Introduction and Part I: Armenia

On August 12, 2022, President of Azerbaijan Ilham Aliyev repeated his increasingly intensifying anti-Armenian rhetoric.

Since its military defeat in the First Nagorno-Karabakh War in the 1990s, Azerbaijan has been conducting a proactive campaign of narratives against Armenia, directed at both its domestic and international audiences. After its military victory in the 2020 Artsakh War, not only did Azerbaijan not stop the war of narratives but elevated them to a new and increasingly aggressive level, often accompanied with disinformation.

In Azerbaijan’s undemocratic environment, its civil society and expert community are closely linked with the state authorities and don’t express any obvious dissent. Think tanks associated with state institutions support the Azerbaijani President’s aggressive narratives in relation to Nagorno-Karabakh, territorial claims on Armenia and threats of a new war since December 2020. Moreover, official circles of Azerbaijan often use public diplomacy channels to push some of these narratives. Only a few Azerbaijani activists living in Europe, and transnationally persecuted by the Azerbaijani authorities, express dissent on these issues.

Instead, after its defeat in the 2020 Artsakh War, Armenia mostly failed to push its diplomatic framing of the conflict and its official circles adopted reactive and passive diplomacy while communicating with international audiences. Following this defeat, Armenia’s official narratives became even more reserved and cautious.

Narratives in Relation to Armenia

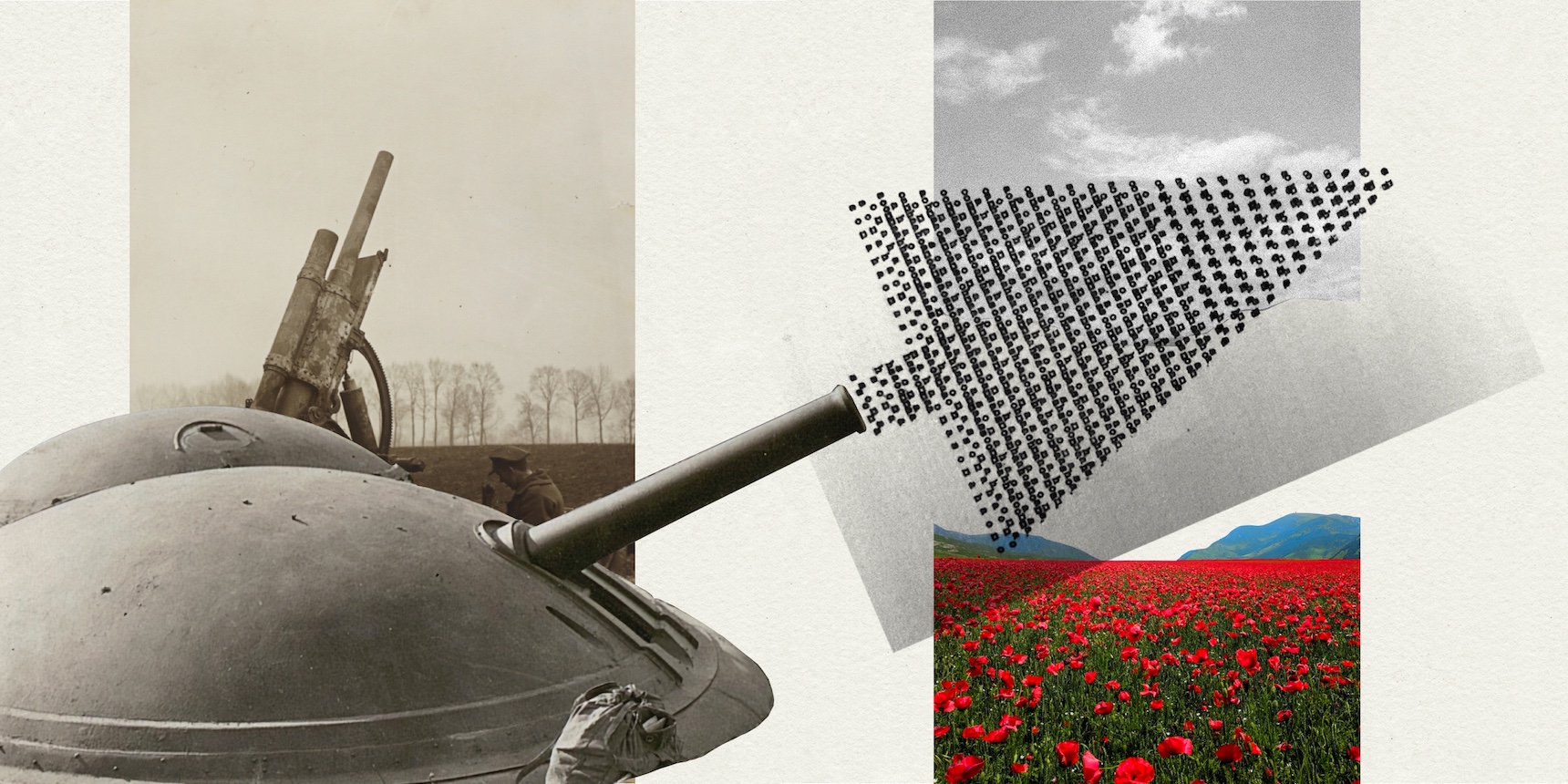

Territorial Claims on Syunik and Other Armenian Regions

Since the November 2020 ceasefire, Azerbaijan has been making territorial claims on different regions of Armenia, especially Syunik [1] but also to the regions of Gegharkunik, Tavush, Vayots Dzor, Ararat and even the capital of Yerevan––most of Armenia proper. These are not only statements as Azerbaijan annexed at least 41 square kilometers of Armenia proper in 2021, and allegedly even more after the disputed Goris-Kapan and Kapan-Chakaten roads were handed over to Azerbaijan under pressure in August 2021 and a number of other areas where Azerbaijani troops have advanced their military positions.

Aliyev acknowledges that Azerbaijani troops have been on the territory of the Republic of Armenia since May 2021. As an excuse, he resorts to a historically distorted justification, claiming that “Zangezur is the land of our ancestors” and urges Armenia to recognize Nagorno-Karabakh as part of Azerbaijan, otherwise it will claim Zangezur.

Throughout 2021, Azerbaijan provoked military tensions and tried to advance its positions in Gegharkunik region and around Yeraskh. It is attempting to take control of Armenia’s main roads, water and other resources to jeopardize Armenia’s internal security, economic sustainability and viability. Well before the 2020 Artsakh War, Azerbaijani experts said during visits to Western think tanks that they intend to make Armenia dependent on Azerbaijan in terms of economy, energy and even security. That is also how Azerbaijan has been officially positioning itself in the post-war period––as a dominant regional actor.

Demanding an Extraterritorial Corridor vs. Opening Communications

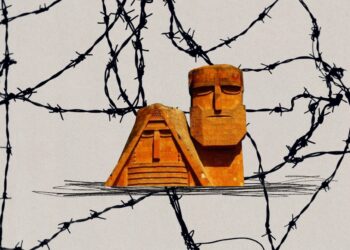

Azerbaijan’s attribution of the same status of the Lachin corridor to the road that is to link Azerbaijan and Nakhichevan is unjustified. Nagorno-Karabakh and Nakhichevan are different entities. Nakhichevan is not an enclave but an exclave under the full jurisdiction of Azerbaijan. Nakhichevan hasn’t had any conflict or security problems since it was given to Soviet Azerbaijan, after which it was depopulated of Armenians. Armenia has not made any claims on it since the Soviet period. Nakhichevan is not isolated; it has trade not only with Azerbaijan through Iran but also with Iran and Turkey. There is an Azerbaijani military airport in Nakhichevan.

Meanwhile, Nagorno-Karabakh is an enclave under threat that was shelled for 44 days less than two years ago. It is subjected to major ceasefire violations by Azerbaijan, and is protected by a Russian peacekeeping force. It is dependent on Armenia in terms of its economy, and has no air connections. Under all iterations of conflict resolution, Nagorno-Karabakh was not meant to be an enclave but had to have a corridor linking it with Armenia. The Lachin corridor cannot be subject to bargaining since its loss will result in the total isolation of Nagorno-Karabakh and will enable ethnic cleansing and precipitate a humanitarian crisis there.

When the Soviet Union was formed, Nagorno-Karabakh and Soviet Armenia were linked. The 1926 map of Soviet Armenia featured in the Great Soviet Encyclopedia shows that Armenia and Artsakh have a common border along the river Aghavnu. Nagorno-Karabakh turned into an enclave after the Soviet authorities established a short-term formation called Red Kurdistan in 1922-1929 under which some lands were taken from Soviet Armenia and retained as part of Soviet Azerbaijan after Red Kurdistan ceased to exist.[2]

The existing route of the Lachin corridor was taken over by Azerbaijan on August 25, 2022, two years earlier than was agreed upon under the 2020 November ceasefire. Currently, Azerbaijan is trying to present the new route, which is under construction, as a road and not as a corridor, and demanding the same status as for the one that will link Azerbaijan and Nakhichevan. However, paragraph 6 of the November 2020 statement clearly indicates that Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh should be linked with a new route along the Lachin corridor. At the same time, it doesn’t use the term “corridor” in paragraph 9 referring to the transport communications linking Nakhichevan with Azerbaijan.

Turkey and Azerbaijan consistently present the idea of a corridor in other forums, such as the Organization of Turkic States, as a way of unifying the Turkic world––a pan-Turkic idea. Moreover the route may block the Armenian-Iranian border, raising concerns not only Armenia but also Iran, as stated by Iran’s spiritual leader Khamenei to the presidents of Turkey and Russia in July 2022.

At the same time, Azerbaijan is using not only the language of sticks but also of carrots, claiming that Armenia has a chance to benefit economically from the so-called corridor after years of economic blockade. However, it is not clear how Armenia will benefit from a corridor controlled by Russian security forces, through which Azerbaijan passes but which Armenia cannot use. Armenia is willing to re-establish roads and railway connections, and has already announced the decision to establish three checkpoints, through which Azerbaijanis can pass. It is Azerbaijan that keeps Armenia in a blockade. If Azerbaijan lifts the blockade, there will be no need for a corridor since the roads will be open.

Finally, the Azerbaijani demand for an extraterritorial “Zangezur corridor” deviating from the November 2020 statement, as opposed to the Armenian offer of opening communications compliant with the statement, harks back to the Danzig corridor from World War II, contradicts the principle of sovereignty of the UN Charter, sabotages negotiations aimed at peace, and generates the potential for another conflict. Locked up territories, closed borders and corridors are not compatible with the contemporary concept of peace.

Demanding Enclaves

During the Soviet period, various parts of Armenia were handed over to Azerbaijan, reducing its territory from the original 30 thousand to 24 thousand sq/km without any legal basis and justification, thus artificially creating Azerbaijani enclaves within Armenia. The Soviet Union had not joined the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and was not keen on taking its principles into consideration. Possibly, corruption among the Soviet political elites played a role as well. After the collapse of the Soviet Union and the First Nagorno-Karabakh War, Azerbaijan lost control over those enclaves, while it captured the large village of Artsvashen from Armenia.

From time to time, Azerbaijani officials and public figures raise the issue of enclaves. Not only did those enclaves not exist during the establishment of Soviet Armenia and Soviet Azerbaijan but also not in the First Republic of Azerbaijan either, to which Azerbaijan declared itself its legal successor.[3] Therefore, making such territorial claims against Armenia contradicts not only the principles of international law and Armenian legislation but also the declaration of independence and constitution of Azerbaijan itself.

The existence of enclaves contradicts modern concepts of international order. Different parts of Armenia cannot be separated from each other, and Armenia’s borders with Georgia must remain intact, along with its borders with Iran, given that Azerbaijan and Turkey have kept Armenia under blockade since Armenia’s independence. Armenia cannot be deprived of its viability. Armenia must have sovereignty over its highways and roads, and control over its natural resources.

Delimitation should be conducted in line with the OSCE Manual on Delimitation and Demarcation, contemporary international law and human rights standards, primary national legislation and those maps that have a legal basis. At the same time, it is preferable to hold the delimitation process with the assistance of an international organization, such as the EU, that has offered its expertise. The use of force contradicts international law and should be excluded. In relation to the most difficult issues, the sides should seek arbitrage in the International Court of Justice.

Distorting History

Since Soviet times, researchers Ziya Bunyadov and Farida Mammadova have attempted to rewrite regional history. Revisionism of history has gradually become a state policy in Azerbaijan, rooted also in its education system. Moreover, in the spirit of mirroring, Azerbaijan also claims that it is Armenia that has distorted the history of the region.

Currently, Azerbaijani historians are attempting to claim that Armenians are not native to Nagorno-Karabakh but moved there during the Russo-Persian war in the 19th century. This contradicts historical records and consensus among international historians according to which Artsakh has been Armenian since ancient times. Azerbaijanis claim that Armenian cultural heritage, such as monasteries and cross-stones in Nagorno-Karabakh are Caucasian Albanian, Udi, Russian Orthodox—anything, except Armenian. This distortion has been included in Armenia’s claim to the ICJ, which has ordered a provisional measure urging Azerbaijan to refrain from the practice, and in reports of international organizations such as PACE.

Moreover, Azerbaijanis have even started claiming that Armenians are not native to Armenia proper and the Caucasus in general, again contradicting historical consensus. They have been referring to a person who has a surname with an Armenian ending – Philip Ekozyants, someone unknown in Armenia, and with unverified citizenship and scientific credentials, who is spreading these historical narratives through videos in Russian.

Mirroring the Armenian Charges of Ethnic Hatred

The Azerbaijani president, public figures and security forces have been spewing xenophobia and discrimination toward Armenians, manifested both by hate speech and actions. Armenia did not use international legal mechanisms between the first and second Nagorno-Karabakh wars, except in the European Court of Human Rights, which has limited implications. It made its first claim to the ICJ in relation to Azerbaijan’s violations of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD) in September 2021. This was immediately followed by a reciprocal case by Azerbaijan. The ICJ issued provisional measures for the implementation of both parties on December 7, 2021.

The measures are mainly addressed to Azerbaijan requiring it to refrain from degrading treatment and torture of Prisoners of War, destroying Armenian cultural heritage, distorting history and inciting ethnic hatred towards Armenians, while also requiring Armenia to prevent the incitement of ethnic hatred. However, there is a subtle difference in the last requirement common for both parties: the order against Armenia refers to incitement of racial hatred “including by organizations and private persons” while the order against Azerbaijan says incitement of racial hatred or racial discrimination “including by its officials and public institutions.” This reflects the fact that such hatred is systematically promoted by the top leadership of Azerbaijan while in Armenia it is propagated by ultranationalist groups and individuals.

Stigmatizing Armenian Authorities as Simultaneously Pro-Russian and Pro-Soros

While maneuvering between all major actors in the region, including Russia, Azerbaijan has tried to stigmatize Armenia aiming to conduct complementary or multi-vector policy as a Russian proxy between the first and second Nagorno-Karabakh wars. Recently President Aliyev hasn’t done it publicly due to his close relations with Russian President Putin but Azerbaijani experts continue to do it through public diplomacy channels. As Armenian PM Pashinyan stated, Aliyev has been labelling Armenia as pro-Russian to the West and as pro-Western or under Soros’ influence to Russian interlocutors.

Azerbaijan signed a declaration elevating its cooperation with Russia to an alliance only one day before the start of the war in Ukraine. At the same time, Azerbaijan offered gas to Europe to secure a portion of alternative sources to Russian gas in July 2022.

Azerbaijan and Armenia have been voting similarly—either neutral or abstaining—in the votes in relation to the war in Ukraine since March 2022; however, it is much more courageous for Armenia not to vote pro-Russian, given Armenia’s CSTO membership and especially, the presence of the Russian peacekeeping mission in Nagorno-Karabakh than for Azerbaijan. Moreover, Armenia’s foreign policy has demonstrated increasing tendencies of diversification since the start of the war in Ukraine through paying visits to the U.S., EU member states, EU and NATO HQs, as well as receiving missions from the senior officials of the U.S. and EU countries.

Azerbaijan is aiming for the withdrawal of the Russian peacekeeping contingent at least by 2025 and possibly earlier. It is possible that it will try to accomplish it not by “opening a second front” as some were hoping in light of the war in Ukraine, but by making a deal with Russia. There is frustration among Armenians with the failures of Russian peacekeepers to prevent ongoing Azerbaijani aggression. Since May 2022, there is also a striking contradiction between the positive stance of the U.S. and France on one side and the negative stance of Russia on another in relation to their willingness to resume their mediation of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict within the OSCE Minsk group to be elaborated in Part II of this article. On August 28, Azerbaijani authorities made offensive statements against the U.S. and France, slamming them for their reluctance to visit Shushi, and their attempts to revitalize the OSCE Minsk Group. Thus, Azerbaijan’s attempts to present itself as more pro-Western than Armenia is invalid.

Accusing Western Organizations of Biases

Azerbaijanis claim that “Western organizations”, such as PACE or Freedom House are biased and pro-Armenian due to the alleged influence of the Armenian diaspora and the presence of some Armenian staff members. They refute the credibility of international watchdogs rating Azerbaijan as undemocratic and Armenia as democratic, pointing to the increased popularity of Aliyev since the 2020 war. At the same time, over the last two decades, Azerbaijan has sponsored its experts’ work in Western think tanks. Moreover, it has institutionalized bribery in the form of the “Azerbaijani Laundromat,” and caviar diplomacy with the goal of shaping foreign policy in its favor.

In contrast, Armenians believe that international actors apply double standards, bothsidism and false equivalence based on geopolitical interests, and ignore oil-rich Azerbaijan’s military aggression against Armenians accompanied with human rights violations. The recent gas deal between the EU and Azerbaijan intensified those concerns.

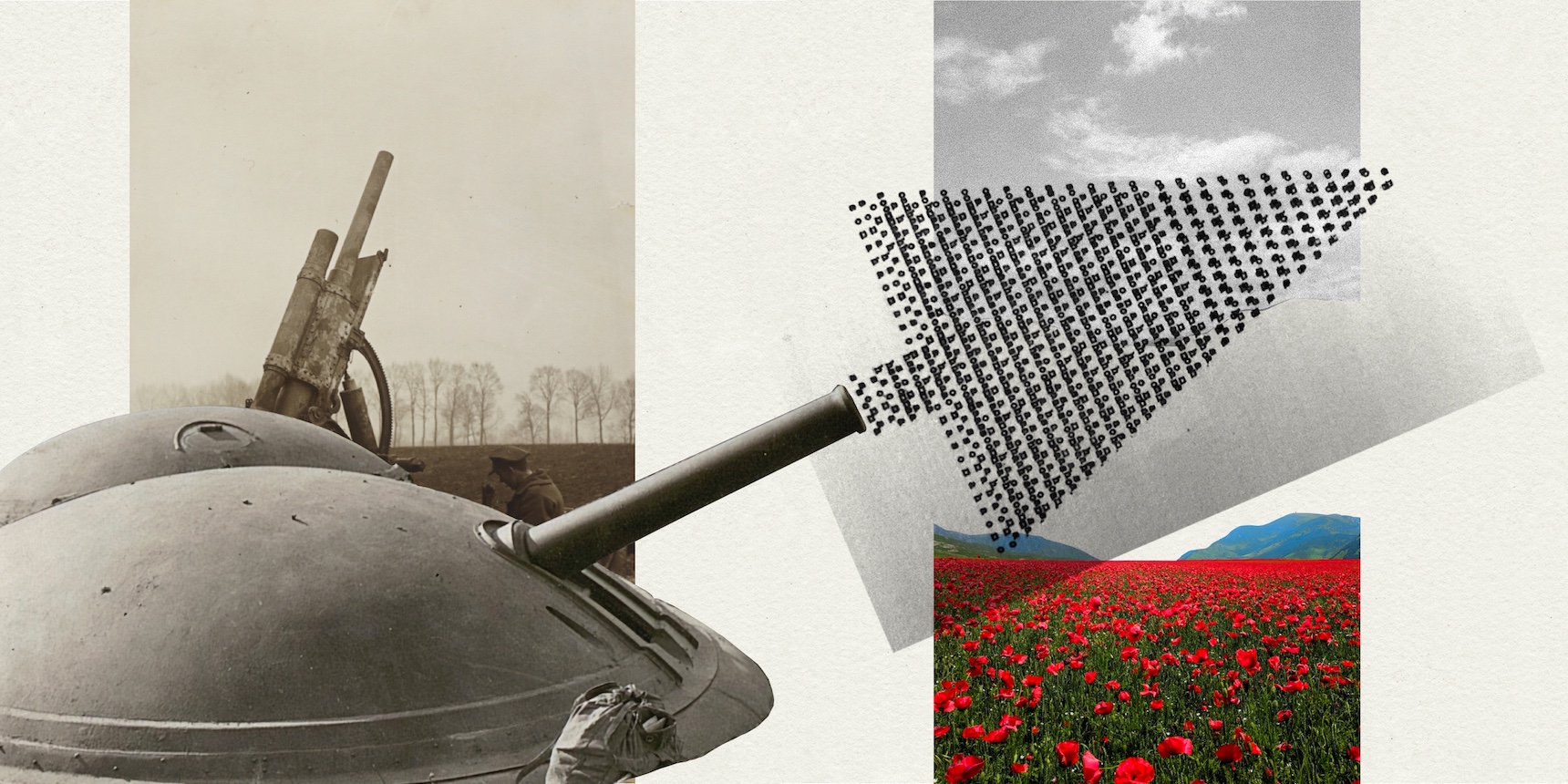

Military Blackmail

Aliyev says that If Armenians don’t agree with maximalist Azerbaijani requirements and continue to raise the issue of Nagorno-Karabakh, Azerbaijan will launch another war and destroy both Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia. He implies that the Armenian army is in poor shape, and thus Armenians should accept the situation and all Azerbaijani demands. At the same time, Aliyev has threatened that if Armenia tries to restore its armed forces or get access to new modern weapons, Azerbaijan will immediately launch a military offensive and destroy it.

At the same time, Azerbaijan has perpetrated three rounds of major and many minor violations of the 2020 ceasefire statement, and advanced its military positions in Nagorno-Karabakh, capturing strategic hills and depopulating villages, and conducting creeping annexation of border regions of Armenia. It is aggressively building up its military capabilities, including dual-use airports near the contact line in Nagorno-Karabakh and the borders with Armenia, actively arming and conducting military exercises with Turkey and Pakistan.

Azerbaijan’s threats violate fundamental principles of the UN Charter: Article 2(4) prohibiting the unilateral use of force, except for self-defense, and Article 51 on the individual and collective right of each country to self-defense. Moreover, each country has an obligation to protect its civilian population. Additionally, imbalance and asymmetry between parties to a conflict generate a potential for a new one, and military balance serves as deterrence. There is a need to restore the military balance between Armenia and Azerbaijan, and major international actors must contribute to it.

Claiming That Azerbaijan Offers Peace

Armenian authorities have been reconciliatory and advocated for peace through reaching compromise and making concessions in spite of domestic dissent. They have also adopted consistent language on relevant issues for domestic and international audiences, the West and Russia.

At the same time, there is a clear discrepancy between Azerbaijan’s rhetoric aimed at the international audience on one hand, and domestic audiences on the other. Statements about a peace agenda contradict their territorial claims, militaristic threats and ethnic hatred incited towards Armenians. Any Armenian who disputes Azerbaijani narratives is labelled a revanchist or hardliner.

Azerbaijan doesn’t take responsibility for its non-implementation and violations of the November 2020 statement and instead accuses Armenians of not implementing or violating it. For instance, it makes frequent statements accusing Armenian or Nagorno-Karabakh defense forces for provoking Azerbaijani armed forces before it starts yet another military escalation. It is obvious that neither Armenia nor Nagorno-Karabakh are interested in new military tensions with Azerbaijan, if at least because the current military balance is unfavorable for them.

This also reveals the non-genuine and manipulative nature of the peace agenda by Azerbaijan and its accusations of Armenia rejecting its offer for peace. It is obvious that Azerbaijan is in euphoria after its military victory, trying to capitalize on it, taking advantage of the chaotic geopolitical environment and the fragile state of international order currently in light of the war in Ukraine.

Footnotes:

[1] Old name, Zangezur, which Azerbaijan claims has Azerbaijani origin but Armenian researchers have shown its Armenian etymology.

[2] Rouben Galichian, “Historic Maps of Armenia. The Cartographic Heritage. Revised and Abridged.” (London: Bennett & Bloom, 2014)

[3] Ibid

Also see

Opinion

Of Useful Idiots, Western Supremacists and White Monkeys

The excess symbolic power that comes with “Westernness” explains how some authors and commentators on the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict can get away with the most outrageous gaslighting, at times engaging in outright racism.

Read moreThe Holy Alliance for Getting Out of a Quagmire

Armenia has been facing an impasse since the defeat in the 2020 Artsakh War. It is imperative that Armenians break with defeatism and desolation by putting differences aside and focusing on what is essential: national security.

Read moreSpotlight Karabakh

Where Is Yerevan as Armenian Villages Handed Over?

As the Armenian villages of Aghavno, Berdzor and Sus on the Lachin Corridor were handed over to Azerbaijan on August 25, questions remain about why Yerevan was seemingly excluded from that process.

Read moreTechnological Trends in the 2020 Artsakh War and the 2022 Russo-Ukrainian War

The 2020 Artsakh War and the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian war are the first classic interstate wars in almost two decades involving the regular armies on both sides of the conflict, highlighting trends in warfare, including the effect of the latest technological solutions.

Read morePolitics

Baku’s Unrelenting Violations of the Tripartite Statement

Azerbaijan’s motivations, strategy, manipulation, and attempts to legitimize its every military aggression against Artsakh are gross violations of the November 9, 2020 tripartite statement that ended the 2020 Artsakh War.

Read more“Peace” According to Azerbaijan: What Does It Mean for Artsakh?

Just days after Azerbaijan’s most recent military attack, local authorities in Nagorno-Karabakh instructed residents of the Armenian village of Aghavno to leave their homes by August 25, when it is scheduled to be handed over to Azerbaijani control.

Read moreArmenia and the West: Reassessing the Relationship

The 2020 Artsakh War exposed a number of myths and misconceptions in Armenia and among Armenians toward the West. Taline Papazian reviews some of those misconceptions and outlines current Western engagement in Armenia and the region.

Read moreThe Dictator Has No Clothes: Aliyev’s Regime and Its Declining Oil Revenues

Baku’s oil economy is not sustainable, as diminishing revenues in the long-term increase the probability of domestic instability in Azerbaijan, potentially triggering militarized interstate disputes.

Read morePart III: What May Happen to Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh

In this next installment of a series on the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, Sossi Tatikyan presents a way forward given the current situation to ensure security guarantees for the Artsakh Armenians and mark progress in the conflict’s resolution.

Read morePart II: What May Happen to Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh

In order to understand what may happen to Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh if appropriate international guarantees for security and human rights are not put in place for them, Sossi Tatikyan presents the evolution of several comparable conflicts.

Read morePart I: What May Happen to Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh

In Part 1 of a three-part series, Sossi Tatikyan analyzes the uncertainties and possible scenarios for Nagorno-Karabakh if Armenia’s leadership goes ahead with the recognition of Azerbaijan’s territorial integrity.

Read more

This is an excellent article.

Thank you for pointing out that Nakhichevan is an exclave that already has routes to Azerbaijan proper not only through Iran but through Turkey and Georgia.

Artsakh, on the other hand, has NO routes to Armenia except one under great pressure.

No special route through Armenia from Turkey to Azerbaijan proper is needed by any country since these other routes exist.

Incidentally, Georgia is ALREADY a pan-Turkic route, and it’s supported by the West (backed by Israel) which seeks to conquer the Caucasus.

Russia has betrayed Armenia, of course, not just in 2020, but also now as it (and the CSTO) allow Azerbaijan to occupy parts of Armenia. Russia seeks total control of Armenia.

Let’s remember that without Armenia (Russia’s only ally in the Caucasus)Russia loses the entire Caucasus and Caspian Sea to NATO. Russia knows this. For some very, very strange reason, however, many Armenians do not know this and still think their country matters to no one. Why is this?