenia”, which featured over 50 works by 39 artists from different generations and disciplines. This exhibition showcased a variety of conceptual and formal strategies of international contemporary art, curated by artists Ararat Sargsyan, Sargis Hamalbashyan, Arevik Arevshatyan, Arman Grigoryan, and the late David Kareyan.

Despite the openness towards nudity in the art scene, it remains a highly controversial subject in Armenian society and mass culture, suggesting that unresolved complexes, fears and misunderstandings are still prevalent.

Unveiling the Layers of Critique

A concise examination of the exhibition provides valuable insight into the exploration of nudity in Armenian art. However, it also raises concerns about the institutionalization of nudity and the potential for perpetuating oppressive societal norms, contributing to body shaming and low self-esteem among those who do not conform to these standards.

The commodification of the human body, particularly the female body, for artistic expression has long been criticized in Western academia for its exploitative tendencies. Recently, artist Lucine Talalyan posted a brief critique of the institutionalization of nudity on social media, echoing the concerns of many international scholars and critics. As mentioned earlier, the exhibition includes a dedicated section addressing this issue, emphasizing the importance of examining and challenging such practices in art.

Institutionalized nudity has faced scrutiny for its exclusionary nature, with women underrepresented in the creation, curation, and critique of the naked body in art. This limited representation has resulted in stereotypical depictions of the female form, neglecting the diverse range of body types and experiences. The objectification and idealization of the female body in art can be traced back to Laura Mulvey’s “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” (1975), which introduced the concept of the male gaze in visual media. John Berger’s “Ways of Seeing” (1972) also criticized the idealized representation of the female body in Western art and its perpetuation of European (White) beauty standards. Griselda Pollock’s “Vision and Difference: Femininity, Feminism, and the Histories of Art” (1988) examined the exclusion of women artists and the representation of the female body in art history. Edward Said’s “Orientalism” (1978) critiqued the West’s representation of the East as exotic and other, which has been relevant in discussions of nudity in non-Western art. Judith Butler’s “Gender Trouble” (1990) introduced the concept of gender performativity and the fluidity of identity, which has also strongly informed critiques of the nude.

In the context of Armenian art, cultural critic Hrach Bayadyan’s essay “The Naked Body and the National Landscape” provides valuable insight into the role of nudity in Armenian visual culture, its relationship to politics, and the representation of women. This text is particularly enlightening in its analysis of the search for a “national style”, in which the body plays a central role. Bayadyan argues that the female body has been appropriated by the national landscape in Armenian art, in accordance with the emergence of nation-states and the construction of cultural identity. Orientalism has also had a strong influence on Armenian painting, but attempts to overcome it were seen as cultural resistance. Bayadyan applies Said’s concept of Orientalism to painting, revealing the perpetuation of stereotypes about women and non-white races. According to the author, Orientalism remains sadly relevant in discussions of Armenian identity, and the re-Orientalization tendency in Armenia highlights the ongoing effects of colonization and imperialism on art and culture.

The importance of challenging problematic representations in art cannot be overstated. However, Armenian art institutions have been lagging behind in this matter. “The Guises of the Nude” exhibition takes an important step in addressing these issues. One way it does this is by placing a self-portrait by a female artist alongside academic figure studies of idealized body norms. This highlights the political nature of the topic. The exhibition’s thematic structure further emphasizes this framing. centering around critical and theoretical matters related to the representation of the body in art.

By confronting problematic representations head-on, art institutions can initiate discussions that can lead to a deeper appreciation of the historical and cultural contexts that have given rise to harmful tendencies. Moreover, by presenting such works within a critical framework, art institutions provide alternative readings of historical artworks, contributing to the larger project of social transformation. In this vein, “The Guises of the Nude” invites us to consider the complexity of meanings and contexts that the representation of nudity in art embodies. The curators emphasize that the Nude is not a simple or static aesthetic category, but rather a complex interplay of cultural norms, values, and power dynamics. Drawing upon social constructivism, we can better understand how social and cultural factors influence our perceptions of nudity in art. However, by engaging with the ideas of Feminist New Materialists such as Karen Barad, Rosi Braidotti, and Elizabeth Grosz, the exhibition could have further explored the material dimensions of this interplay, examining the role of the human body, artistic materials, and exhibition spaces in shaping our understanding of the nude.

In this context, it is essential to consider the National Art Gallery of Armenia’s impact on the construction of Armenian art history. The gallery’s collection and archiving policies run the risk of limiting the richness and diversity of Armenian artistic expression by excluding works considered too provocative or obscene. Furthermore, the absence of groundbreaking female artists such as Arax Nerkaryan, Astghik Melkonyan, and Lucine Talalyan in its holdings narrows the institutional narrative and overlooks vital perspectives on the representation of female nudity that engage with complex socio-cultural and political issues.

As critical observers of the art world, it is our responsibility to scrutinize the decision-making processes governing the acquisition and curation of artworks in museums and galleries. In the context of Armenian art, we must question the criteria used to select works for inclusion in collections and advocate for a more inclusive approach that recognizes the diverse and multifaceted artistic expressions within the country.

The exhibition’s curators have taken steps in this direction by acquiring works by female artists such as Hripsime Simonyan, Teni Vardanyan and Nana Aramyan and showcasing previously unexhibited pieces by Knarik Vardanyan, Aytsemnik Urartu and others. By embracing inclusivity in art collection and curation, we can expand our understanding of Armenian art and challenge the dominance of narrow nationalist and patriarchal narratives that exclude crucial voices and perspectives.

Unveiling the Layers of Decolonial Discourse

The exhibition, which centers on Armenian perspectives of the nude, must be understood within wider power dynamics. It is necessary to examine its ties to decolonial efforts as a multifaceted, ongoing political and discursive practice for change. Decolonization, as described by George J. Sefa Dei, involves reclaiming cultural, historical, and spiritual ontologies lost in the colonial past. This process also involves embracing resistance and advocating for new forms of collective participation.

This transformative journey toward a more equitable future necessitates critical reflection on the prevailing structures and narratives within the art world. It involves contesting Western-centric viewpoints and nurturing diverse epistemologies. Additionally, it requires addressing intricate intersections of class, race, and coloniality, and confronting the racial capitalist system perpetuating exploitation and inequality.

Although interconnected, anti-colonialism and decoloniality are distinct projects. Anti-colonialism aims to liberate nations by targeting the political and economic systems of colonialism, whereas decoloniality focuses on dismantling knowledge systems and cultural hegemony perpetuated by colonialism. Decoloniality, thus, refers to the process of deconstructing lingering colonial power structures and knowledge systems that persist beyond formal colonial rule.

In her early work, Madina Tlostanova characterizes the post-Soviet condition as one of displacement and hybridity, shaped by the legacies of Soviet socialism and the resurgence of national identities. This results in the coexistence of colonial and anti-colonial elements within the post-socialist experience. Moreover, Tlostanova argues that global colonial power structures persist, rendering the post-Soviet region both a victim and a perpetrator of global coloniality. Acknowledging the distinctiveness of post-socialist experiences is crucial for a nuanced understanding of the complexities involved.

Angela Harutyunyan’s critical analysis of decolonial discourse highlights the necessity of examining historical context when engaging with such theories. In the Soviet context, Harutyunyan suggests that decolonial discourses may oversimplify the intricate and often contradictory nature of the Soviet past, disregarding its anti-colonial struggles and the legacy it left behind. It is important to recognize that the Soviet Union played a critical role in anti-colonial movements, particularly in the Global South. Therefore, a simplistic understanding of Soviet history that fails to acknowledge these complexities can do a disservice to the anti-colonial struggles that took place during this period.

In response to these critiques, the exhibition curators take a deliberate and analytical approach towards the discourse of decolonization, eschewing an apolitical stance. The inclusion of diasporan artists alongside Soviet-Armenian ones underlines the complexities of defining 20th century Armenian art within geopolitical and hierarchical frameworks. This strategy enables the curators to delve more deeply into the intricacies of art, culture, and society, avoiding the reduction of complex historical experiences to simplistic or binary terms. In doing so, they move towards a more comprehensive and diverse art history that interrogates dominant narratives, dismantles the remnants of colonialism, and elevates underrepresented perspectives.

“The Guises of the Nude” heeds Grant and Price’s call for decolonizing art history by transforming content and methodologies to encompass diverse perspectives and foster inclusivity. The exhibition showcases historical formulations of nudity in Armenian graphic arts, acknowledging global contributions, confronting imperialist ideologies, and championing artistic diversity. It provides insights into Armenian cultural history, invites reevaluation of cultural narratives surrounding the naked body, and encourages the exploration of alternative, inclusive histories.

Nudity in Armenian art serves as both a political and cultural pivot, reflecting forces that shape artistic creation. Through its synthesis of global and local art forms, socialist avant-garde traditions, and Eastern Christian pictorial legacy, it contests dominant aesthetic, ethical, and political norms, undermining the impact of colonialism and imperialism. The exhibition underscores the ongoing struggle for cultural emancipation and the urgency of decolonization efforts in the pursuit of cultural liberation.

References:

Bayadyan, H. (2010). The naked body and the national landscape. Hetq.am.

Berger, J. (1972). Ways of seeing. British Broadcasting Corporation and Penguin Books.

Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham: Duke University Press.

Braidotti, R. (2013). The Posthuman. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Dei, G. J. S. (2019). Foreword. In A. Zainub (Ed.), Decolonization and Anti-colonial Praxis (pp. vii-x). Anti-colonial Educational Perspectives for Transformative Change, Vol. 8. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill.

Galstyan, V. and Khanjyan, S. (2023). The Guises of the Nude: Perceptions of Nudity in Armenian Graphic Arts [Exhibition]. National Gallery of Armenia.

Gandhi, M. (1997). Gandhi:’Hind Swaraj’and Other Writings. Cambridge University Press.

Geerts, E., & Carstens, D. (2019). Ethico-onto-epistemology. Philosophy today, 63(4), 915-925.

Gerstle, C. A., & Milner, A. (Eds.). (1995). Recovering the Orient: artists, scholars, appropriations (Vol. 11). Psychology Press.

Grant, C., & Price, D. (2020). Decolonizing art history. Art History, 43(1), 8-66.

Green, S., McInherny, A., Orchard, C., Randell-Moon, H., & Jeffries, P. (2020, November). The role of art in colonisation and decolonisation. In Artstate Wagga Wagga 2020.Grosz, E. (1994). Volatile Bodies: Toward a Corporeal Feminism. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Harutyunyan, A. (2019). Opting for Decoloniality: A Politics of Non-Politics. Art History, 42(5), 996-1000.

Loomba, A. (1998). Colonialism/postcolonialism (Vol. 178). London: Routledge.

Mabasa, K. (2021). Racial capitalism: Marxism and decolonial politics. In Marxism and Decolonization in the 21st Century (pp. 228-247). Routledge.

Mignolo, W. D. (2007). Delinking: The rhetoric of modernity, the logic of coloniality and the grammar of de-coloniality. Cultural studies, 21(2-3), 449-514.

Mignolo, W. D., & Walsh, C. E. (2018). On decoloniality: Concepts, analytics, praxis. Duke University Press.

Mulvey, L. (1975). Visual pleasure and narrative cinema. Screen, 16(3), 6-18.

Ndlovu‐Gatsheni, S. J. (2015). Decoloniality as the future of Africa. History Compass, 13(10), 485-496.

Pollock, G. (1988). Vision and difference: Femininity, feminism, and the histories of art. Routledge.

Rodney, W. (2022). Decolonial Marxism: Essays from the Pan-African Revolution. Verso Books.

Said, E. W. (1978). Orientalism. Pantheon Books.

Tlostanova, M. (2012). Postsocialist≠ postcolonial? On post-Soviet imaginary and global coloniality. Journal of postcolonial writing, 48(2), 130-142.

Tlostanova, M. (2018). What does it mean to be Post-Soviet?: Decolonial art from the ruins of the Soviet empire. Duke University Press.

Et Cetera

The Regional Policies of the Cannes Film Festival

Major film festivals don’t only showcase films for local and international cinephiles, they also create opportunities for unknown stories, names and voices to be heard. Sona Karapoghosyan writes about how the Cannes Film Festival is trying to tell the stories of everyone, not only ones from the West.

Read moreLiving Portals: Reflections on Territorialization in Contemporary Armenian Art

A review of an exhibition in the village of Verishen in Armenia’s Syunik region featuring a contemporary carpet collection by Goris-born artist Davit Kochunts, examines the concept of social space and the process of territorialization.

Read moreDon Quixote: Present and Absent in Armenian

The Armenian translation of Cervantes’“Don Quixote” has not yet reached readers, despite being a masterpiece of world literature. Aram Pachyan delves into the reason behind this.

Read moreA Vision of Power: The Royal Crowns of Cilicia

Crowns worn by monarchs reveal stories of hierarchy and power, providing insight not only to those who wore them, but the strata to which they belonged. Margarita Ghazaryan looks at the story of the royal crowns of the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia.

Read moreArt as a Tool for Conflict Transformation and Healing War Trauma

Art can be an effective tool of conflict transformation impacting societal attitudes and perceptions by producing a cathartic effect on both artists and audiences, writes Anna Kamay.

Read moreLove and [un]Love in “The Miracle Worker”

Nune Hakhverdyan reviews the Armenian production of “The Miracle Worker” staged by the Gyumri Drama Theater and Yerevan’s Hamazkayin Theater about the life of Helen Keller, and examines the relationship between parent and child.

Read moreExhibition Outside of the Traditional Art Space

In Armenia, there are few exhibitions outside of the traditional art space environment, but at the same time, one can notice distinctive new trends emerging in recent years.

Read moreGraphic novel

Mother Armenia

Hayasdan (Armenia) is a graphic essay that explores the relationship between contemporary Yerevan and its past. The work, by Harut Tumaghyan and Armen of Armenia (Ohanyan), is divided into three parts, each delving into the city’s socio-political and cultural context from an urban perspective.

Read moreArts & Culture

Arev’s Brezhnev Years

“A murderer could get amnesty, but not people like me. Bribery was considered the worst thing, although during Brezhnev's time bribery was everywhere, widespread and first of all in his own system…”

Read moreThe Rise of Armenia’s Colorful Twisty Puzzle Community

Although it was initially created to teach mathematical concepts 50 years ago, today, people have turned the Rubik’s Cube into a competitive sport called speedcubing. Armenia is now part of that world and holds several records.

Read moreTrue But Not Real Stories

The Peephole

A peephole view into the kaleidoscopic distortions of other people’s lives where human interaction is set in ways foreign to you and distant from you yet in your city where the “hero” is your friend. A true, but not a real story from the ninth floor, in building 9a, in the Ninth District, the door without the peephole.

Read moreHouse of Horror

In this “True But Not Real Story” the Verdyans are unperturbed that the house they are buying is known to be possessed by ghosts and evil spirits.

Read moreHomekeeping

"Not a True Story But a Real Story" series is a reflection on individual transformations of collective identity and the concept of home. Armen of Armenia (Ohanyan) ponders why “housecat-like Armenians” didn’t just sit tight within their four walls when they could have become “heroes” by simply staying home.

Read moreZarmanazan

This is neither a true story nor a real story. But it could be either if fate ever stepped in to deliver a surprising lesson on toxic masculinity.

Read moreThe Quilted Refuge

A story weaving together the fragments of a woman’s life who organized the chaos of reality into a sensible and livable realm offhandedly called “home” but no one recognized it until she was gone.

Read more