Claiming the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict Has Been Resolved

Shortly after its victory in the 2020 Artsakh War, Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev began stating that there is no longer a Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. Moreover, he publicly admitted that Azerbaijan initiated the war to “resolve the conflict.” The use of force is a violation of Article 33 of the UN Charter on Peaceful Settlement of Disputes, and done with disregard to UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres’ March 2020 call for a global ceasefire in light of COVID-19.

Azerbaijan glorifies its military aggression in Nagorno-Karabakh as a means for conflict resolution, aiming to legitimize its results by refuting compromise and based on its unilateral interests. It justifies the war by the necessity to restore its territorial integrity, while having occupied not only areas surrounding Nagorno-Karabakh but having violated the integrity of Nagorno-Karabakh itself through the occupation of Shushi and Hadrut, and having conducted ethnic cleansing there. It ignores the unresolved nature of the root causes of the conflict and their deterioration since the war.

Refuting the Further Need for the OSCE Minsk Group

Azerbaijan casts the blame for not brokering a resolution to the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict on the OSCE Minsk Group, the official mediating body of the conflict. Since the 2020 ceasefire statement, Azerbaijan has blocked the role of the Minsk Group in the resolution of the conflict and has used offensive language referring to it. Armenia has been reiterating the importance of the continuing role of the OSCE Minsk Group.

The Minsk Group has offered several solutions to resolve the conflict between the first and second Nagorno-Karabakh wars. However, most of those proposals were rejected by Azerbaijan, which was evidently trying to win time while directing a large proportion of the profits gained from the exploitation of oil and gas pipelines to its army and preparing for the next war. Allegedly, Armenia was also not eager to accept most of the proposals either due to the lack of domestic consensus and because of it benefitting from the status quo.

The Minsk Group has been experiencing obvious difficulties due to polarized relations between the OSCE Minsk Group co-chair countris – Russia, U.S. and France in light of the war in Ukraine. Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov back in June of this year stated that the OSCE Minsk Group has ceased its activities because of the lack of cooperation of its American and French co-chairs. However, the role of the OSCE Minsk Group was reaffirmed in the Joint Statement between Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan and Russian President Vladimir Putin signed in April 2022. The American and French co-chairs have also reiterated their willingness to continue their role in the body and have even expressed readiness to meet the Russian co-chair. Azerbaijan’s Foreign Ministry aggressively reacted to references to the OSCE Minsk Group by the U.S. and France in August 2022.

The reason Azerbaijan refutes the role of the OSCE Minsk Group is its unwillingness to return to the appropriate framework for the resolution of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict and its principles agreed to before the 2020 Artsakh War, such as deployment of international peacekeepers to ensure the security of civilians, granting an interim status to Nagorno-Karabakh and anticipating a referendum for its final status. The reason Russia prevents the role of the group is to monopolize the mediation and facilitation of the conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan in line with its geopolitical interests in the region. However, the U.S. and France, as well as the EU, are trying to regain their diminished role during and after the 2020 Artsakh War.

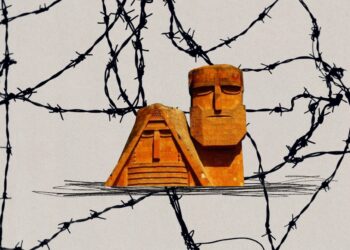

Refuting the Existence of Nagorno-Karabakh

Aliyev claims that Nagorno-Karabakh doesn’t exist as an entity and censors the use of the name by international actors. He says there is only a wider region of Karabakh, and what is now needed is the integration of the territory still controlled by the local authorities of Nagorno-Karabakh into Azerbaijan as part of this wider Karabakh region.

Even the Soviet authorities could not ignore the fact that Armenians constituted a predominant majority of the population of the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Region (89.1% Armenians and 12.59% Azerbaijanis in 1926; and 75.9% Armenians and 23% Azerbaijanis in 1979) and formed the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO).

By refuting the existence of Nagorno-Karabakh, Azerbaijan refutes the fact that Armenians have always been a majority in the territory. Merging Nagorno-Karabakh in wider Karabakh enables Azerbaijan to add the exaggerated number of 1 million (internationally accepted as 650,000) refugees from the surrounding regions to the number of Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh. It is aimed at turning Armenians into a national minority thus preventing them from forming their own self-governance bodies.

Moreover, it will also help Azerbaijan to formalize and make irreversible the occupation of Shushi and Hadrut. Azerbaijani Armed Forces have also launched new military escalations and crossed the line of contact in the areas of responsibility of Russian peacekeepers in violation of November 2020 ceasefire statement in three rounds, capturing new villages, strategic mountains and hills in Hadrut region in December 2020, Askeran region in March 2022 and near Lachin in August 2022. It has generated concern that it is aiming to “integrate” the rest of Nagorno-Karabakh piece by piece, establishing military control over its territory that will result in ethnic cleansing.

Claiming Restoration of its Territorial Integrity

Azerbaijan has aimed to legitimize its initiation of the 2020 Artsakh War by the necessity to restore its territorial integrity while the Armenian side bases its position on the right to self-determination of the Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh. Armenians have also claimed that Armenia has recognized the territorial integrity of Azerbaijan by joining the Commonwealth of Independent States. At the same time, Armenians have pointed out that Nagorno-Karabakh was never part of independent Azerbaijan but was forcibly incorporated into Soviet Azerbaijan as an autonomous region—Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO)—by the Bolsheviks. Nagorno-Karabakh declared independence from the Soviet Union upon its dissolution in 1991, in line with the Soviet Constitution and the 1990 Law on Secession. The OSCE Minsk Group co-chairs have not considered Nagorno-Karabakh as part of Azerbaijan but a territory the status of which must be determined based on compromise. In general, the contradiction of the principles of territorial integrity and self-determination reflected in the UN Charter and the OSCE Helsinki Final Act has been one of the most difficult dilemmas in international law.

Even if we accept that Nagorno-Karabakh is considered part of Azerbaijan by most of the international community, each state has a responsibility to protect its civilian population and ensure their rights, including minorities, and not to conduct ethnic cleansing through massacres, military operations or expelling, or depriving them of fundamental human rights. The notion of territorial integrity has not given a green light to any state to oppress an ethnic group under its jurisdiction. In accordance with the UN General Assembly Resolution 2625 (XXV) adopted in 1970, “every State has the duty to refrain from any forcible action which deprives peoples […] of their right to self-determination and freedom and independence […] The use of force to deprive peoples of their national identity constitutes a violation of their inalienable rights and of the principle of non-intervention.”

During the First Nagorno-Karabakh War, Azerbaijan captured and ethnically cleansed the Martuni region of Nagorno-Karabakh. As a result of the 2020 Artsakh War, Azerbaijan violated the integrity of Nagorno-Karabakh occupying and ethnically cleansing Shushi and Hadrut––parts of the former NKAO. The official representatives of the United States and France refused to visit Shushi back in August, thus expressing their position towards its illegal occupation, which Aliyev’s assistant Hikmet Hajiyev has assessed as disrespect of its territorial integrity by Azerbaijan.

The references of Azerbaijan to the UN Security Council Resolutions adopted on the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict in 1993, reaffirming the territorial integrity of Azerbaijan, are manipulated since they refer to the surrounding regions without determining the final status of Nagorno-Karabakh. Besides, Azerbaijan has violated their provisions that urge “to refrain from any action that will obstruct a peaceful solution to the conflict.” For comparison, UN Security Council Resolution 1244 has confirmed the territorial integrity of the Former Yugoslavia and Kosovo as part of it; however, in 2010 the International Court of Justice concluded that “the declaration of independence of Kosovo adopted on February 17, 2008 did not violate international law.”

Azerbaijanis refer to the fact that during the period of the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Armenians of Nagorno Karabakh were fluctuating between their claims for independence and unification with Armenia. It doesn’t make their self-determination claim illegitimate. In the same manner, after announcing independence in 1991, recognized only by Albania, the Kosovo Liberation Army was seeking the creation of a Greater Albania.

Azerbaijan claims that Armenian support for Nagorno-Karabakh is a territorial claim to Azerbaijan. However, it is not a territorial dispute between the two countries but an issue of self-determination of Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh. Armenia has neither the right nor the leverage on Nagorno-Karabakh Armenians to decide their future. The official positions of the Republic of Armenia and Artsakh authorities don’t always coincide––especially obvious in 2022. The local authorities of Nagorno-Karabakh have repeatedly stated they would not accept to be under Azerbaijan’s control. The right of Nagorno-Karabakh Armenians to determine their future has been recognized by major Western interlocutors, in particular by U.S. Ambassador Lynne Tracey in May and Special Envoy Toivo Klaar in June 2022.

Denying Special Status for Armenians

According to Aliyev, even autonomy for Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh is out of the question. This repeats Azerbaijan’s decision to abolish NKAO in 1991, aiming to bring it under the direct control of Azerbaijan, and resembles the 1989 decision of Serbian President Milosevic to reduce Kosovo’s autonomous status followed by the oppression of ethnic Albanians there that resulted in a violent conflict.

The justification for it is that Armenians are no different from other national minorities of Azerbaijan. Baku claims that If Azerbaijan grants special status to Armenians, it should grant it also to other minorities. As an authoritarian country, it aims to keep its centralized nature.

Aliyev has tried to claim that Azerbaijanis have historically constituted a majority in the NKAO. This claim contradicts all Soviet demographic statistics that demonstrate that Azerbaijanis were only 4% of the NKAR’s population in 1921, when the region was handed over to Azerbaijan. The highest proportion of Azerbaijanis was 22.98% in 1979.

Aliyev has also stated that there are only around 20-27 thousand Armenians left in Nagorno-Karabakh after the 2020 war. This has been refuted by Nagorno-Karabakh authorities, according to whom the current number of its population varies between 100-120 thousand.

These narratives fail to explain why Armenians were granted special status even by the Soviet authorities. Armenians in Karabakh formed entities such as melikdoms in the 15-19th centuries. Azerbaijan also doesn’t mention what happened to Armenians in Nakhichevan, where they constituted such a significant majority that it was also a disputed territory between Armenia and Azerbaijan before the establishment of the Soviet Union, and was gradually and entirely depopulated from Armenians. It also doesn’t mention massacres of Armenians, such as those in Shushi in 1920, Sumgait and Kirovabad (now Ganja) in 1988 and Baku in 1990, Operation “Koltso” (Ring) that ethnically cleansed Shahumyan, Getashen and Martunashen in 1991. Finally, the authorities of Azerbaijan ignore the right of Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh to self-determination in violation of the UN Charter and the Helsinki Final Act.

Even after Pashinyan referred to the need of “lowering the bar of status”, Azerbaijani authorities did not offer any status to Nagorno-Karabakh and did not attempt to address uncertainties transpiring from lack of guarantees for their security and human rights. As for Azerbaijani experts, they are divided into two groups, creating a deceptive perception of an alternative between no status at all and a vague cultural autonomy. For instance, the model of Aland Islands seems superficial and ingenuine, since Azerbaijan, one of the most autocratic countries in Eurasia, cannot be compared with the most democratic Northern European countries.

It is not excluded that Azerbaijan is playing hardball in order to make Armenians agree to vague cultural autonomy for Nagorno-Karabakh under the pressure of the international community. Azerbaijan’s rejection of any status only strengthens the resolve of the Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh not to accept Azerbaijani jurisdiction over them.

Claiming Readiness to Grant Cultural Rights to Armenians in Karabakh

Instead of offering governance models and guarantees for human rights to Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh, Azerbaijan has only made a vague promise that if Armenians accept Azerbaijani citizenship, they can stay and have the same cultural and social rights as other citizens of Azerbaijan.

This sounds like a threat more than an offer or demand to assimilate by Azerbaijan, an autocratic state with an abysmal record of respect for human rights. What will happen to them if they do not accept Azerbaijani citizenship? Will they be massacred or deported from their native land, or allowed to stay without rights and freedoms? And how about the political rights and civil liberties of Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh who have conducted several rounds of elections and formed their governance institutions?

Freedom House assessed not only Armenia but also Nagorno-Karabakh as much more democratic than autocratic Azerbaijan. In spite of its increased isolation, Artsakh is much more democratic than Azerbaijan, which makes placing it under the jurisdiction of Azerbaijan extremely problematic.

Simultaneously, Azerbaijan has been depriving Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh of social and cultural rights by creating a humanitarian crisis in February and March 2022, destroying and appropriating Armenian cultural heritage and distorting history, as presented in Armenia’s ICJ claim; therefore, the promise for social and cultural rights is neither genuine or trustworthy. It seems Azerbaijan understands cultural rights as only a right to learn Armenian language with textbooks prepared in Baku, as stated by an Azerbaijani expert during a peacebuilding event.

Refusing Dialogue With Yerevan and Stepanakert

Azerbaijan claims that it has nothing to discuss with Armenia in relation to the rights and security of the Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh since it is a domestic issue to be managed by Baku, and Armenia should not intervene. At the same time, it has refused dialogue with elected leaders of Artsakh governance institutions.

Some imply that since Armenia has lost its role as Nagorno-Karabakh’s security guarantor and Russia has taken that role over through its peacekeeping contingent; it has become an issue between Russia and Azerbaijan. However, in the absence of international involvement in Nagorno-Karabakh, its exclusion from the negotiations process, and the lack of dialogue between Baku and Stepanakert, Armenia has a moral obligation to remain a diplomatic agent for Nagorno-Karabakh. Armenia also continues to economically subsidize Artsakh in the absence of international assistance to the territory. Azerbaijan must not further isolate Nagorno-Karabakh by aiming to prevent the support and assistance of Armenia to Nagorno-Karabakh that has been always envisaged in all proposals for the resolution of the conflict.

Azerbaijan also needs to start dialogue with the Nagorno-Karabakh authorities. Recently Azerbaijani authorities have been in contact with Secretary of Security Council of Artsakh Vitali Balasanyan over the issues along the Lachin corridor, as well as with local authorities in the north of the territory in relation to water management in the Sarsang water reservoir. However, that dialogue should pursue an agenda of mutually beneficial cooperation and compromise and not an intention of dominance and assimilation, nor pressure for new concessions from Artsakh Armenians who have already lost viable resources, such as access to water resources in Kelbajar.

Demanding to Dissolve the Defense Capacity of Nagorno-Karabakh

The Azerbaijani side has also been demanding the withdrawal of the “remnants of the Armenian army and illegal Armenian armed groups.” As Pashinyan stated on August 4, 2022, currently no military servicemen of the Republic of Armenia serve in Nagorno-Karabakh. Azerbaijan is aiming to target the local self-defense capacity. However, the November 2020 statement does not refer to the defense force of Nagorno-Karabakh but only to the Armed Forces of the Republic of Armenia. All proposals in relation to the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict between the two wars have envisaged the continuing existence of the local defense force.

Moreover, such an ultimatum contradicts international norms. In the UN context, self-defense groups are accepted actors of the security sector. Even in large UN-mandated peacekeeping missions, extreme caution is taken not to dissolve self-defense groups or conduct disarmament of only one side of a conflict. It is even more unacceptable to disarm the victimized party of the conflict, while the perpetrator has much higher military capabilities, is aggressively continuing to arm further, and systematically provokes military escalations, especially before a comprehensive peace agreement and reconciliation.

The Artsakh defense force has not initiated any aggression but has only defended its civilian population. In order to stigmatize it and justify their own military actions, Azerbaijani authorities make frequent allegations about provocations by them. However, it is obvious that the Artsakh defence force has no interest in provoking new military offensives by the Azerbaijani Armed Forces with much higher capability. Nagorno-Karabakh is encircled by Azerbaijani’s gradually advancing military positions, deploying military technologies and equipment, and building dual-use airports. The Artsakh defense force does not have the capacity to constitute a threat to Azerbaijan, and the demand to dissolve it belies an intention either to deprive Armenians of their modest defense capacity or to launch a new military offensive in Nagorno-Karabakh. In both cases, it will eventually lead to the ethnic cleansing of its civilian population.

Aiming to Force Russian Peacekeepers Out Without Letting International Peacekeepers In

Azerbaijan has repeatedly implied that the Russian peacekeeping contingent is located in Nagorno-Karabakh temporarily and has aimed to delegitimize them by military actions and public diplomacy. It seems to be preparing to demand their withdrawal at least at the end of its current term in 2025, but possibly earlier.

The Russian peacekeeping force doesn’t have a mandate from an international organization and its rules of engagement and efficiency are unclear. At the same time, Azerbaijan is not willing to accept an international peacekeeping force whether with the UN, OSCE, EU or other mandate. Only a few Azerbaijani experts discuss the deployment of international peacekeepers. Azerbaijani representatives have been claiming either that Azerbaijan doesn’t accept any foreign military presence on its soil or that the only acceptable foreign military presence is Turkish forces. It is obvious that Turkish military presence in Nagorno-Karabakh is unacceptable for Armenians due to the history of the Armenian Genocide, the slogan—“one nation, two states”—used by Turkish and Azerbaijani heads of state, as well as Turkey’s direct military support to Azerbaijan during the 2020 Artsakh War.

No comparable contemporary inter-ethnic conflict with high intensity, military aggression and threat of ethnic cleansing has been de-escalated or resolved without international guarantees for security, especially without a comprehensive agreement on the resolution of the conflict without addressing root causes of the conflict and defining the modalities for the way forward. An international peacekeeping mission, preferably under the auspices of the EU, UN or the OSCE is needed in Nagorno-Karabakh to ensure the protection of civilians and the difficult transition from conflict to peace. The international community has a responsibility to protect Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh from ethnic cleansing.

Preventing International Civilian Presence As Well

It is not clear whether any international civilian presence in Nagorno-Karabakh is acceptable for Azerbaijan. Most likely, Azerbaijan will continue to prevent it due to its declared intention to allow entry to the territory only from Azerbaijan and conduct their activities only from their offices in Baku. Moreover, it seems Azerbaijan doesn’t want any direct assistance by the international community to Nagorno-Karabakh but wants to make Armenians in the territory clients of the Azerbaijan central authorities, changing their economic dependence on Armenia to economic dependence on Azerbaijan to exercise its control over them. Economic integration with positive intentions and in a cooperative manner promoted by Thomas de Waal is not considered probable by Armenian analysts.

There has never been any international organization or NGO to contribute to peacekeeping, a political resolution, institution-building or development in Nagorno-Karabakh. It has only received limited humanitarian assistance by the ICRC and HALO Trust. The November 2020 ceasefire deepened its isolation further. Since February 2021, international journalists and NGOs are prevented from entering the territory. Azerbaijan doesn’t allow assistance to Nagorno-Karabakh by the international community in violation of the UN’s “Leave no one behind” principle, while an international civilian presence is needed to help with political dialogue and peacebuilding, to solve humanitarian issues, and to assist with development and institution-building.

Negative Associations With Stigmatized Conflicts

Azerbaijan and its lobbyists have been trying to create associations between the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict and the conflicts in Donbas, South Ossetia, Abkhazia and Transnistria, stigmatizing them as “separatists” that enjoy Russian support. This intensified due to the war in Ukraine. The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict rather fits another group of conflicts – those in Timor-Leste, Kosovo and South Sudan, as they are also based on severe human rights abuses and the threat of ethnic cleansing that have led to the recognition of their remedial rights, including secession. Azerbaijan has seemed especially nervous about the associations with the Kosovo conflict to prevent Western support for Nagorno-Karabakh Armenians and to delegitimize their claim for secession from Azerbaijan based on the threat of ethnic cleansing and severe abuse of human rights.

Armenia itself has failed to use the precedent of Kosovo, the most comparable conflict, even if there were elements of it in the stage-by-stage and Madrid Proposals by the OSCE Minsk Group co-chairs. It did not use the precedents of the 2007 Comprehensive Proposal for the Kosovo Status Settlement and the 2010 ICJ Advisory Opinion on Kosovo’s Declaration of Independence.

Who Was The Aggressor?

Since the First Nagorno-Karabakh War, Azerbaijan has presented itself as a victim of Armenian aggression even as it started both wars, having responded to the self-determination claim of the regional parliament of the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO) and peaceful movement of Armenians with massacres and military offensives. In the absence of international support and given the small size and scarce resources of Nagorno-Karabakh, Armenia took responsibility to defend the Armenian population in the territory to prevent their ethnic cleansing. Armenians established control not only over NKAO but also surrounding territories, subsequently using them both as a buffer zone and bargaining tool. Allegedly, some Armenian leaders were ready to concede them in exchange of a status and security guarantees for Nagorno-Karabakh Armenians at different times. However, Azerbaijan refused proposals for a resolution, instead investing a significant portion of oil and gas profits in strengthening its military capabilities to achieve its maximalist ambitions through military means.

Mirroring the Claims for Ethnic Cleansing and War Crimes

Azerbaijan’s response to the decisions of NKAO’s regional parliament were massacres in Sumgait and Kirovabad (now Ganja) in 1988 and in Baku in 1990. They were followed by Operation “Koltso” (Ring) in 1991, when Azerbaijani authorities, with the support of Soviet troops, deployed tanks, combat helicopters and artillery to kill civilians and empty Getashen and Shahumyan regions in Nagorno-Karabakh, and committed the Maraga massacre in 1992, allegedly in the presence of the Soviet troops.

Azerbaijan has been presenting a mirroring claim about the massacre of Azerbaijanis in Khojalu in 1992. There are different witness accounts and views about what happened in Khojalu both in Azerbaijan and Armenia, varying from an allegation of a “genocide” of Azerbaijanis by Armenians to a “forgery and falsification” of the events. According not only to the Nagorno Karabakh authorities but also Azerbaijan’s then President Mutalibov, Armenians had provided a corridor to Azerbaijani civilians to leave Khojalu. Thomas de Waal, author of “Black Garden” has suggested that the civilian victims at a capture of the settlement of Khojalu became a result of “‘spontaneous’, but not of ‘deliberate’ actions”.[1] In her recent book, Armenian researcher Hranush Kharatyan has explained the preparation and seizing of Khojalu by the armed forces of Nagorno-Karabakh, its defense plans by the Azerbaijani authorities, the processes following the capture, the fate of its population and the reasons for presenting it as a “genocide”.[2] The Azerbaijani side also refers to the displacement of the Azerbaijani population from Nagorno-Karabakh and its surrounding regions as ethnic cleansing. A return of refugees was envisaged by the OSCE Minsk Group but was not enacted due to the failure by parties to agree on key issues, first of them being the status of Nagorno-Karabakh.

When the international community began criticizing Russia for war crimes in Ukraine, Aliyev tweeted that Azerbaijan “did not fight against the civilian population, did not bomb buildings, and did not commit atrocities” referring to the 2020 Artsakh War. However, multiple violations of international humanitarian, human rights and customary law, and policy of ethnic cleansing have been acknowledged not only in multiple reports by Armenian NGOs and the Human Rights Ombudsman, but also by Human Rights Watch and other international watchdogs.

Azerbaijan subjected residential areas and civilian infrastructure to cluster munitions and bombs, ballistic missiles and rocket launchers in the capital Stepanakert, as well as other towns and villages, targeting kindergartens, schools, monasteries and churches, and medical facilities, including a maternity hospital. Women, children and the elderly huddled in basements as makeshift bomb shelters. There is evidence that civilians, military servicemen and prisoners of war (POWs) were subjected to mutilation and decapitation. An unknown number of POWs and civilian captives remain in captivity to this day, having been labelled as saboteurs or terrorists, and are used as a bargaining chip by Azerbaijan to seek concessions from Armenia. Some of them were tortured and killed in captivity, including civilians and even women, and others are undergoing prosecution in violation of Geneva conventions. There is evidence of the torture, mutilation and killing of elderly civilians that stayed behind in their homes in Hadrut. While all civilians had been evacuated from Shushi, those who tried to return to collect their belongings from their houses after the tripartite ceasefire statement were captured and labelled as terrorists. For its part, Armenian forces shelled residential areas in Ganja and Barda causing civilian deaths, allegedly targeting military infrastructure but failing due to the use of old military technologies and proximity of residential areas.

During secessionist inter-ethnic conflicts, displacement of population and violations of humanitarian and human rights law are committed by all sides. The oppressed side may commit them as a reaction, out of a sense of victimhood or revenge. Besides, most liberation movements are carried out not by regular armed forces but irregular self-defense units or liberation fighters who may lack awareness about international humanitarian law, especially in the 1990s. In the comparable conflicts in the Western Balkans, all parties committed war crimes to various degrees. Serbian authorities were assigned more blame due to the higher proportion and intensity of human rights violations that they committed. It seems that the following factors define the attitude of the international community in evaluating the level of accountability of parties for war crimes: Who has initiated them, who has conducted them on a larger scale and what has been the intent. Neither Armenia nor Azerbaijan have ratified the Rome Statute, therefore they are not members of the International Criminal Court. Therefore, only an independent international investigation can define and ensure accountability for atrocities. The current threat of ethnic cleansing of Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh is, however, undeniable.

Conclusion

Azerbaijan’s unconstructive behavior and aggressive rhetoric cannot be normalized by the international community. In spite of their geopolitical as well as oil and gas interests, major international players, especially those who claim to operate in the faith of democracy and human rights should define their red lines and signal their dissatisfaction with Aliyev’s rhetoric. So far, international players have been mostly adhering to a policy of parity in their statements, urging both sides to refrain from inflammatory rhetoric and military escalations.

Any further military aggression by Azerbaijan in Nagorno-Karabakh or against Armenia proper should be prevented. If Azerbaijan carries out more ethnic cleansing in Nagorno-Karabakh, launches a major military offensive against sovereign Armenia or continues to apply military blackmail to achieve its maximalist demands, not only Azerbaijan but also the entire international community will suffer a huge reputational loss, constituting another major blow to the international order.

Negotiations aimed at normalization of relations between Armenia and Azerbaijan should seek a comprehensive resolution of the problems between parties, address their root causes, provide long-term solutions and build confidence towards genuine reconciliation and sustainable peace.

Footnotes:

[1] De Waal, Thomas. Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War. ISBN 0-8147-1944-9. http://library.asue.am/open/1876.pdf

[2] Kharatyan H., Khojalu “Genocide” and its Mission in the Karabakh Conflict, 2021

Part I

Azerbaijan’s War of Narratives Against Armenians, Part I

After its military victory in the 2020 Artsakh War, Azerbaijan elevated its war of narratives against Armenians to a new and increasingly aggressive level, often accompanied with disinformation.

Read moreAlso see

Part III: What May Happen to Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh

In this next installment of a series on the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, Sossi Tatikyan presents a way forward given the current situation to ensure security guarantees for the Artsakh Armenians and mark progress in the conflict’s resolution.

Read morePart II: What May Happen to Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh

In order to understand what may happen to Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh if appropriate international guarantees for security and human rights are not put in place for them, Sossi Tatikyan presents the evolution of several comparable conflicts.

Read morePart I: What May Happen to Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh

In Part 1 of a three-part series, Sossi Tatikyan analyzes the uncertainties and possible scenarios for Nagorno-Karabakh if Armenia’s leadership goes ahead with the recognition of Azerbaijan’s territorial integrity.

Read moreNew on EVN Report

The EU’s Main Challenge in Armenia-Azerbaijan Peace Talks

If the EU is honest in its commitment to make peace possible in the South Caucasus, then it needs to address Baku’s ongoing anti-Armenian rhetoric and policy of creating permanent tensions on the borders to pressure Armenia for further concessions.

Read moreOf Useful Idiots, Western Supremacists and White Monkeys

The excess symbolic power that comes with “Westernness” explains how some authors and commentators on the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict can get away with the most outrageous gaslighting, at times engaging in outright racism.

Read moreThe Holy Alliance for Getting Out of a Quagmire

Armenia has been facing an impasse since the defeat in the 2020 Artsakh War. It is imperative that Armenians break with defeatism and desolation by putting differences aside and focusing on what is essential: national security.

Read moreUnit 1991: Strategic Technological Applications for the Armed Forces

A training course for young men and women launched in 2019 by the FAST Foundation—Unit 1991—is a new military unit focused on the creation of arms using the latest technologies.

Read moreKafka in Artsakh

Garegin Papoyan’s film “Bon Voyage” manages to recreate a Kafkaesque world in the form of the Stepanakert Airport, where people follow a seemingly unreasonable system, and continue to do their work with incredible persistence, without questioning its meaning.

Read moreNew section on EVN Report

Law & Society

Declaring Income and Assets: Risks and Opportunities

Starting from 2024, the declaration of income and assets will become mandatory for all citizens of Armenia. Araks Mamulyan looks at the advantages and problems of the program.

Read moreGrave Insult: Criminalization and Decriminalization

The amendment that criminalized “grave insult” in Armenia was in effect for only ten months. On July 1, 2022, Armenia’s new Criminal Code decriminalized grave insult after public pressure. Araks Mamulyan explains.

Read moreWhy Are Reforms in Armenia’s Mental Health Sector Being Delayed?

While planned reforms in Armenia’s mental health sector are constantly being delayed, the rights of people continue to be violated. Sona Martirosyan explains.

Read moreDangerous Work: Accidents in the Workplace

Health and security protocols are not always upheld in workplaces in Armenia, often leading to employees getting injured.

Read moreAll Are Equal Before the Law

To be law-abiding you must know the law, and to protect your rights, you must know the current legal norms. EVN Report launches a new series on Armenia’s current legislative and judicial system.

Read more