The Armenian Genocide left thousands of children orphaned and homeless. Traumatized by the horrific events, tortured and starving, most of them found refuge and a home in the hundreds of orphanages that were created to house them and meet their physical and spiritual needs in numerous countries in the region, including in the Middle East.

We often hear about the Genocide orphans, but we seldom speak about their lives and destinies. How did they end up at the orphanage? How was their experience there? Later in life, many of them never spoke about the years spent in an orphanage. The trauma never allowed them to say things out loud. But those who spoke left behind stories of an entire generation…

Hayastan Sargsyan: Story of Separation

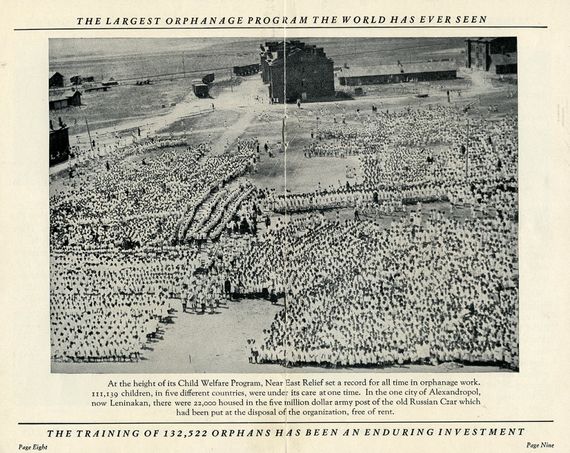

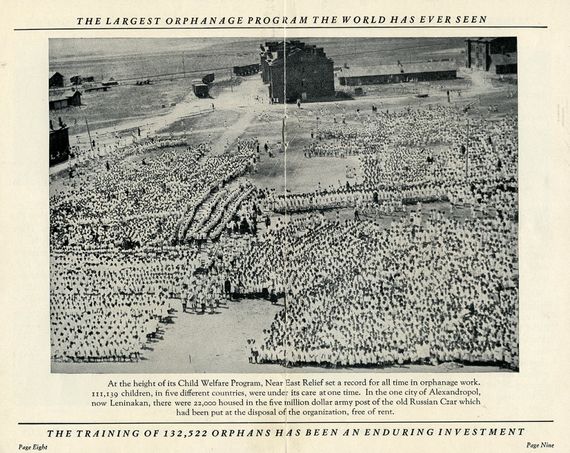

Gayane Aslanyan, 45, recalls her grandmother Hayastan Sargsyan’s story of survival and orphanage life. “My grandmother was born in 1914, in the village of Armutlu of Basen region, Western Armenia. Her parents were murdered by the Turks, and she and her newborn brother Nerses were left in the care of their grandfather Hakob. After hiding the remaining members of his family, Gevorg was able to secretly flee to Alexandrapol (present-day Gyumri) in 1915 with his grandchildren. There, he decided to leave Hayastan and baby Nerses at the American orphanage of Gyumri founded by the Near East Relief.* From that day on, Hayastan and Nerses had only each other. However, in 1919, the Americans took Nerses to the United States and Hayastan never saw him again. A year later, the Americans came back to take her as well, but Armenia was already a part of the Soviet Union and the authorities did not allow them to take the children.”

Till the very end of her life, Hayastan Sargsyan never stopped thinking about her baby brother. “She would cry every time she spoke about Nerses,” Gayane recalls. The family tried to find him through relatives living in the U.S., although they did not continue because some of their relatives in Soviet Armenia were working at the KGB and requests to the U.S. were forbidden.

Hayastan Sargsyan lived in the American orphanage for several years. While there, she lied about her age to be able to work at a jam factory. “She was quite young and would pull up a chair to have enough height to mix the jam in the cauldrons,” Gayane recalls. “It was probably because of that job that she was an outstanding cook.” Although Hayastan did not share many stories from that period of her life, she would recall that the Americans were very caring and supportive towards the orphans. After spending several years at the orphanage, Hayastan was taken to her uncle’s house and lived there until her marriage. “Her uncle was working at the orphanage, and he had managed to find Hayastan,” Gayane says.

The trauma of separation and loss had left a scar in Hayastan’s soul. “My grandmother had an interesting behavior,” Gayane recalls. “Every time she would not find one of her belongings, for example, her soap or her socks, she would think that it was stolen. From a very young age, everything was taken away from her, her parents, brother…”

Hayastan Sargsyan lived until the age of 84, had a loving family and five sons. Her younger son was named after her lost brother. She passed her dream of finding Nerses on to Gayane, her granddaughter, who continues the search, sparing no effort to discover what happened to Nerses and maybe find his offsprings somewhere in the U.S.

Satenik Ghazaryan: Story of Reunion

Susanna Mkrtchyan, a painter, an “Honorary Worker of Culture” and head of the Gyumri branch of the Henrik Igityan National Center of Aesthetics is the child of two genocide survivors. Her parents came from Western Armenia and lived in the orphanages of Gyumri. “My mother, Satenik Ghazaryan was born in Surmaly, Western Armenia in 1910 and had four sisters and a brother,” she recalls. “When the massive massacres began, my mother’s family managed to escape and reached Karakilisa (present-day Vanadzor). Her brother died on the road, and several days after reaching Karakilisa my grandparents died from malaria. My mother and her four sisters were orphaned, and their surviving grandfather decided to send the three youngest girls to the Gyumri orphanage and kept the older two with him.”

Satenik Ghazaryan and her two sisters were first taken to Polygon orphanage of Gyumri. “According to my mother, the building didn’t have windows or proper doors and the orphans had to tightly hug each other in order not to freeze at night,” Susanna says. “And each morning several children were found dead because of the cold.”

Soon, Satenik was separated from her sisters and was sent to the American orphanage of Stepanavan. “Americans were preparing young girls to be future housekeepers,” Susanna notes. “They were very kind to them, they would educate them, teach cooking, embroidery, and several languages. My mother was in the last group of girls that was supposed to travel to the U.S., but Alexandr Myansikyan, Chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars of Armenia at the time, did not allow that.”

Susanna says that her mother received her education thanks to the American orphanage. “I remember her singing for us in English; that was considered something special during the years of Soviet Armenia.”

After spending some time at the American orphanage in Stepanavan, Satenik Ghazaryan was lucky enough to be reunited with her younger sisters. The story of the sisters’ reunion was unexpected and very emotional and left an indelible mark on Susanna’s memory.

“One day, my mother, and other girls from the orphanage, well-dressed, hairs beautifully tressed, dolls in their hands, were taken to Gyumri’s Polygon orphanage to interact with the other children. The orphans there were barefoot, bald and unwashed. They were playing near a small pond. Suddenly, my mother sees a young girl with a birthmark on her face and immediately remembers her younger sister. She approaches her and asks:

‘What is your name?’

‘Heriqnaz,’ she answers,

‘Do you have sisters, parents?’

‘My parents are dead, but I have sisters – Satenik and Nazeni.’

“Excited by the reunion, Satenik wants to hug and kiss her sister, but her American teacher forcibly separates them saying that the orphans are infectious, and she will get sick if she touches her sister. “My mother always remembered that she was on a buggy and her sister standing in front of her and they were not allowed to touch each other. Seeing that there was no way to reach each other, Satenik threw her doll to Heriqnaz.”

The sisters eventually reunite.

Satenik Ghazaryan lived a beautiful life, married a man from her hometown and had seven children. As her daughter recalls, she was a beloved person who loved to take care of all the people around her. “When my mother died, a person walked up to her coffin and started to cry,” says Susanna. “We did not know who he was, and later on it turned out that he was a poor orphan and my mother had taken care of him for some time.”

Maro Alazan: Story of Famine

Maro Alazan, wife of 20th century Soviet Armenian writer Vahram Alazan, faced crippling hardships throughout her life starting with the atrocities committed against the Armenians by the Ottomans, to Stalin’s repressions and eventual exile in Siberia. She was an orphan from Western Armenia, who was given a second chance at life at an orphanage in Etchmiadzin. Maro would write about the terrifying memories of her tragic life in a two-volume diary. “This is not only my tragedy; this is my nation’s tragedy,” she wrote on the first page of her diary.*

Maro was born in 1908 in Western Armenia and lost her entire family as they were escaping the massacres. She was saved by a Russian soldier who took her to the orphanage. The Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin had become an open-air residence for hundreds of immigrants and orphans. Maro would never forget the half-naked, dirty and hungry children. “The classes at Etchmiadzin Seminary were canceled and the building was serving as an orphanage,” writes Maro in her diary. An orphaned child who had absolutely nothing was thrilled to finally find a home and interact with children of her age.

Alas, her happiness did not last long. Because of the horrific conditions and chaos in the city, including lack of food and medicine, Etchmiadzin had been transformed into a city of cholera and famine. “At night, 32 children went to sleep and only 18 woke up in the morning,” Maro writes. “Fourteen of them said goodbye to us and sank into an everlasting sleep.” In the days that followed, Maro and the other children were examined by doctors and sent to another orphanage in Nakhijevan, where they were properly taken care of. It was there that Maro finally received a pair of new shoes. “There was no limit to my happiness; I had new shoes, red shoes. Since I left our village, I did not have proper shoes. My feet were already used to any thorn and thistle.”

After spending several months at the Nakhijevan orphanage, it was time to return to Etchmiadzin. Here, more hardship was waiting for Maro and her orphaned friends. “It was 1918, a year of famine, poverty, dirt, orphans, deaths. People were dying from typhus.” Maro writes that destitute immigrants were wandering in the streets, trying to find any scrap of food in the piles of garbage. The orphans were also hungry. “Every day we would go to the fields and eat grass and come back home dreaming of fresh bread.”

But that was only the beginning of what was to be experienced…

“You could not find dogs, cats or chickens in the streets of Etchmiadzin. One day, a beautiful chubby dog appeared in the yard of our orphanage. A raw-boned man with bloodshot eyes and a bloated face attacked the dog with a big knife and cut off its head. He hungrily took the body and disappeared from our sight. Several young girls ate the dog’s coagulated blood, and we watched grudgingly as there was nothing left for us.”

The blood of a dog, and bread infested by worms. Maro would write that these were the most desirable food for the orphans. However horrifying those experiences were, they not stop believing in a better life. Every day they would go to school, do their homework, learn embroidery, they would help to clean the orphanage and would even sing and dance.

“There was strict discipline, ideal cleanliness, and religious upbringing in our orphanage. We would sing ‘The Dawn of Light’ [Armenian sacred song ] every morning and ‘Lord have Mercy’ in the evenings, but that God would not have mercy on us, and we were always hungry.”

Several years later, Maro Alazan was taken to one of the orphanages in Yerevan. She later married poet, literary critic and head of the Writer’s Union Vahram Alazan. She led a charmed life among the intelligentsia of 1920s Yerevan. This, however, would soon by interrupted by the Stalin terrors. Maro, as the wife of a “counter-revolutionary” and “nationalist” would be arrested, tortured and exiled to Siberia.

Sime Mouradyan: Story of Sacrifice

Sime (Simezar) Mouradyan was a nurse at the American Red Cross orphanage in Etchmiadzin. Born in 1889 in the village of Aygedzor (Van), Sime grew up in a family of farmers. Her childhood memories were tied to Mount Sipan and Lake Van, where she would spend her days trying to catch tarekh* with her friends. Sime would later recall those days with longing, saying that there was no enmity between her Armenian, Kurdish and Turkish friends. However, the peace and joy of childhood soon came to an end in the aftermath of the Hamidian massacres* and Sime, together with her mother, fled Van in 1896.

In September 1896, after crossing Igdir, Sime and her mother, Gyulizar, together with a caravan of refugees got to the border of Eastern Armenia where Russian border guards welcomed them and provided them with food and water. For a few months, they lived in the courtyard of St. Gayane Church in Etchmiadzin, but once winter began, the Catholicos gave an order to turn nearby barns into shelters and settle the refugees there. When the summer heat wave arrived, Sime’s family and several other families from Van asked the Catholicos to move them to a cooler place, as “the heat of the Ararat valley was unbearable compared to Van.” In 1897, Sime moved to the village of Shirvanjugh (present-day Lernakert, Shirak Province), where in 1903 she married Hovhannes Badalyan. When their first son, Sedrak turned five in 1910, they moved back to Etchmiadzin and had two more children. Soon Hovhannes became seriously ill and passed away, leaving Sime alone with three little children.

“Sime was a very self-contained woman, emotionally affected by everything that had happened to her. She was silent most of the time, but when she was in the mood, she’d tell me about the American orphanage as I reminded her of the Americans she met there. They were always polite and kind to everyone,” says Gohar Badalyan, the wife of Sime’s grandson.

Sime started working and living in the American Red Cross orphanage of Etchmiadzin in 1915. Prior to that, she had worked in the Armenian orphanage of St. Gayane Church for a few months. However, her children weren’t allowed to stay there with her, and she had to seek ways to find permanent shelter for them. As Gohar recalls, Sime would often draw parallels between the Armenian and American orphanages, two very different realities. According to her stories, the orphans from the Armenian orphanage lived in miserable conditions, were always sick and deprived of food and proper clothes. Almost all of Etchmiadzin was full of unburied bodies. The American orphanage had sufficient food supplies as well as clothing for children and the overall environment seemed less gloomy.

“Sime always spoke kindly about the missionaries who visited them. In the winter, for the New Year’s celebrations they would bring colorfully-wrapped candies and biscuits in addition to the daily meals of the orphans. They always played with the children, cuddled and carressed their little heads.”

Sime worked at the orphanage until 1918, but the stories and images forever remained in her memory, making her feel nostalgic at times. “She’d ask me to add some milk or kakavo [meaning cocoa] into her coffee, which remained her favorite drink till the end of her life. I figured out that kakavo was the famous chocolate milk. It was a tradition she acquired from the American orphanage. Every day, they would give children a cup of chocolate milk. All the children who entered the orphanage were emaciated. Sime believed that it was thanks to that kakavo that they stopped looking pale and their cheeks became round again,” says Gohar.

The orphanage years also brought more fears and added on to her long-existing trauma. A lot of foreigners often visited the orphanage for adoption. “They didn’t adopt two or three kids, but 30 or 40 of them at a time,” Sime would tell Gohar. These children were carefully selected and taken abroad to work as housekeepers or textile factory workers. Sime’s two daughters were among those ‘chosen ones’ and would have been separated from their mother if their 12-year-old brother Sedrak together with his young uncle didn’t walk all the way to Yerevan to rescue his sisters. Then the four of them walked back all the way to Etchmiadzin.

Sime was terrified by the thought of being separated from her daughters and the fear of losing her beloved ones lingered until the very end of her life. In 1965, when she was already 75, her grandson, Mushegh, left Etchmiadzin for Yerevan to write his university entrance exams. Affected by the traumas of the past, Sime kept crying all day, saying that her grandson’s life was endangered. “She kept repeating, ‘In what sands now should I bury my head?’”

Sime passed away in 1973. Gohar recalls, “Until her very last days, she kept saying that had there not been the American nurses and missionaries, those who survived the massacres would have died from hunger and cold.”

Ghevond Elbakyan: Story of Torture

Sixty-three-year-old Susanna Elbakyan is the head of the Holy Land NGO, which is concerned with the conservation and preservation of cultural sites in Gyumri. Susanna’s paternal grandfathers were originally from the town of Terjan, Erzurum. Her father, Ghevond Elbakyan was born in 1910 and lost both of his parents at an early age. Ghevond was only eight when his mother, Araksi died after being struck by lightning. Two years later, in 1920 his father was killed by Turkish soldiers in a place called the Massacre Gorge,* 25 km north of Gyumri. “The Turks lied to them, telling that the war was over and they could continue living their normal lives, but then they forcibly took all the men to the gorge and killed them,” says Susanna, who is currently recording and preserving her father’s memoires.

After the deaths of Ghevond’s parents, his three uncles appropriated the family fortune and took Ghevond to the American orphanage along with his younger siblings, Epraksya and Shimavon. When Ghevond arrived in the orphanage, most of the orphans had pruritus including his 6-year-old sister Epraksya. “He would always hold her sick hand tightly, worried that he might lose her. But soon some of the doctors took her away and he never heard from her ever again. Everytime my dad talked about his sister, tears would roll down his face.”

After spending a few months in the orphanage, Ghevond and his brother ran away to seek shelter at his elder uncle’s place. “My father’s uncle took the shoes that were a gift by the orphanage doctors and gave them to his own son.” Disappointed by the cruel attitude of his uncle’s family, Ghevond went back to the orphanage.

“I remember that they would give us hot soup. We were sitting on the floor, eating the soup,” Ghevond used to tell Susanna. The nurses working in the orphanage were mostly from the States. “They were rather strict. Once a group of doctors arrived at the orphanage. They brought the children warm shoes and white scrubs. They examined them very carefully and cut their hair very short because of the widespread lice.”

Ghevond left the orphanage at 13, leaving his younger brother there. However, there were more hardships awaiting him in the future. Ghevond participated in World War II and ended up spending five years in Nazi concentration camps. “My dad told me terrible things from those years. People died of hunger. Things were so bad they had to eat human flesh. Men, women, children – all of them were tortured constantly,” Susanna recalls, pointing out that those hardships didn’t make her father any weaker. “After the war, my dad had ten children and he taught all of us how to be united and how to stay strong. The cruelty he saw and experienced only made him stronger.”

—————————–

*Memories are taken from Maro Alazan’s two-volume diary that is kept at Yeghishe Charents Museum of Literature and Art

**Tarekh is a fish that is indigenous to Lake Van. The Latin name is alburnus tarichi

*** Hamidian massacres: Massacres of the Armenian and Assyrian people in the Ottoman Empire throughout the mid-1890s

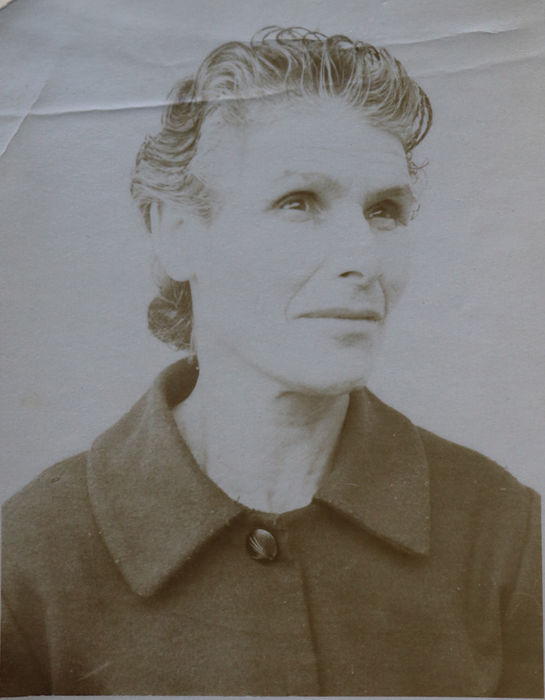

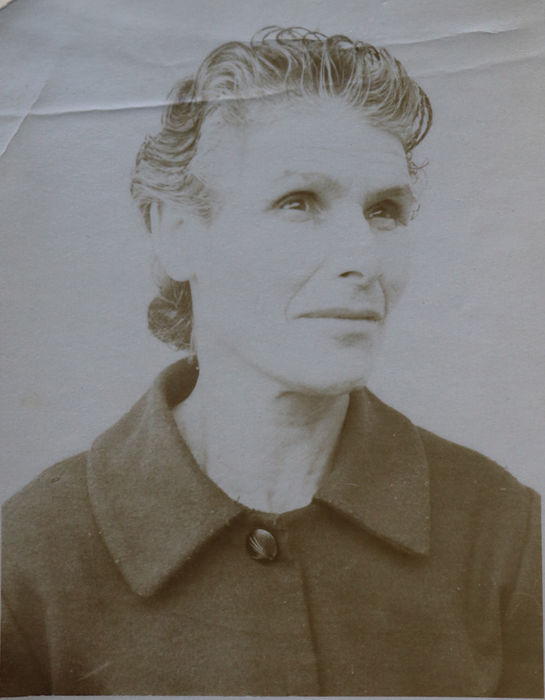

Hayastan (far right) with daughter-in-law and grandchildren.

Hayastan Sargsyan. Images courtesy of Hayastan Sargsyan’s family.

Waiting at the doors of the orphan city, Alexandrapol.

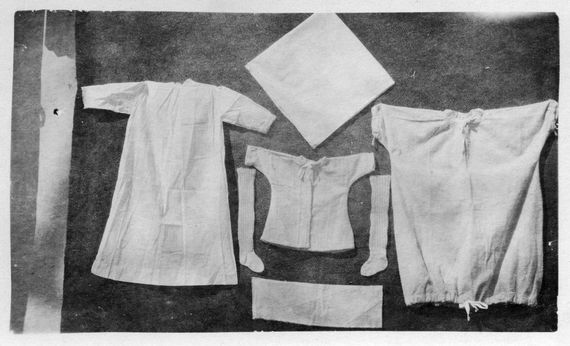

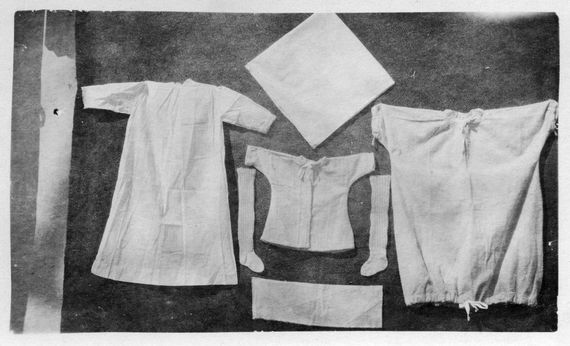

Layette for orphans.

Young children from Syra Orphanage receive dolls donated by well-wishers in the United States.

From left to right- Gurgen Mahari, his wife Ofelya, Vahram Alazan and Maro Alazan, 1933, Leninakan (currently Gyumri).

Maro Alazan in 1935.

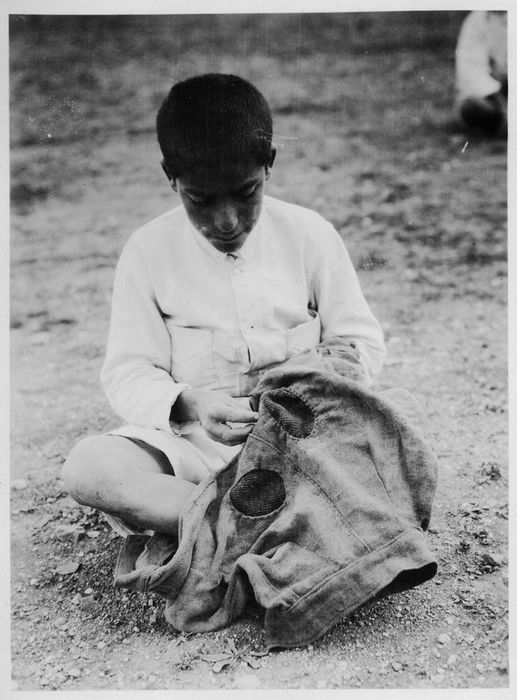

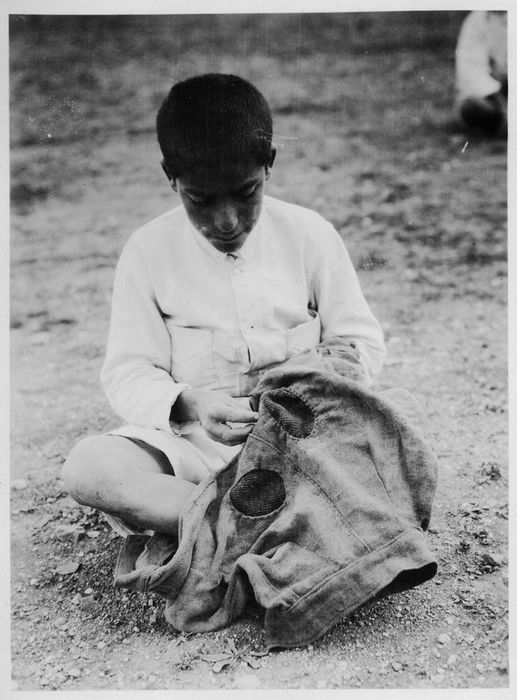

Armenian orphan girl sewing.

Orphans in rags, Armenia.

Sedrak (Sime’s son), Sime’s daughter and Sime’s brother, Karo. Image courtesy of Sime Mouradyan’s family.

Nurse and child with a rabbit at the orphanage complex at Alexandropol. The young woman may be a student or graduate of the Edith Winchester Nursing School.

Ghevond Elbakyan (right). Image courtesy of Ghevond Elbakyan’s family.

This photograph of a boy repairing a pair of trousers appeared in a Near East Relief publication with this caption: “When the clothing can no longer be patched, it is cleaned, cut up and used as filling for mattresses and pillows.”

Archival images used are from The Near East Relief Digital Museum.