Armenia’s security context marginally diminished this month, as Azerbaijan amplified its rhetorical aggression towards Armenia and engaged in expansive troop movements and build-up in the border areas, thus initiating elements of latent brinkmanship to deteriorate the security environment. This was supplemented by transferring localized operations to the domain of Nagorno-Karabakh, as Azerbaijan initiated two large operations: the sabotage of three police officers in Artsakh and the violation of the line of contact through its absorption of the strategic Stepanakert-Lisagor road. Frustrated by Armenia’s successful diplomatization of its security, Baku made extensive attempts to attack the EU for contributing to the stabilization efforts, thus joining Russia in critiquing the Western presence. As Western diplomatic pressure, along with the EU’s physical presence on Armenia’s borders, have hamstrung Baku’s capacity of amplifying its hybrid warfare objectives, this has curtailed the Aliyev regime’s ability to enhance its coercive diplomacy stratagem. Baku’s growing inefficacy to impose its will upon the negotiation process, as well as the collapse of two decades of caviar diplomacy, have produced a potentially volatile and high-risk configuration: either Aliyev will gamble and attack Armenia to compel Yerevan to acquiesce, while willing to absorb the international fallout, or continue with low-intensity hybrid operations and exhaust the peace process, utilizing the stagnation as a pretext to justify a large-scale militarized operation. Both options remain conducive to Baku’s and Russia’s interests, for in the case of the former, equitous peace with Armenia does not serve its strategic interests, while in the case of the latter, collapsing the Western negotiation efforts and controlling the conflict amounts to controlling geopolitical developments.

In this context, the region’s security arrangement remains in flux: deeper the Western involvement, deeper the rift between Azerbaijan and Europe; deeper the West’s support for Armenia’s security, deeper the alliance between Azerbaijan and Russia. As the West, especially the United States, acknowledges that Armenia’s burgeoning democracy is inherently tied to its security, the collective democratization of Armenia’s security is becoming the growing narrative. This, in itself, does not mean that the West will take Armenia’s side in the negotiations, but rather, will support an equitous peace package while curtailing Baku’s objective of subjugating Yerevan through force.

Baku’s Stratagem of Deteriorating the Security Environment

Azerbaijan proceeded to deteriorate the security environment this month by undertaking four diverse modes of activities: establishing the pretext for militarized action by falsely claiming the transportation of arms into Nagorno-Karabakh; reifying its hybrid operations by sabotaging Artsakh police officers and killing an Armenian soldier on the Nakhijevan border; intensifying its maximalist position on the forced integration of Artsakh Armenians; and amplifying its disinformation campaign. The collective endeavor of these operations appear to be designed to compensate for the limitations in Baku’s coercive diplomacy toolkit, as Western diplomatic pressure and the EU’s presence on the border have undercut Azerbaijan’s ability to undertake cross-border incursions. In this context, whereas continuous incursions into Armenia-proper had become Baku’s post-war modus operandi in implementing its coercive diplomacy stratagem, this strategy found itself constrained after the enhancement of direct Western involvement. To compensate for this limitation, Baku has shifted its domain of hybrid activities to Nagorno-Karabakh. While this inherently diminishes Baku’s capacity to coerce Yerevan, it does, however, create a severe obstacle to the peace process that Yerevan cannot ignore. To this end, Azerbaijan’s activities are not so much designed around securing concessions from Stepanakert, but rather, derailing the negotiation process.

By methodically engaging in salami slicing and strangulating Artsakh’s ability to function as a statelet, Baku is hoping to create new facts on the ground, one that it will use to deny any role for the rights of the Artsakh people in the negotiation process. It is one thing for Baku to argue that the Nagorno-Karabakh issue does not exist, but it’s another thing to face the reality on the ground and concede that it does not have control over this territory. Thus, by slowly establishing control through blockades and methods of borderization, Baku seeks to align its rhetoric with the new facts that it creates on the ground. Knowing full well that Yerevan cannot agree to any peace proposal that negates the minimum security of the Artsakh Armenians, Baku is seeking to restructure the nature of the negotiations: either Armenia forgets about the Artsakh population, or there is nothing to negotiate.

The probability of implementing such a strategy after the November 9, 2020, ceasefire agreement would have been almost nonexistent, since the Russian presence was qualified as a robust deterrent against such a probability. But as the last two years have demonstrated, Russian peacekeepers function more like an impotent observation mission than an armed contingent mandated with keeping the peace. Recognizing that Russia has almost no deterrent effect upon its continuous hybrid operations, Baku has reconfigured its strategy: the strangulation and borderization of Artsakh. Thus, as Russia abdicates its responsibilities under the trilateral agreement and stands by as Baku implements its strangulation stratagem, the facts on the ground continue to be incrementally changed: from the Parukh assault, to the Lachin blockade, to sabotage operations, to the borderization of the Stepanakert-Lisagor road.

The West’s Stabilization Effort

As Russia’s continuous willful negligence contributes to the deterioration of the security environment, the West has stepped in to establish manageable stability. With the fusion of intense U.S. diplomatic pressure, as well as the direct involvement of Secretary Blinken, along with the EU Civilian Mission on the ground, the West is seeking to stabilize the situation before Azerbaijan transitions from low-intensity hybrid operations to high-intensity incursions. Baku’s frustration with such developments has been fully complemented by Russia, as both sides have aligned in their aggressive attacks against the West. More so, Moscow rejected PM Pashinyan’s claim that under the trilateral agreement, Russia served as “guarantor of the security of Nagorno-Karabakh,” with Russia’s MFA directly stating that Russia does not see itself assuming such a responsibility. Thus, with Russia’s concession of its abdication of responsibility, and its continued deepening of relations with Azerbaijan, the Western presence has become fundamental to curbing Azerbaijan’s behavior.

Interestingly so, the Russo-Azerbaijani posturing against the West suggests well-developed coordination. Russia declared “that the goals pursued by the U.S. and the EU are aimed not at achieving peace and security in the South Caucasus, but at wedging into the peace process” and seeking to play a “destructive role,” while Azerbaijan, similarly, argued that the EU mission is “not a civilian mission” and accused it of undermining the “normalization process” by engaging in “false and slanderous allegations.” The observable synergy in the anti-Western narrative disseminated by both states was also remarkably consistent in their critique of having a United Nations presence in the region. Azerbaijan directly stated that the presence of a “UN fact-finding mission to Karabakh, to the Lachin road” is completely unacceptable, while Russia simply mocked the idea of having a UN mission on the ground.

As Russia and Azerbaijan have established a united front against a Western presence in the region, Armenia has proceeded to reconfigure its strategic interests. In this context, it has advanced its democracy narrative, while aligning its preferences to the resolution of the conflict with the Western-led stabilization efforts. This was most evident in PM Pashinyan’s visit to Germany, where he noted that the EU “mission will play a significant role in establishing peace and security in the region,” and that the basis of Armenia’s “cooperation with Europe is democracy,” and as such, “democracy is a strategy” for Armenia, one where democracy can hopefully be “able to provide security.” Pashinyan further expanded on this new doctrine of democratizing Armenia’s security, stating that Armenia does not have domestic threats to its democracy, but rather it has “external threats to our democracy,” qualifying Azerbaijan’s objectives as one of trying “to destroy all the democratic achievements of the Republic of Armenia.” By geopoliticizing Armenia’s fight for democracy, Pashinyan drew a clear link that is shaping the growing Western narrative: “Azerbaijan’s continuous escalations, aggressive rhetoric, and hate speech are a great threat to Armenian democracy.”

Armenia’s geopoliticization of democracy has not gone unnoticed by Azerbaijan, as Baku expressed its displeasure by declaring that “Armenia cannot secure its future with calls to world leaders, claims for the role of stronghold of democracy and various resolutions.” Yet this is precisely how the Western-led stabilization efforts have proceeded: utilizing diplomatic pressure to cocoon Armenia’s security, thus supporting the survival of Armenia’s democracy. This has been most evident in America’s robust support for the EU mission on Armenia’s borders, thus aligning the collective Western position on the stabilization efforts. Canada has also immersed itself in this effort, joining a chorus of Western states condemning Azerbaijan’s behavior and demonstrating support for democratic Armenia. The European Union unequivocally voiced the same posture, with the European Parliament not only condemning “Azerbaijani military actions,” but also noting that “EU-Armenia relations are based on common values such as democracy, the rule of law, human rights and fundamental freedoms,” and that Armenia is “a leader in democracy in the region.” In this context, a collective trend is crystallizing within the broader Western narrative, and this was more clearly reified by Armenia’s invitation this month to the White House’s Summit for Democracy.

EVN Security Report

Examining the Context

Resilience

The Growing Russo-Azerbaijani Axis and Why Armenia Must Adopt a Porcupine Doctrine

Ontological Security and Azerbaijan’s Aversion to Peace

Deterrence by Denial and Azerbaijan’s Aggressive Opportunism

Hybrid Warfare and the Asymmetrical Disparity

Diplomatization of Security

The Problem of Illiberal Peace

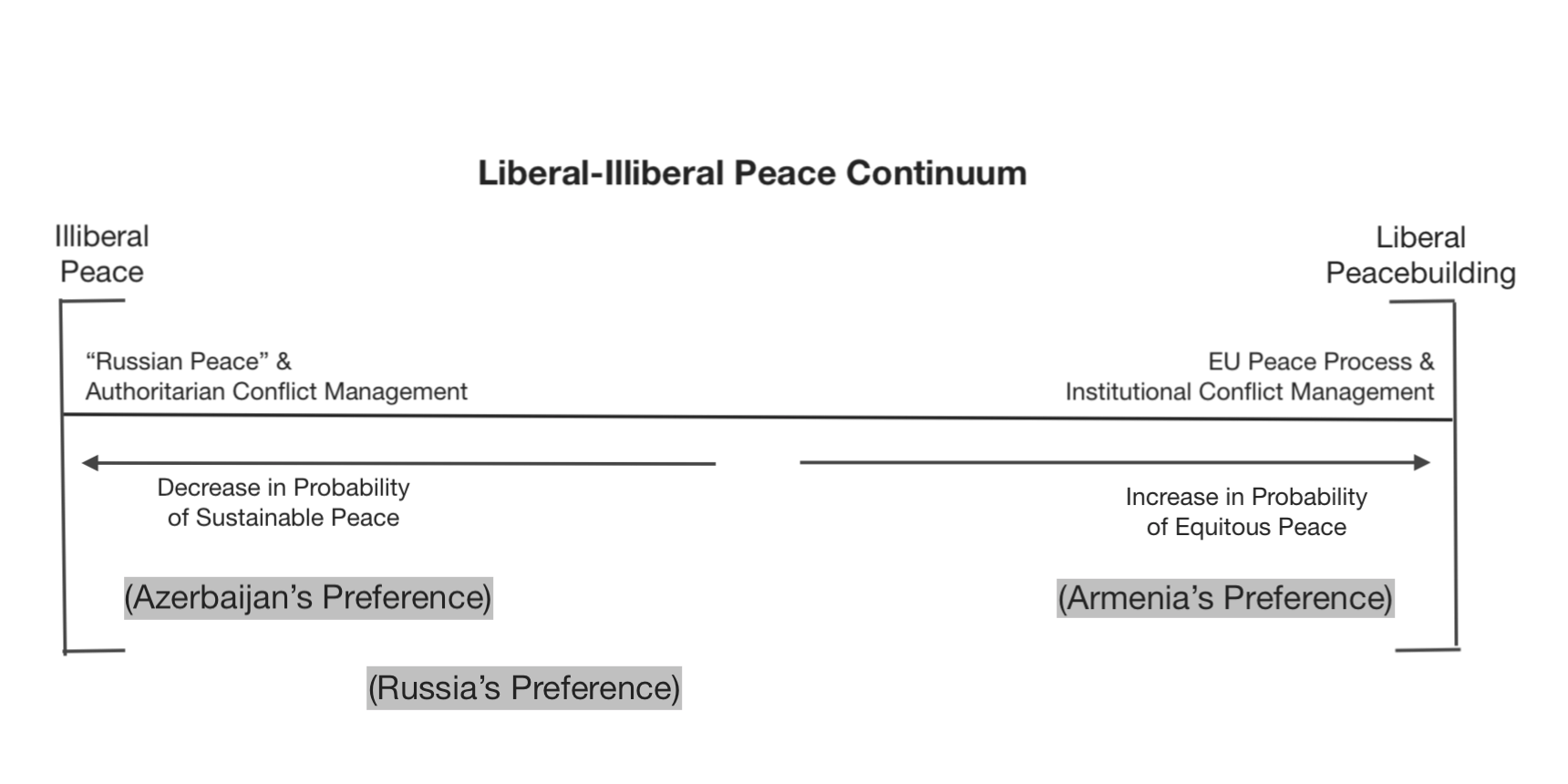

The West’s stabilization efforts, Azerbaijan’s obstructionism, and Russia’s endeavor of monopolizing the negotiations process have created a three-tiered structural problem for Armenia. First, while the West’s stabilization efforts are fundamental to Armenia’s nascent security architecture, Armenia nonetheless understands that there can be no peace process without some consideration of Russian interests. Second, the formation of a Russo-Azerbaijani axis is precisely designed to either derail the negotiation process, or prolong it into an untenable status quo. And third, a Russia-mediated peace process cannot produce equitious peace, but rather, provide the framework for the continuation of a frozen conflict. In essence, what Russia and Azerbaijan aspire to is some configuration of what the literature on peace and conflict studies calls “illiberal peace.”

Conceptually, liberal peacebuilding is defined by inclusivity, equity, institutionalized mechanisms, arbitrations, absence of coercion, and other instruments of nonviolent problem-solving. Illiberal peacebuilding, on the other hand, is defined by coercion, militarized outcomes, arbitrary stipulations, kinetic diplomacy, and normalization of violence.

For Azerbaijan, an illiberal peace allows for the continuity of low-intensity hybrid warfare and conflict-persistence, thus feeding the domestic needs of the Aliyev regime. For Russia, an illiberal peace allows Moscow to have both leverage and a controlling stake in the process, where the peace process is not about the two parties achieving equitious peace, but rather, one where Russia’s interests supersede the interests of the warring parties. As a large body of scholarship demonstrates, authoritarian conflict management, while the preferred outcome for countries like Russia, is not conducive to sustainable peace, and as such, Russian-led negotiations cannot produce equitious and peaceful outcomes. On the other hand, multi-national or supranational negotiations and conflict management processes do, in fact, exponentially increase the probability of attaining sustainable peace. Extant sets of case studies demonstrate the attainment of “quality peace” nurtured by the European Union, or the fusion of EU, UN, and other international organizations. Examples include complex conflicts that were resolved through liberal peacebuilding: Sierra Leone, Liberia, East Timor, Bosnia and Kosovo. In this context, to alleviate the three structural problems facing the current peace process, it is in Armenia’s strategic and long-term interest to proceed with the liberal peacebuilding track established by the European Union, as opposed to the illiberal peacebuilding platform offered by Russia. The rationale for this preference is purely empirical: liberal peacebuilding is not in Russia’s toolkit, while an illiberal peace would be detrimental to Armenia’s future security. Further, and among other things, as the last two years have demonstrated, conflict management, peacekeeping, and peace negotiation models utilized by Russia have not only failed to establish any progress towards peace, but to the contrary, have degraded Armenia’s security environment. To escape the trappings of illiberal peace, Armenia must avoid the negotiation platform designed by Russia, which not only prolongs the process, thus serving the interests of Azerbaijan, but also heightens Armenia’s state of insecurity, potentially forcing Armenia to fall back into an unhealthy dependency upon Russia.

Anna Ohanyan’s scholarship on the subject demonstrates that approaches to liberal peacebuilding, with emphasis on equity and protection of minority rights, is juxtaposed with the illiberal process dominated by states with “domestic authoritarianism and militarized foreign policies.” In qualifying the pertinent case studies on “Russian peace,” Ohanyan notes that Abkhazia, South Ossetia and Nagorno-Karabakh have been positioned within a “fragile and uneasy stability.” In the specific case of Nagorno-Karabakh, “Russian peace,” in the face of Baku’s continuous bellicosity, has been “increasingly ineffective in moving fragile peace processes forward.” The horizontal scale upon which the peace negotiations are found, from Russian-led illiberal peace on one hand and EU-led liberal peacebuilding on the other, is the continuum that Armenia must strategically navigate.

Whereas liberal peacebuilding concentrates on the establishment of constructive and mutually reinforcing mechanisms to enhance the negotiation process, illiberal peacebuilding encourages coercive and kinetic diplomacy, with intermittent utilization of hybrid warfare tactics. As such, since November 2020, instead of the Russian-led peace process contributing to relative stability and calm, the results have been precisely the opposite: incursions into Armenia proper, interstate militarized operations, and increased strangulation of Nagorno-Karabakh. Thus, whereas liberal peacebuilding restrains coercive and kinetic diplomacy, illiberal peacebuilding remains acutely conducive to it. As such, the Russian-led model has contributed to both the deterioration of Armenia’s security environment as well as the intensification of Azerbaijan’s bellicosity. It is precisely within this configuration that the EU-led liberal peacebuilding model becomes crucial for Armenia: it stabilized the deterioration of Armenia’s security environment, while restraining Baku from amplifying kinetic diplomacy.

The push and pull of the diverging forces within the continuum will determine both the trajectory of negotiations, as well as the scope and extent of Azerbaijan’s bellicose demeanor. If the negotiation process proceeds with the illiberal peace model, Baku will continue to intensify its hybrid warfare and kinetic diplomacy stratagem, with Russia displaying implicit indifference to Armenia’s suffering. On the other hand, if the negotiations develop and strengthen through the liberal peacebuilding model, not only will Azerbaijan’s belligerence be contained, but the structural mechanisms informing the peacebuilding process will contribute to Armenia’s security situation. To this end, one negotiation track leaves Armenia vulnerable to aggression and subjected to authoritarian conflict management, while the other track relatively reduces the security threat while enhancing the probability of equitous peace. In more simple terms, illiberal peace is designed to secure a victor’s peace, the end game for the Aliyev regime, while a liberal peace is designed for a just peace, the end game for any democracy.

I have read your articles over the past several months where you describe the evolution and movement of Armenia’s diplomacy away from Russia and towards the West. You have spoken approvingly of the EU mission and the US involvement in halting the Azeri invasion of Armenia in September 2022. This month you highlight the importance of Armenia‘s march towards democracy. But what I find very concerning is that France, the EU and US have provided no military hardware to support this fledgling democracy. I don’t see C-130 aircraft landing in Yerevan. Whenever there is an encroachment of Armenia’s and Artsakh’s borders by Azerbaijan, there is no retreat. I am wondering whether the soft power that Armenia has developed is enough to deter Azerbaijan. So far it has not. I am also reminded of the fact that Armenia is totally dependent on Russian gas for energy, its only route north is through the Lars Pass in Georgia, its nuclear power station is run by Russian fuel, and most large infrastructures in Armenia are owned by Russians. Is it possible that Armenia (and Georgia) misread Russia’s intentions vis a vis Azerbaijan and Turkey? Historically Russia wanted to have a Pax Russica in the South Caucasus; as long as Russia had the final say and its interests were secure, it was not anti Armenia, anti Azerbaijan nor anti Georgia. In fact it was in Russia’s interest for the three republics to cooperate. Is it possible that Armenia could have a made a deal on Karabagh blessed by Russia ( for example sharing Shushi , giving back Agdam but keeping Lachin and Kelbajar to secure its eastern front) ? That deal could have spared Armenia lots of anguish. When Armenia went against Russian advice, it used Azerbaijan to punish Armenia and continues to do so today. The situation in Georgia is not dissimilar to Armenia; lots of promises from EU but not much help to become truly independent of Russia. As the Belarus president Lukashenko said, “Armenia has nowhere to go”. It seems to me that either a) The West steps up its aid significantly to Armenia along the Ukrainian model b) Iran/India invest massively in Armenia c) Armenia and Diaspora get really serious about nation building ( i.e increase its investment by billions of dollars to revitalize economy and reverse demographic trends) or d) Armenia goes back to Mother Russia.