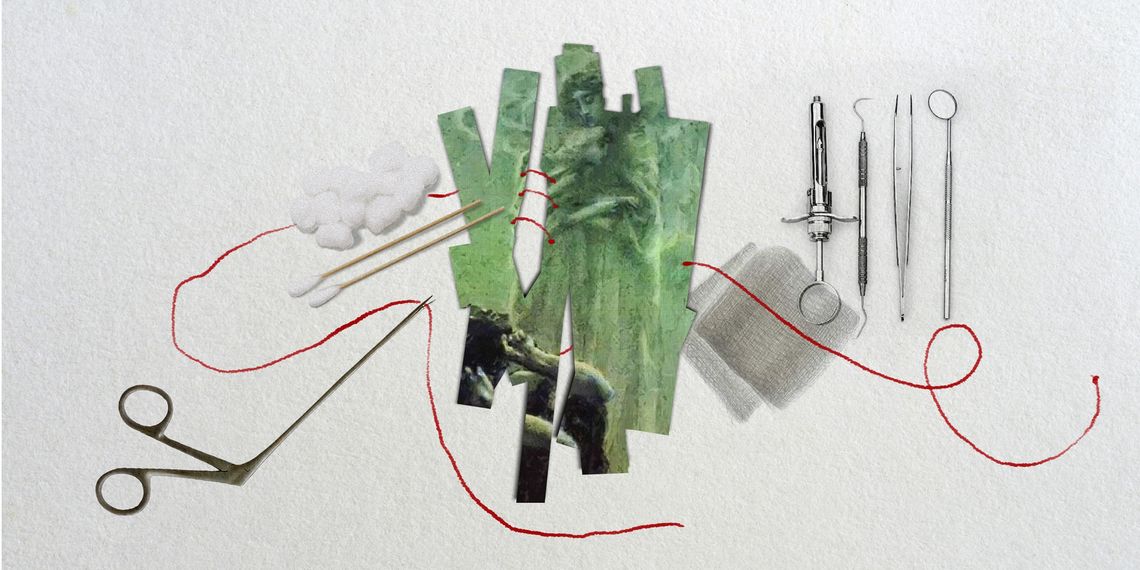

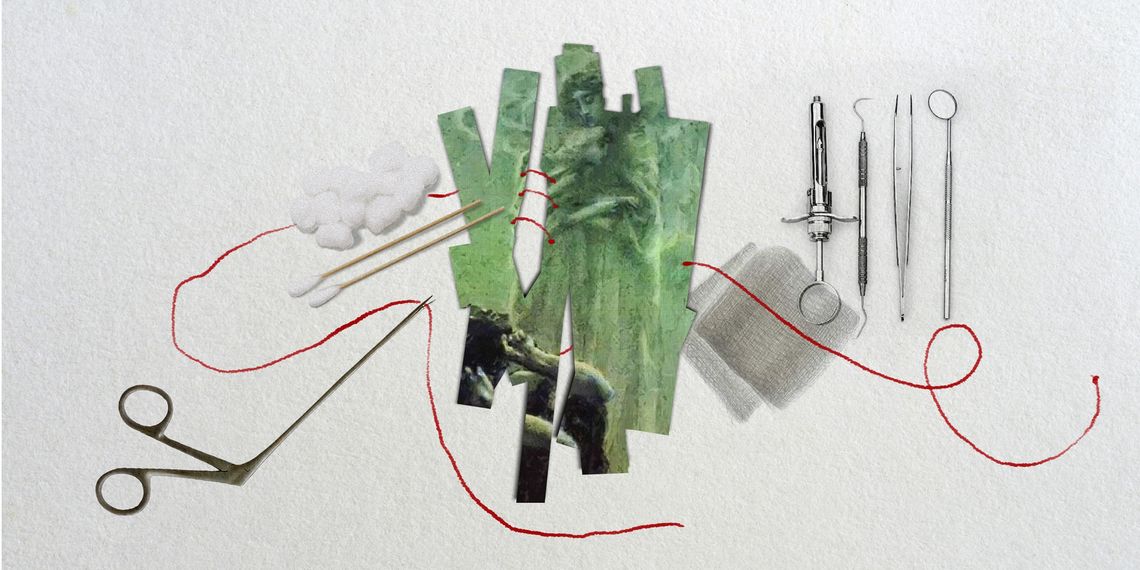

Illustration by Armine Shahbazyan.

Art restoration and conservation work is a relatively modern profession that is tied to the emergence of the first public and private museums in the 18th century. Though people have always taken care to preserve and restore objects and things of special significance, modern art conservation goes beyond preservation as it often asks ethical questions about how we should frame the histories of these objects.

Possessions tell stories of those who possessed them and our belongings are usually examined in detail after our passing to reveal untold stories embedded within the layers of dust and grime. These personal narratives are also representative of eras and of cultures that are now long gone, something that art conservation – when done properly – can bring to light and put into appropriate context.

Thus, particular attention is paid to the conservation of objects of collective significance such as paintings, manuscripts, certain books and other objects of similar importance, as they help to construct and perpetuate a national narrative. The process of conservation and restoration is critical in this regard, as it can unveil or wipe away information of considerable importance embedded in historical objects undergoing the process.

Regardless of our vociferous claims of cultural superiority and the importance of heritage for the national narrative in Armenia, the on-the-ground reality reveals a dire indifference towards the profession, its working conditions, financial inadequacies, and lack of proper training possibilities. The aim of this article is to examine the dissonance between the importance we ascribe to national values like cultural heritage and the less-than enviable conditions surrounding the profession of the “heritage doctors” in Armenia. It must be said, however, that this is in no way meant to undermine the great efforts of the restorers who do their very best in the unconducive environment of their chosen field. A restorer’s work in Armenia is a selfless act of commitment towards centuries of Armenian patrimony and a dedication to its protection and conservation.

(In)Auspicious Beginnings

The State Museum of Armenia was founded in 1921, just months after the newly-established Soviet Armenian Republic. One of the main and fastest-growing sections of the Museum was the Fine Arts department, which would become an independent institution in the early 1930s – currently the National Gallery of Armenia (NGA). However, it was only in 1933, that the Gallery began to employ artist-restorers, who both copied paintings and carried out restoration and conservation works. It can be claimed that the first art restorer at the NGA (and Armenia) was Vrtanes Akhikyan, an alumni of the Saint-Petersburg Academy of Art, who mentions holding the position in 1933, in his autobiography [1]. From the mid-1930s to the late 1950s, the restoration lab at the Gallery was spearheaded by a succession of other artist-restorers, such as Simon Galstyan, Hakobjan Gharibjanyan and Vardges Baghdasaryan. The latter received his professional training at Moscow’s Grabar Art Conservation Center in 1946 and led the Gallery’s restoration department for the following four decades. A particularly esteemed restorer during this period was the theatre painter Arman Vardanyan, who conducted a number of outstanding restorations on fragile Western European paintings.

The conditions for restoration work at the Gallery improved significantly when it relocated to its new building at the beginning of the 1970s. It became possible to carry out restorative tasks more efficiently than when the department lacked sufficient space and facilities to execute larger and more complex projects.

Following Armenia’s independence in 1991, the restoration department expanded with new specialized sections, in spite of the considerable financial limitations engendered by the post-Independence economic collapse. Despite the significant challenges, the Gallery’s restoration team has continued to build on the expertise and technical improvement through international training programs and technical assistance from foreign governments, such as Japan and Italy. Currently, there are seven restorers employed by the department – the second-largest such unit after the Matenadaran Institute of Ancient Manuscripts.

The restorers who were employed by the department were mostly painters, which established a tendency of employing artists as restorers who did not undergo extensive professional training for their profession․ As a result, fine art restoration as a separate profession remains neglected and the restorers insufficiently trained in Armenia. Though many of the current practitioners had their training in Moscow, this experience was brief in comparison to the years of education and apprenticeship that museum restorers undergo in Europe and America before they are tasked with any complex restoration jobs. At present, there are no University-based degrees in restoration and museum object care in Armenia, which hinders the possibility of a structured career path for potential candidates wishing to pursue this occupation. Yet, attitudes might be shifting, as indicated by a recent exhibition at the National Gallery, which took the profession out of the shadows and placed it in full view of the museum-going public.

Exhibiting Restoration at the National Gallery of Armenia

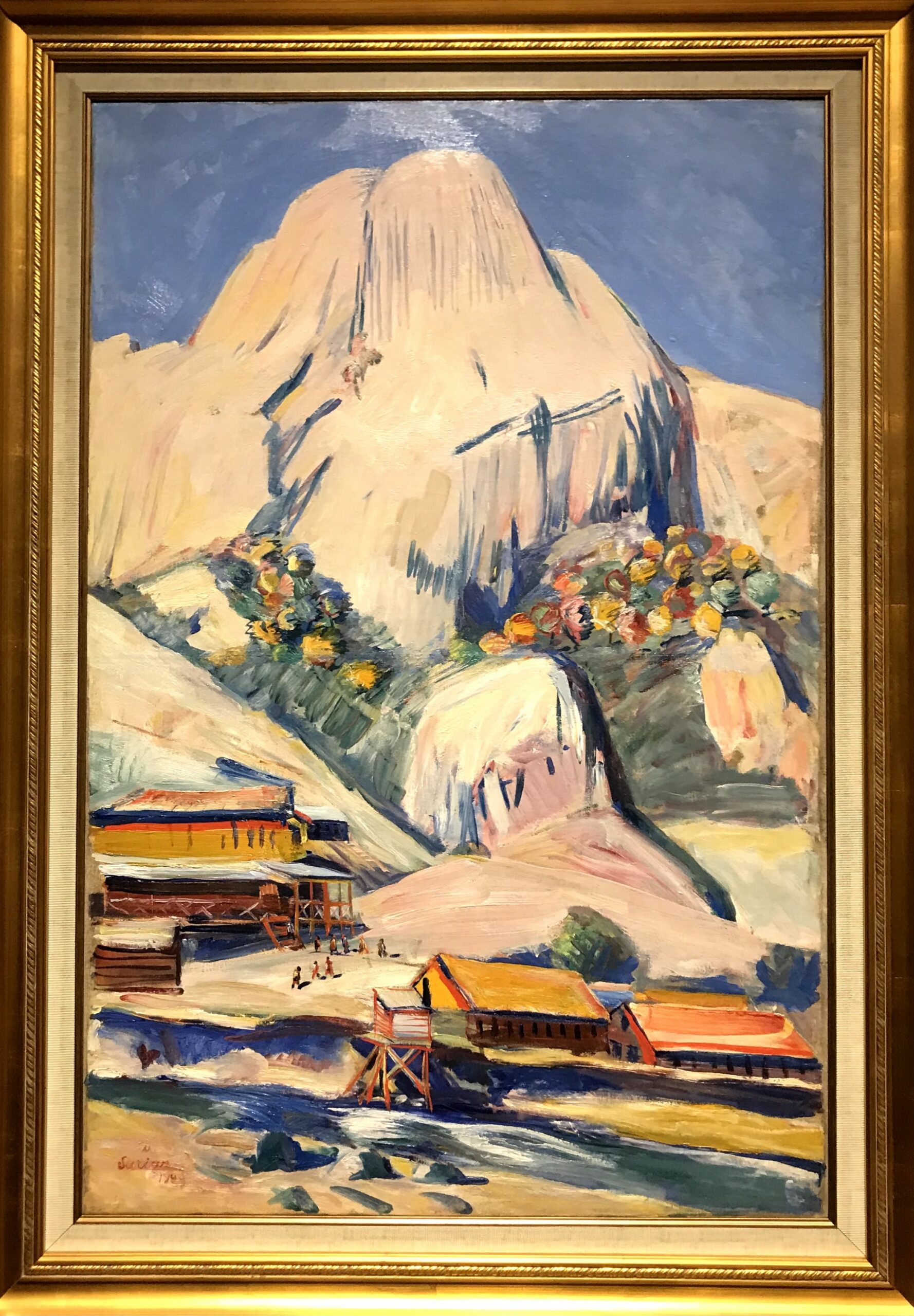

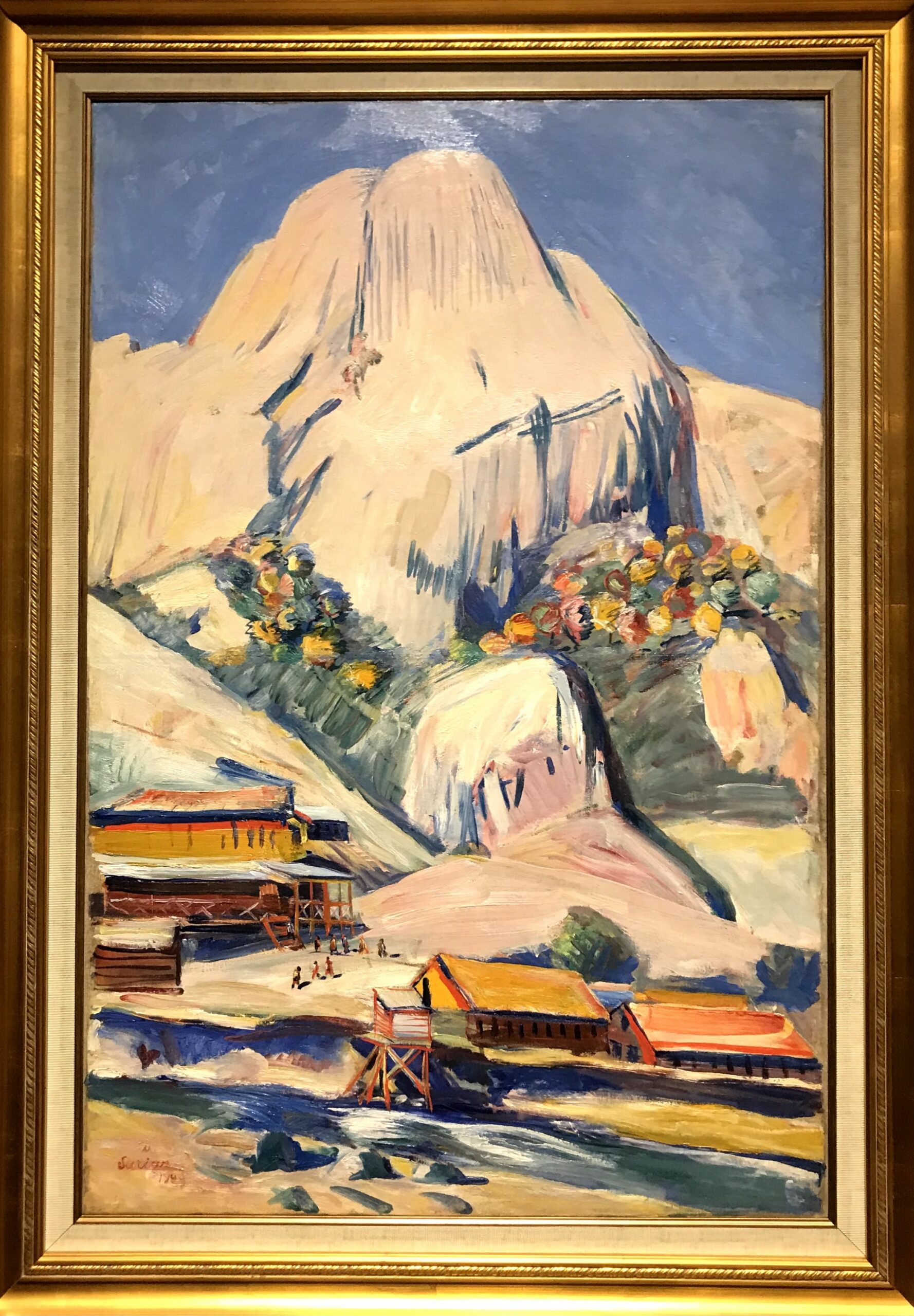

On May 19, 2021, the National Gallery of Armenia held the exhibition Art or Science: The Story of Three Restored Paintings. The exhibition was the first of its kind in Armenia and brought much-needed public attention to the intricacies of the restoration processes. The restored paintings were by three of the most prominent Armenian artists: Martiros Saryan, Hakob Kojoyan and Gevorg Bashinjaghian. A group of staff restorers from the National Gallery worked on the paintings for over a year. A corner in the exhibition galleries was used to showcase the restorers at work on other paintings and art objects. Another table showcased some of the technology used for identifying the layers of the paintings and assessing the type of conservation work needed.

Among the exhibits, Saryan’s painting had undergone the most restoration work and Tatevik Amirxanyan and Artashesh Abrahamyan, who were responsible for the final result, shared some insight into their methods and some of the issues they faced during the restoration process. The piece had come to the Gallery in a badly damaged condition, which required complex and careful intervention. Saryan made the painting by attaching two separate canvases together, which caused some complications, such as a deformation of the canvas and the deterioration of the paint. The restorer’s task, thus, involved a tedious process of detaching and resetting the two pieces back without creating any further paint loss. Grime was removed, lost and cracked sections in the paint were filled-in and the line connecting the two canvases was concealed with retouching.

The results were impressive, as the once faded colors came to life with vibrancy and astonishing freshness. And yet, this was exactly what disturbed me in my initial impressions of the work. The restoration seemed too good, overdone even, as the restorers appeared to approach the task mainly from a technical standpoint, without considering the importance of traces that speak of the historical narratives of the object. While the purpose of restoration and conservation seems obvious, there is a thin line that divides conservation and the desire to “revive” an original state by eradicating all the wrinkles and scars acquired by the object throughout its lifetime.

Saryan’s Restored Painting (courtesy of the author).

It is clear that Saryan had the means to get a canvas of a proper size to execute his vertical landscape painting, nevertheless, he opted for an experiment. The process of restoration, however, carefully concealed the line with paint that attached the two bits together. In this particular case, the resultant painting was a clear example of the artist’s evolving style in the early 1930s, but also, equally, a fascinating testament of the artist’s creative processes, which the restoration “veiled” from the view for the sake of a more palatable, “holistic” image.

In general, local art restoration traditions—as evidenced by the many examples of earlier restorations on display at the National Gallery—tend to conceal and “touch up” the imperfections and damages suffered by the object during its biography, in order to exhibit a “perfected” version of what the object used to be. Hakob Kojoyan’s piece, in particular, was a distinct demonstration of this, as it was in “ideal” condition post-restoration. Patched up with fresh paint, it somehow felt unnaturally glossy and “brand–new” for a work made in the impoverished conditions of the 1920s Soviet-Armenian art scene, where good materials were hard to come by even for established artists like Kojoyan. A question, therefore, stands to be unanswered – what purposes and aspects is restoration work meant to serve, and how are these processes really helping us understand the artworks precisely as historical objects and not simply as “timeless” pieces of decontextualized aesthetic pleasure?

Ethical approaches vary as different cultures have diverging understandings of what restored objects should “do”. The restorer of paintings at the Vanadzor Museum of Art, Arpine Hovhannisyan, gave an overview of the accepted best practice standards in Armenia.

“[The general rule is that] we do not touch the painting when the picture is damaged to the point where possible figures are already affected and missing. In that case, we are not advised to fill in the artist’s layer, I do not know why. But we came to a common decision with our former director to restore [fill-in lost parts] of several works and as a result, these paintings are seen today in their original form. For example, the Russian school [accepts intervening with the painting and adding the missing figures and parts], but the Italian one forbids it. There are such contradictions, and in any case, we try to keep the artist’s layer as much as possible and fill in the rest so that it does not differ. If we don’t have an image of the painting in its original form or have any information on what the picture was like, but we have decided to add the lost parts, we do it by coming to a common conclusion, but [such practice] is usually not recommended.”

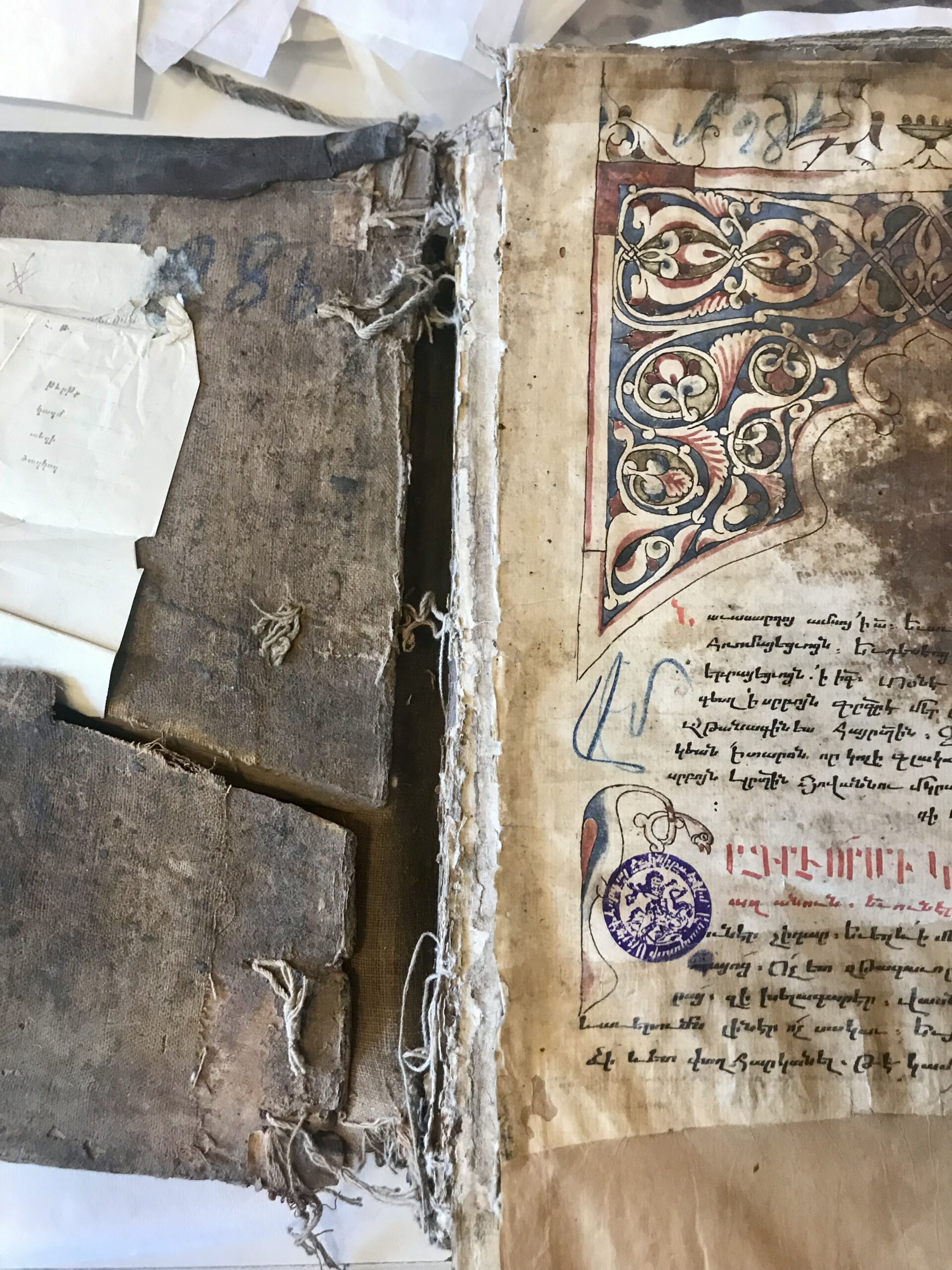

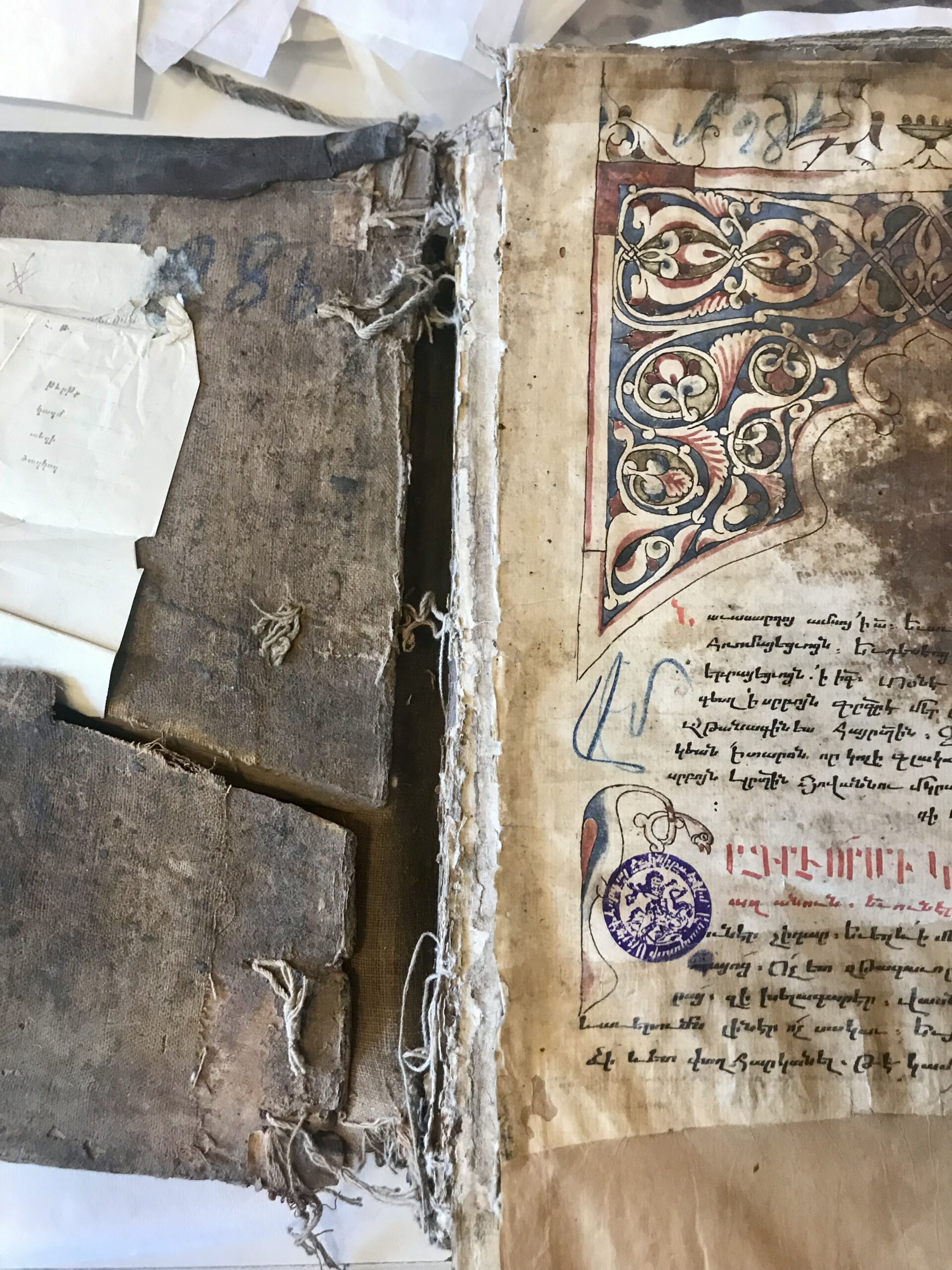

But this approach is quite common in Armenia regardless. A similar conversation was held with one of the restorers at Matenadaran who was working on a medieval book saved from a fire. The book’s spine was adequately preserved, however, the restorer’s goal was not to simply conserve the pages but to bring the book back to its former look. She also mentioned that such practices are criticized by the European restoration school. Nevertheless, the restorers prefer to recreate the original state and remove the traces of history’s intervention whenever possible.

Drawing parallels with the restored Saryan painting, it may be claimed in the case of this book as well, that the assignment perhaps should have been to conserve and prevent further deterioration, rather than to reconstruct the object’s complete original state. Another issue here is the question of reversibility. Attitudes to restoration have and will change dramatically over time, and modern restorers generally ensure that their work can be “reversed” (erased), in order to allow future generations full access to the extant original layers of the objects. In Armenia such an approach appears to be less common and it is not entirely clear how easily future Armenian restorers will be able to remove the work of their predecessors.[2] In all cases, the restorers agreed that the integrity of the work and its originality must be preserved, but when it comes to the ethics of adding and “finessing”, such notions are not discussed or debated about in professional circles, which is another unfortunate outcome of the lack of multifaceted training and rigorous institutional standards.

Untrained and Badly-Paid

One of the most fundamental obstacles for the development of the art restoration sphere in Armenia is the absence of higher education offering qualifications for restoration and conservation work. As mentioned above, most of the art resorters based in Armenia come from an artistic background and, if fortunate, receive limited training at Moscow’s Grabar Art Conservation Center. Those who wish to become part of the restoration team at the National Gallery have to undergo a probation period with the team that lasts three to six months.

Book Restoration at Matenadaran (courtesy of the author).

Restoration work requires skilled expertise and multidisciplinary knowledge in diverse fields such as chemistry, fine arts as well as art history and even ethics, but due to the absence of specialized educational courses in Armenia, the restorers receive inadequate training that is solely focused on technical skills. This often means that the restorer is insufficiently prepared to make an informed judgment regarding the extent of their intervention. The worst example of this, of course, is in architectural restoration, where crude interventions by ordinary stonemasons can irreparably alter the original state of the monuments through hypothetical reconstructions and the use of modern materials and technologies, such as sand-blasting and steel, as was the notorious case of the 9-13th century Garni Bridge.

Despite the very obvious importance of restoration practices for the maintenance of Armenian cultural heritage, the Education and Culture Ministry has never implemented any long-term programs to train a qualified army of specialists, essential for the preservation of the country’s enormous holdings of historical and art collections. Similarly, the indifference towards the sector is painfully exemplified by the lack of properly remunerated staff positions. For example, the Museum of Folk Art in Yerevan has just one restorer on its staff, who can conduct only very basic conservation work on one of the key national collections in the country.

The very idea that a single restorer could be held responsible for objects made from an array of fragile materials like textile, wood, glass and metal, is in itself an absurd notion. Yet, outside of Yerevan, provincial museums with equally important holdings have to do with even less. A phone call with the staff at the Dilijan Lore Museum and Art Gallery revealed that there are no professionals of any kind available in the region, who could help to preserve what is essentially the most significant state-owned collection of fine and folk art outside of Yerevan.

The absence of institutionalized education and qualifications was also an issue raised by the Matenadaran’s restorers who explained how their department came to be. Most of the staff have been working in the department for over twenty years. They noted that many of the newcomers come and go, most of them leaving after their probation period as they refuse to work for the minuscule salaries on offer. Nevertheless, the department head of two decades, Gayane Eliazyan, stated that those wishing to do restoration work in Matenadaran are welcome to apply. Potential candidates would be trained on-site by seasoned experts, who generously share their invaluable knowledge and skills accumulated over the years of hard work. However, almost all the interviewed specialists agreed that the profession could only flourish and prosper with the existence of proper educational facilities dedicated to the field.

In terms of education, the ROCHEMP Center is one of the few establishments that carry out small training programs devoted to conservation work. The Center was initiated by the University of Bologna and Armenia’s Ministry of Education, Science, Culture and Sport, with the support of AICS – Italian Agency for Development Cooperation. The project is aimed at vocalizing the needs of and filling the communication gaps between cultural establishments, educational institutions and the wider public in Armenia by providing short-term training courses, carrying out research and preparing educational programs to pitch to educational institutions related to management and conservation of cultural heritage in Armenia.

However, a single course unit on restoration work is far from sufficient for training a professional restorer. Aspiring restorers can only rely upon their own initiatives to get proper qualifications overseas – that is, if they are serious about their specialty and don’t view it as a “side-line” skill. But having undergone such training, which generally entails an MA in museum conservation and at least two years of entry-level work experience in a museum or private restoration lab, few are likely to return to work in Armenian institutions, where a skilled restorer is positioned on the lower pay scale than a security officer.

Restorers speak of the difficult working conditions they face in Armenia. Regardless of how weighty, time-consuming or significant the project is, the restorer’s salary remains the same and often requires them to fulfill a monthly “quota” that results in unpaid after-hours work. Most specialists stated that their motivation is obviously not financial, but rather the love and passion for art and the practice of restoration itself. However, the lack of proper financial support indicates that their efforts are entirely ignored, considering the fact that the government’s set salary for the gallery security and even the cleaning services is considerably higher than that of the specialized staff, such as restorers.

The potential dangers of this situation are self-evident. Burdened with the conservation of our collective cultural, historical and artistic heritage, restorers constantly face incredibly challenging and complex tasks, which require extreme physical and mental investment. Inevitably, the quality of the work will suffer, especially considering the fact that other than Matenadaran, most of the other institutions are not given sufficient funds for purchasing the best restoration materials or modern equipment.

This saddening picture, however, pales in comparison with the shocking situation in the regional museums, such as the Vanadzor Museum of Fine Arts.

Out of Sight, Out of Mind

Inquiries into the state of restoration work in Armenia’s regional galleries and museums revealed much more alarming conditions. The Vanadzor Museum of Fine Arts in Lori Province was founded in 1974 as a branch of NGA, but soon became an independent regional museum that encompasses more than 1700 paintings, sculptures, works on paper and ceramics. Despite the wide range of objects owned by the museum, it has only one restorer, Arpine Hovhannisyan, who has held the position since 2006 and is only specialized in the restoration of oil paintings.

Hovhanissyan says her specialization is a result of self-education—her university degree is actually in physics and informatics—but her academic background has been useful in her restoration work, as the profession requires a level of understanding in physics and chemistry. She says that she has only basic knowledge of other mediums and usually conducts minor restorations herself, only if these objects (works on paper, sculptures) are not too damaged. In case of more serious damage, the works are simply stored away from view indefinitely, as the museum does not have the financial means to engage external specialists.

Hovhannisyan agreed that most art restorers in Armenia, herself included, have insufficient training, however, the problem lies in the system itself where there is no access to training and “experts” are forced to rely upon each other’s experience and learn from mistakes. The other glaring problem is the handicap that most regional museums are facing. Hovhannisyan explained that since the NGA belongs to the central government, the restorers there have the opportunity for some short-term, quality training at the Grabar Art Conservation Center, while restorers like herself who work in the regions don’t have the same opportunity because their institutions are funded by local municipalities who simply don’t have the funds. Despite her efforts to ameliorate her skills through self-education, Hovhannisyan realizes that this is not sufficient and has been attempting for years to get the government to enable her training abroad, but without any results.

Hovhannisyan says that aside from the financial and technical challenges there is a general ignorance when it comes to understanding the intricacies of the profession. Many state officials she has met with throughout her career also don’t seem to understand the importance of a restorer’s work. This indifference to the actual actors that are meant to safeguard our heritage stands as an ironic riposte to our collective claims about the focal role of heritage preservation for the perpetuation of our national collective identity today.

Prevention as Conservation

Because natural materials are preferred over chemical ones in restoration work, they can cost a great deal of money due to the difficulty of their production. One such example is the glue used in the restoration of fragile manuscripts. This particular organic glue is produced from the bladder of the asetrina fish and is very costly. Outside of the Matenadaran, restorers in Armenia have to make do with other means.

One of the most experienced restorers at the National Gallery, Amalya Hovsepyan, who has worked at the Gallery since 1997 as a specialist of works on paper, pointed to a glass jar of handmade glue sitting on her desk that the restorers at the department made themselves from cornstarch. She explained that the Gallery lacks the finances to provide the best materials for restoration, that is why the restoration team has to be innovative in performing their tasks.

Hovsepyan also pointed out yet another issue that restorers have to face – the unsatisfactory storage and display conditions that significantly contribute to the deterioration of artworks. While temperature and humidity control systems have just recently been installed in the National Gallery’s halls, the storage facilities – where most of the Gallery’s collection is kept – still lack the proper environmental controls necessary for storing extremely fragile paintings, works on paper, photographs and other objects that require absolutely stable climate conditions throughout the year. “Oil paintings are more durable and during restoration, it is much easier to work with them than with graphite drawings, as you can easily wipe off your mistakes on oil paintings, whilst a single mistake on a pencil drawing can cause the loss of the artifact,” explained Hovsepyan. “That is why graphite gets the most damage in the archives, as it is more fragile and responds actively to chemical materials during restoration.”

In fact, few people realize that absolutely everything – from humidity and dust to the type of cardboard box used for storing artworks, or the length of display under natural light – will have an adverse and irreversible impact on most artworks. Strangely, these simple facts are often ignored or “tolerated” by the museum custodians themselves, many of whom have relatively little or no training in object handling and display rules. Even a superficial glance at the storage conditions and materials in Armenian museums would reveal a shocking lack of basic preventative approaches, such as acid-free paper and cardboard boxes, proper hanging mechanisms for paintings, or metal draws for large flat items like posters and maps. A lot of damage incurred by the objects held in the archives and museum storage facilities over the years, could have been prevented by providing the bare minimum of storage conditions and following general handling guidelines.

To be fair, none of the museums in the country have either the sufficient space for proper storage or the necessary funds to purchase essential materials like corrugated acid-free boxes. An average-sized, museum-quality archival box holding around 20 works on paper, or a single piece of textile can cost between $50 to $300 US. To rehouse its collection of over 12,000 works on paper in such a way, the National Gallery would have to spend hundreds of thousand dollars just on boxes, mounts and interleaving paper, and construct a whole new facility to properly house this collection. Needless to say, there are no such prospects for a state museum that isn’t even allocated a minimal annual acquisition fund by the State.

While it would seem that such proper storage conditions are an “indecent” luxury in the Armenian context, the fact is that improper museum upkeep becomes a much greater financial burden upon state and public funds down the road. Even worse, objects and entire collections could be lost completely when improperly stored, causing grave damage to our patrimonial legacy. Such was the sad fate of the so-called State Exhibition Fund, an enormous collection of contemporary paintings, sculptures, drawings and decorative objects acquired by the Soviet-Armenian state for travelling exhibitions. This unit was shut down, partially looted and its collection thrown into a damp basement of a high-rise apartment building like useless junk. While the remnants of this historically significant collection have recently been transferred to the National Gallery, a considerable part of it has been impaired beyond any possibility of rescue. Alas, this tragic story is not unique as many collections outside of the country’s major museums are kept in scandalously inadequate facilities that lack heating, ventilation or even proper shelving.

Restorers such as Arpine Hovhannisyan from Vanadzor have to face this reality on a day-to-day basis and wage insurmountable battles just to perform their professional responsibilities. Hovhannisyan uses a corner of the conference room in the Vanadzor Museum as her restoration station, where she sets a single tray of tools and a humble easel to carry out her part in the heavy mission of preserving Armenia’s cultural heritage. In this “DIY lab” with no equipment, the restorer is forced to rely on her bare eye-sight, intuition and subjective assumptions when doing the pre-restoration analysis and evaluation of the work. It is in such instances that pathos-filled pontifications about national heritage turn into hot air when faced with the uncomfortable truths of our on-going failure to adequately safeguard and look after the vestiges of our material culture.

Looking for a Way Forward

What is to be done then one may ask? The cost of furnishing all of Armenia’s many museums with conservation labs, trained restorers and modern amenities would be prohibitive even for economically stable states, let alone for a war-stricken country like ours. Yet, material means are not the essence of the problem here. The Gordian knot of heritage preservation would begin to be more workable with a centrally-controlled management mechanism, government-applied policies and criterias, as well as strict demands on staff qualification and training. Our material heritage would fare insurmountably better if its custodians underwent a compulsory training course on museum object care – a relatively low-cost endeavour that would have a transformative impact on Armenia’s museums. In the same vein, a centralized and state-managed restoration laboratory with a team of professionals specialized in different fields, could be created to serve all public institutions in the country, instead of focusing solely on the main museums in Yerevan.

Finally, restoration and museum management must be taken as vital and serious professions in a country that relies so much on its cultural heritage as a resource for foreign diplomacy, economy and nation-building in general. And that seriousness should be reflected in the way restorers and museum custodians are remunerated and acknowledged for their highly responsible work – work that has acquired an almost militaristic dimension in a country fighting a pernicious onslaught on its people and patrimony.

In the Armenian reality where the threat of erasure to national identity and cultural heritage is ever-present, art restoration goes beyond mere conservation to rescue the embedded historical narratives in fragile objects that tell stories of survival, resistance, and a journey of continuous healing. And as such, we as people of many fractures and wounds, deeply relate to those broken and crumpled objects that heal in the hands of professionals who selflessly carry out a widely unrecognized and unappreciated job.