Introduction

In Armenia, babies born with disabilities are often rejected by their parents and sent to orphanages or other residential state institutions. Globally, children who end up in such institutions tend to remain there for life; instead of becoming contributors to society, they continue to depend on social benefits (Mutler, Wong, & Crary, 2017). Decades of research have shown that children fare better in every way in a family setting, where they can receive consistent adult attention and engagement (Faith to Action Initiative, 2014). Institutions, even the best-resourced ones, end up harming children and are detrimental to their happiness, development and future.

In Armenia, the three primary reasons for the rejection of babies with disabilities are: (1) the social stigma of having a child with a disability; (2) financial hardship or poverty of the family; and (3) a lack of awareness or information about disability as a whole and the disability of the baby in question. Another important factor is the social pressure exerted on the mother to give up her baby with a disability. This nudge is often applied at the maternity ward, at the behest of healthcare professionals such as doctors and nurses. This social pressure may not be the underlying cause of abandonment but it may be the trigger.

Disability, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations (UN), is part of the human condition, likely to be experienced by everyone, either permanently or temporarily, at some point in their life. Globally, there are around 1 billion people with disabilities. People with disabilities are often poor and the stigma and discrimination they face are common in all societies, including Armenia.

The Armenian government has been taking some positive steps to address the issue. It has, for example, signed and ratified the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) (United Nations, 2006). The CRPD is an important tool to ensure that people with disabilities have access to the same rights and opportunities as everyone else. The CRPD is also important because it does not treat disability as a medical issue but rather as a human-rights concern (see section 1.1.1.), encouraging signatories such as Armenia to place their focus on the barriers that individuals with disabilities face in society. Signatories of the CRPD, including Armenia, are now obliged to promote and protect the rights of people with disabilities.

The Armenian government has acknowledged the avoidable institutionalization of children as a problem. It has been transforming some residential institutions for children into community centers and increasing support for family-based care. However, these programs do not include children with disabilities on an equal basis with other children. As of May 2016, 70 percent of the 670 children registered in orphanages in Armenia have some type of disability. Moreover, existing legislation allows for persons with intellectual disabilities to be deprived of their legal capacity, with no supported decision-making mechanisms in place for these individuals. As a result, many people with disabilities in Armenia remain in institutions for their entire lives (Human Rights Watch, 2018).

The problem of disability is complex and multi-layered. International experience shows there are many different ways to address the issue. More recent international interventions to solve disability issues, however, all have one thing in common – a commitment to changing negative social perceptions around disability. In particular, the fairly recent paradigm shift from viewing disability as a medical issue to understanding it as a social (and human rights) concern is notable and in part an outcome of the CPRD. Thus, all future interventions must align with this paradigm shift. Across the world, intensive efforts are underway to get and keep children out of orphanages transform social welfare systems and attitudes. If families could get the information and services they need as well as the required information to shift attitudes about disability, they would not reject their children in the first place.

Drawing from interviews with Armenian experts, discussions with Armenian mothers of children with disabilities, analyzing Armenian law and legislation and examining statistics and international recommendations, it is clear that social stigma is inextricably intertwined with all the other problems. The lack of adequate financial support for the families of children with disabilities is in large part simply due to it not being a government priority, either because of the Soviet legacy of institutionalising as a solution (thus drawing from and feeding into stigmatisation) or because other social issues always seem to take precedence. The lack of public information about disability in general is an outcome of stigmatization of disability and its lack of visibility. A multi-pronged, long-term campaign to tackle public perceptions of disability in Armenia would ultimately address all the manifestations of the problem. Such a broad approach will eventually be necessary in Armenia but is, unfortunately, outside the scope of this White Paper. This White Paper will argue in favor of a more targeted intervention: (re)training healthcare professionals in Armenia about disability and about how to talk to parents about the news of disability of a child. This particular policy intervention was chosen because it would address the most immediate source of the problem: stigmatization by healthcare professionals, who often apply social pressure on parents to reject their baby. The intervention also addresses healthcare professionals’ responsibility to communicate with parents professionally and without bias. It also corrects parents’ lack of information about disability generally as well as about the disability of their child.

Background

In Armenia, mothers who give birth to babies with disabilities often reject them and send them to orphanages. As a result, most children in Armenian orphanages have at least one living parent (World Health Organization, 2011). In these institutions, these babies and children are segregated from the community and cut off from family – often for life. Armenian children with disabilities frequently remain in institutions as adults indefinitely, stripped of their legal capacity (Human Rights Watch, 2018).

The Government of the Republic of Armenia is taking some positive steps by transforming some orphanages into community centers and supporting family-based care, but it is not including children with disabilities equally in these efforts. According to the National Statistical Committee, there are currently approximately 800 children in six orphanages in Armenia (Gziryan, 2019). While the number of able-bodied children in orphanages has declined over the past twenty years and several orphanages have been closed down over the last 6-7 years, the ratio of children in orphanages with disabilities has grown and specialised orphanages for children with disabilities remain overcrowded.

Global evidence shows that children need more than good physical care; they also need love, attention and an attachment figure with whom they can develop a secure bond based on which all other relationships are built (Williamson & Greenberg, 2010). There is now a great deal of evidence that serious developmental problems arise in children placed in residential care. Institutions negatively impact children, giving way to emotional and psychological disorders such as attachment issues, aggressive or passive behaviour, developmental delays and learning disabilities. They may even jeopardize their physical health. For the past fifty years, child development specialists have acknowledged that residential institutions consistently fail to meet children’s developmental needs for attachment, acculturation and social integration (Williamson J., 2014). Sustained and meaningful contact between a child and a caregiver is almost always impossible to maintain in an orphanage because of the high ratio of children to staff and the nature of shift work. Institutions often have their own ‘culture’ which is often rigid and lacking in basic community and family socialization.

In Armenia, orphanages for children with disabilities have also been the setting for physical and sexual abuse. A 2012 report by Armenia’s Public Monitoring Group highlighted instances of physical violence by orphanage staff members and referenced cases of sexual abuse at facilities for children with disabilities.

1.1. Understanding Disability

Disability is understood by international experts to be part of the human condition. Everyone is likely to experience it, either permanently or temporarily, at some point in their life. According to the United Nations, “Persons with disabilities include those who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments which, in interaction with various barriers, may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others” (United Nations, 2006). This fluid definition accommodates different understandings of disability or impairment but, by defining disability as an interaction, it clarifies that disability is not an attribute of the person (World Health Organization, 2011). An impairment on its own would not lead to disability if there was a completely inclusive and comprehensively accessible environment (Christian Blind Mission, 2015). Thus, it follows that addressing attitudinal barriers such as stereotypes, prejudices and other forms of paternalistic and patronising treatment against people with disabilities would address a large part of what is debilitating about disability. This idea is also recognized in the Preamble of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD): “…disability results from the interaction between persons with impairments and attitudinal and environmental barriers that hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others” (United Nations, 2008).

In line with this concept, the global disability movement has persuaded public opinion to use the term “person with disability” rather than “disabled person” in order to put the focus on the person first and the disability as a secondary characteristic. This is why “children/babies/individuals with disability” is the terminology used throughout this white paper.

In Armenia, the full institutionalisation of babies and children with disabilities has been the norm since the Soviet era. Soviet state practice officially recognized persons with disabilities as “dependents” while simultaneously promulgating “defectology” – a Soviet discipline that, despite some positive intentions, imbued people with disabilities in a deep stigma. Within this framework, the solution to disability was the removal of these children from society for institutionalization. Thus, many children with disabilities were shut away in institutions from birth, later “graduating” to adult institutions. This stigma that was both the result and cause of this approach continues to influence contemporary public attitudes in Armenia towards disability. Along with a lack of proper information, it leads to decisions that are detrimental for children with disabilities.

1.1.1. Models of Disability

A major paradigm shift has been informing the way disability is understood globally. Consequently, it has impacted which interventions are seen as most appropriate. In particular, there has been a shift from a “medical” understanding of disability to a “social” or “human rights” understanding. The older medical model focuses on managing the illness or disability itself. The social and human rights models view the problem of disability as being situated not within the individuals with disabilities but within societal attitudes towards them, including a lack of accommodations in the physical environment (e.g. accessibility of public transportation and buildings). In the social model, the main barriers to equality for people with disabilities are the negative social attitudes toward disability in their communities and the lack of physical accommodations (Shakespeare, 2006). The human rights model focuses on human dignity, considering people as valuable not only because they are economically or otherwise “useful,” but because of their inherent self-worth. The human rights model puts the individual at the center and locates the main problem of disability in society as external to the person. As a result, approaches to disability issues that combine the social and the human rights aspect are becoming standardized internationally.

The medical model focuses on the individual and sees diasability as a health condition and an impairment of the individual. It assumes that addressing the medical ailment will resolve the problem. In this approach a person with disability is primarily defined as a patient requiring medical intervention. Disability is seen as a disease or defect that is at odds with the norm and that needs to be fixed or cured (CBM, 2017).

The social model considers that the problem lies with society; that due to social, institutional, economic or political barriers people with disabilities are excluded. This approach focuses on reforming society, removing barriers to participation, raising awareness and changing attitudes, practice and policies (CBM, 2017).

The right-based model is based on the social model and shares the same premise that society needs to change. this approach is founded on the principle that human rights for all human beings beings is an inalienable right and that all rights are applicable and indivisible. It takes the CRPD as its main reference point and prioritises ensuring that state officials at all levels meet their responsibilities. This approach sees people with disabilities as the central actors in their own lives as decision makers, citizens and right holders. As with the social model, it seeks to transform unjust systems and practice (CBM, 2017).

EVN Report’s the Reader’s Forum section is meant to create a space and platform for readers to be co-creators of engaged, credible journalism, to have a voice in driving policy development and to collaborate in bringing about a more informed public discourse. We want you, our reader, to be part of the conversation and that is why we are inviting you to read our White Papers, leave a comment, ask a question, make a recommendation and be part of the conversation.

Transitional Justice

Armenia Gets Serious About Reforms: Making Sense Out of Vetting

As an instrument of transitional justice, vetting is designed to “cleanse” state institutions that are tainted by systemic corruption, nepotism, and incompetence. Vetting of personnel is the first step toward the broader goal of institutional reform, writes Dr. Nerses Kopalyan.

Read moreTransitional Justice Agenda for the Republic of Armenia

Should Armenia implement the tools of transitional justice? This White Paper, developed by Dr. Nerses Kopalyan is a comprehensive transitional justice agenda for the Republic of Armenia.

Read moreFoster Care

Future Prospects for Foster Care for Children with Disabilities in Armenia

A child’s right to family life is enshrined in Armenian and international legal documents and considered a priority in Armenia’s 2017-2021 Strategic Plan on the Protection of the Rights of the Child. Here is EVN Report's White Paper about specialized foster care for children with disabilities.

Read moreMy Big and Unusual Family: SOS Children’s Villages

The Kotayk SOS Children’s Village was established in 1988 following the Spitak earthquake to offer immediate aid to those children who had lost their parents. Today, over 30 years later, SOS Children’s Villages continue to support children and their families in three locations across Armenia.

Read moreVolunteerism

Volunteering in Armenia: Key Issues And Challenges

This policy analysis aims to explore the main reasons people volunteer, how volunteer work is regulated and the key issues the volunteering sector faces in the Republic of Armenia.

Read moreVolunteering Doesn’t End With the Volunteer

Volunteerism not only contributes to the social wellbeing of the volunteer, but also greatly benefits the communities and societies where it takes place, ensuring sustainable capacity development and building social capital. In Armenia, there is currently no legal framework regulating volunteerism.

Read moreIt is important to note that medical services may still have a significant role to play in supporting the quality of life for some people with disabilities – as they do with some people who do not have disabilities – but this relationship must not be the basis on which people with disabilities are defined. Rather, people with disabilities should be seen as individuals with abilities, aspirations and gifts who should not be limited or categorized by their impairment. Moreover, any medical service that is offered must be based on respect for the choice of the individual with disabilities.

1.2. Main reasons for the institutionalization of babies with disabilities in Armenia

According to various sources, including interviews and conversations with Bari Mama NGO representatives, two mothers of children with disabilities, the head of Yerevan’s Mankan Tun orphanage, a representative of the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs, a representative of the Republican Institute of Reproductive Health, Perinatology, Obstetrics and Gynecology and academic literature, the main reasons for rejecting a baby with disabilities in Armenia are: (1) social stigma; (2) financial hardship; and (3) lack of information/awareness about disability generally and the baby’s disability specifically. A significant aspect of the problem is also the social pressure exerted on the mother, which, in the context of social stigma and the absence of unbiased information, makes the transfer of the child to the orphanage seem easier and more appropriate.

1.2.1. Social stigma

Individuals with disabilities face stigma and discrimination in Armenia from society at large, from healthcare professionals on whom they rely for healthcare and even their own parents – all from the moment they are born. This stigma follows them throughout their lifetime. In Armenia, many parents of children with disabilities describe, for example, instances where their children experienced harassment and bullying at mainstream schools (Human Rights Watch, 2017).

Stigmatization leads to social exclusion and negatively impacts quality of life. As a result, people with disabilities may be left out of social activities, presumed to be helpless, unable to care for themselves or to make their own decisions. People with one disability, such as a physical impairment, may be incorrectly presumed to have other disabilities, such as an intellectual disability. According to Armenia’s Ombudsman, people with disabilities in Armenia can be denied jobs, education, housing or other opportunities based on false assumptions or stereotypes about disabilities (Human Rights Defender of the Republic of Armenia). This social stigma feeds into and reinforces the belief that a child with disabilities cannot be integrated into society.

In Armenia, social stigma also involves a strong sense of shame associated with disability. In a 2016 interview with Human Rights Watch (HRW), a respondent in her early 20s said that part of her decision to give up her 4-year-old son with cerebral palsy to an orphanage was the shame that it might bring to her brother, who was yet to be married. “The issue for us was not entirely finances. We have to think about the bigger family. My brother is still young. We are thinking about a potential bride for him. No one will want to see an unhealthy child at [our family’s] home.” (Human Rights Watch, 2017). The implication is that the child’s presence advertises, rightly or wrongly, that her brother’s genes may be predisposed to produce another child with a disability. The resulting social reactions and prejudice are often more debilitating than the disability itself.

1.2.2. Poverty/lack of financial resources

Parents in Armenia are often in a state of extreme financial hardship and reject the baby because they cannot provide the minimum care necessary for life. UNICEF research on disability across Central East Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States confirms that a primary reason why families surrender their children with disabilities is a lack of care-giving capacity (UNICEF, 2013). According to the Government of Armenia, poverty rates in Armenia have been gradually decreasing since 2009, alongside an increase in public funding by the Armenian state. As a result, the overall number of children in orphanages began to drop in 2010. While these statistics are encouraging, state budget allocations for people with disabilities remained unchanged over the same time period (Government of the Republic of Armenia, 2011).

Direct costs associated with caring for a child with disabilities can be prohibitive for families. Beyond the chronic conditions of children with disabilities that may need medication or medical and rehabilitation services, which are covered by the state, there are often additional needs, such as special food, supplies, adjustments in housing, aids designed and adjusted to personal needs, accessible transportation and extracurricular services.[1] Moreover, raising a child with a disability increases family expenditure while simultaneously reducing opportunities to earn income. Consequently, families with children with disabilities are usually poorer than others (Parish, Rose, Grinstein-Weiss, Richman, & Andrews, 2008; Ejiri & Matsuzawa, 2017). The higher poverty risk can amplify the disabling effect of a child’s impairment and affect the family’s ability to support themselves. Many hours of unpaid care are involved and parents spend a great deal of time managing the impairing aspects of their child’s life. In Canada, research shows that parents of children with disabilities spend 50-60 hours per week on tasks related to the disability (Roehr Institute, 2000), more than the equivalent of a full-time job, underlining the fact that there is a need to support the whole family, not just the child.

Highlighting the intersection of poverty and rural life in Armenia, 70-80 percent of the mothers that abandon their children with disabilities are from Armenia’s regions (outside the capital city, Yerevan). According to a representative of the Bari Mama NGO, state support is often insufficient for rural families as the treatment, transportation and care of children with disabilities are costly. There are not sufficient medical services outside Yerevan, forcing parents to bring the baby to the capital. Taxis, often the most convenient mode of transportation, is a large expense for many of these families.

1.2.3. Lack of information/awareness

The third reason for rejecting a baby with a disability is the parents’ lack of awareness and access to information. This includes a lack of information about disability generally, incorrect or incomplete information about the disability of their baby specifically, as well as the lack of information about all the opportunities and services available to support families with children with disabilities (Gziryan, 2019).

The lack of information about parenting a child with disabilities is rooted in the general lack of knowledge about all aspects of reproductive health among significant portions of Armenia’s population. Many women in Armenia do not attend all the medical examinations recommended during the course of pregnancy and thus may miss the opportunity to discover a disability before birth. According to an Armenian healthcare worker, it is impossible to force the woman to attend all the suggested medical examinations; many women only come to a doctor at childbirth. Still, even if all women undergo prenatal check-ups, many physical and mental disabilities are not possible to detect, making the element of surprise and unpreparedness about a baby’s disability difficult to avoid. Without adequate information about the possibility of disability as part of the overall preparation for birth, or about what a specific disability might mean for a given baby, the mother lacks the necessary information and is not prepared to make an informed decision, leaving her more vulnerable to social pressure.

Doctors and nurses in Armenia also bear responsibility for providing incorrect or incomplete information to a mother after birth regarding what disability is and what the prospects for a given baby’s development are. One mother who resisted pressure to give up her baby[2] said that her doctor incorrectly told her the child would not survive three months or grow teeth. That child is now three years old, with a mouth full of teeth. In another case reported by Human Rights Watch in 2017 (Human Rights Watch, 2017), a male respondent aged 46 said that he gave up his daughter with cerebral palsy to an orphanage because doctors had given him false information about the adverse influence a child with a disability might have on other children. “The neurologist said that we should send her away and have another child.” (Human Rights Watch, 2017) In another case also reported by Human Rights Watch, parents of a baby with Down syndrome were told by their long-time family doctor that their baby would only survive a few days. The doctor explained the option of giving up the child and, without any other information, the parents complied and signed the papers to institutionalize the baby. Five years later, they found their daughter in an orphanage and eventually brought her home. They said, “If we had known she would live, we wouldn’t have abandoned her!” (Human Rights Watch, 2017). Thus, there is a clear problem with the knowledge and training of the healthcare professionals themselves that prevents parents from getting an adequate, unbiased diagnosis, as well as prospects for improvement and information on any state or community support that should be accessible for parents to make a more informed decision.

1.2.4. Social Pressure on Mothers

In Armenia, the social pressure on the mother to give up the baby often begins at the maternity ward among the hospital staff and is the main prompt for enacting abandonment. Hospital staff, including doctors and nurses, believe they are helping the family when they persuade parents that the child will only have problems, will not improve and will be very difficult to take care of. UNICEF research found this practice to be common across Central East Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States (UNICEF, 2013). Hospital staff’s urging to reject the child, even when the mother wants to keep the baby, can also influence immediate family members, especially husbands and other household members, who often simply force the mother to give up the child.

Even without this persuasion from healthcare professionals and family, negative public attitudes of neighbors, friends and society as a whole towards disability can lead the mother to abandon her baby. This is the culmination of social values and individual beliefs, social stigma and the lack of public information about disabilities. With no other information about babies with disabilities, parents often feel they have no other option but to give up their child.

1.3. Steps Armenia has taken or is taking to address problems around disability

Armenia has adopted legislation and signed on to international agreements for the protection of people with disabilities. Armenia, for example, acknowledges the importance of family care for children in Article 13 of the Law on the Rights of the Child. Still, there are gaps in legislation that leave babies with disabilities vulnerable to abandonment.

The Armenian government is currently undertaking important reforms around disability, including reducing the number of children in state-run residential institutions and moving some children back to their families. However, the Armenian government seems to be prioritising the return of children without disabilities to their families (Human Rights Watch, 2017). Thus, although the total number of children in orphanages is decreasing, the concentration of those with disabilities in orphanages is increasing. Moreover, the government has announced its plans to transform three generalized orphanages for children without disabilities into community-based support centers, but it has made no commitments to transform or close the three orphanages where children with disabilities reside, continuing to invest in those institutions. This approach exacerbates the overrepresentation of children with disabilities in institutional care in Armenia and is discriminatory.

Children with disabilities in Armenia are entitled by law[3] to various forms of assistance from the state in the form of allowances, free or discounted benefits that cover healthcare, educational services, rehabilitation, sanatorium treatment and prescription medication.[4] Mothers of children with disabilities are entitled to childcare and disability benefits for one year after childbirth. People with disabilities are guaranteed free of charge or privileged aid at state medical institutions, funded by the state budget until the age of 18. Various forms of education and vocational training are also made available for persons with disabilities. The problem, however, is that these services are not geographically distributed. Many families, especially those outside Yerevan, still cannot afford the travel and extra expenses involved in caring for a child with disabilities. Also, these allowances do not address the countless hours of unpaid care and lost employment opportunities of the parents.

The Government of Armenia is also taking important steps to help children with disabilities be a part of their community. In 2005, the Armenian government adopted the Law on Education on Persons with Special Educational Needs, which introduced inclusive education[5] in Armenia. In 2014, it amended the Law on Special Education to establish universal inclusive education as a state policy in Armenia (Beglaryan, 2013). According to the Ministry of Education, in 2015, there were around 190 inclusive schools in Armenia, which were attended by around 5,000 children with special needs. Of those, 2,200 went to special education schools while 3,000 went to inclusive schools. Despite some progress, children with disabilities continue to face segregation and stigma and do not always receive the reasonable accommodation in schools that would enable them to study on an equal basis with other children. Moreover, many of these inclusive schools limit their “inclusiveness” to ramps that allow access for those children with wheelchairs (Partnership for Open Society Initiative, 2012). Inclusive schools must be inclusive in a more holistic way and must be able to provide more individualised care. The educators’ professional expertise, knowledge, skills, attitudes and commitment to the mission are of utmost importance.

1.3.1. Perinatal Care

In Armenia, women of reproductive age are entitled by law to free medical care and services for the duration of their pregnancy, childbirth, and a postpartum period of 42 days.[6] Additionally, the Ministry of Health approved, by government decree[7], state-guaranteed free medical care and OB-GYN outpatient services, organized by region.[8] Armenian law provides for free referrals of women by their OB-GYN to medical specialists of any specialization, facility and laboratory for diagnostic examinations; prescriptions are also provided for. The same decree[9] also provides for physical and psychosocial preparation of pregnant women, which starts from the very first visit of the pregnant woman to a doctor and finishes at the end of the pregnancy with 5-6 visits overall.

The Armenian state also provides for free maternity classes for new mothers, which are intended to teach basic information about childbirth, the postpartum period and childcare overall. The problem is that attendance is not obligatory and that few parents express the desire to attend these classes. Even if these classes were attended, they do not provide unbiased, non-stigmatizing information or resources about the possibility of disability. They also do not include psychosocial support for women whose unborn baby has already been diagnosed with a disability.

Thus, Armenian legislation clearly provides state support for families of children with disabilities as well as for pregnancy. However, there are some problems and gaps therein. Women often do not use the check-ups offered before birth, not all disabilities can be detected and there is not adequate information on disabilities offered from healthcare professionals.

1.4. Problems

Based on an assessment of the main reasons for giving up babies with disabilities as well as the gaps in existing Armenian legislation which relates to children with a disability, the following problems have been identified:

- Social stigmatization around disability in Armenia leads to widespread beliefs that people with disabilities can never be integrated into society or live full lives.

- Doctors, nurses and other healthcare workers impose their own social biases around disability and pressure the parents to give up the baby at a time when the mother is at her most vulnerable, post-birth.

- Doctors, nurses and social workers give stigmatizing, incorrect or incomplete information about a child’s disability and their prospects for life to parents. These professionals who, according to Armenian law[10], must talk to the parents who want to give up the child often lack the appropriate vocational education and often add to the social pressure to give up the baby.

- Many women do not utilize the free medical care and services provided and can miss potential diagnoses of disability that could give them the chance to gain more information to prepare them for a positive outcome. Indeed, many women only refer to their doctor at childbirth.

- Financial and social support available for families with children with disabilities is not adequate for families outside Yerevan.

- Armenian law does not provide any specialized mechanisms of support for pregnant women whose fetuses have been found to have a disability. While Chapters 11, 12, and 13 of the N 77-N 12 March 2014 decree provide for psychosocial support to prepare women for childbirth, there is no psychological or informational support for women whose fetus has a disability.

Thus, although the legislative framework for protecting children with disabilities exists and is compliant with international norms, and despite the fact that a number of steps have been taken in recent years to reform the relevant sectors in Armenia, there are still gaps in legislative acts and legal documents that must be addressed.

2. Policy options

There are many policy options to prevent the institutionalization of babies with disabilities. In international contexts, changing public attitudes toward disability is a major component of addressing more specific issues. UNICEF evidence suggests that CEE and CIS countries have a long way to go in changing traditional attitudes that are built into the physical and social environments – from accessible buildings and public transportation to integrated classrooms and informed public opinion. This sort of broad remedy, as important as it is to address eventually, falls outside the scope of this white paper. The following policy options, however, address aspects of the specific problem of the institutionalization of babies with disabilities in Armenia more directly. Each policy option is presented followed by a list of the main advantages and disadvantages as they pertain to the current policy problem.

2.1. Cash Transfer

Addressing the financial difficulty of raising a child with disabilities, Armenia can provide support through social protection initiatives such as cash transfer programs. This intervention can also tackle the increased risk of poverty among families with children with disabilities. Countries in transition, including Moldova, Serbia, several countries in South America and South Africa provide some cash benefit for otherwise unpaid caregivers in families with people with disabilities.

A growing number of low- and middle-income countries are building on promising results from these broader efforts and have launched targeted social protection initiatives that include cash transfers specifically for children with disabilities. These countries include Bangladesh, Brazil, Chile, India, Lesotho, Mozambique, Namibia, Nepal, South Africa, Turkey and Vietnam. The type of allowances and criteria for receiving them may vary greatly. Some are tied to the severity of the child’s impairment. Routine monitoring and evaluation of the transfers’ effects on the health, educational and recreational attainment of children with disabilities are essential to making sure these transfers achieve their objectives.

Advantages:

- Shown to benefit children.

- Relatively easy to administer and provide for flexibility in meeting the particular needs of parents and children.

- Respects the decision-making rights of parents and children.

Disadvantages:

- Can be difficult to gauge the extent to which they are used by and useful to children with disabilities and those who care for them.

- Does not address the social stigma encountered from hospital staff or communities.

- Not appropriate when the supply of essential goods is disrupted (e.g. war).

- Not appropriate in shallow financial markets like Armenia’s where it is difficult to move cash.

2.2. Disability-specific Budgeting

Another tool Armenia can use to address the financial aspect is disability-specific budgeting. For instance, a government that has committed to ensuring that all children receive free, high-quality education would include specific goals regarding children with disabilities from the outset and take care to allocate a sufficient portion of available resources to covering such needs as training teachers, making infrastructure and curricula accessible and procuring and fitting assistive devices.

Disability-specific budgeting could, for example, cover assistive technology to provide any necessary assistive devices and services to the child, including for mobility (e.g. walking stick, prosthetics, toilet seats), vision (e.g. eyeglasses, magnifying software, Braille systems for reading and writing, screen reader for computer), hearing (e.g. headphones, hearing aids, amplified telephone), communication (e.g. communication card with texts, communication board with letters, symbols or pictures, electronic communication devices with recorded or synthetic speech) and cognition (task lists, picture-based instructions, manual or automatic reminder, adapted toys or games).

Effective access to services including education, habilitation (training and treatment to carry out the activities of daily living), rehabilitation (products and services to help restore function after an impairment) and recreation should be provided free of charge and be consistent with promoting the fullest possible social integration and individual development of the child, including cultural and spiritual development. Such measures can promote inclusion in society, in the spirit of Article 23 of the UN’s Convention on the Rights of Children (CRC), which states that a child with a disability “should enjoy a full and decent life, in conditions which ensure dignity, promote self-reliance and facilitate the child’s active participation in the community.”

Advantages:

- Can cover much of the direct costs taken on by families of children with disabilities for necessary things that are not covered in current legislation.

- Can address some of the shortcomings associated with current efforts at implementing inclusive schools.

Disadvantages:

- Does not address the lack of information and treatment by hospital staff.

- Does not address social stigma.

- Does not (immediately) address accessibility/financial needs for those who live outside Yerevan.

2.3. Retraining Healthcare Staff

Training and retraining of healthcare professionals targets the potential perpetrators of stigma in the hospital setting, when and where the decision to abandon a baby is made. Such training can also increase the knowledge of healthcare workers about disability. It can eradicate social stigma among hospital staff, can increase the quality of diagnoses and give parents hope for their child. This approach also aligns with the human-rights based understanding of disability by raising awareness of the dignity and needs of persons with disabilities through training and the promulgation of ethical standards for public and private health care.

Advantages:

- Addresses the most immediate cause of the problem.

- Can improve overall professionalism of healthcare staff, combats stigmatizing attitudes of healthcare professionals and sensitizes them to disability issues overall.

- Can be easily monitored and measured.

- Serves to combat stigmatizing attitudes toward disability among parents as they will understand the issue in a compassionate, unbiased manner from an authority figure.

Disadvantages:

- Does not address the material needs of parents.

- Does not provide social or community support.

3. Recommendations

Based on the fact that the majority of the cases of abandonment of children with disabilities occur in the hospital setting at the behest of healthcare staff, the most suitable policy intervention would be to retrain healthcare professionals about disability and how to communicate news of disability to a mother who has just given birth. This intervention was chosen for its focus on improving the knowledge of professionals and parents, as they are the ones directly involved in the decision to abandon children with disabilities. This policy intervention was chosen also for its alignment with existing Armenian legal commitments to keeping children with their families, as well as the internationally accepted social and human rights model of disability. Moreover, unlike the other policy options, this intervention is actionable and does not require any additional processes for implementation.

There are two parts to this recommendation:

1. Retraining healthcare professionals on communicating the news of disability to parents, whether prenatally or postnatally, including giving parents up-to-date information about the given baby’s specific disability;

2. Retraining healthcare professionals and social workers about disability as a whole, including the negative impact of social stigmatization.

3.1. Retraining Healthcare Professionals on Communicating the News of Disability to Parents

Discussions between parents and healthcare providers – both at the prenatal as well as postnatal periods must be based on compassionate, supportive communication that forms the basis of this intervention. To ensure a positive outcome for the mother and to promote optimal baby bonding, it is important for the doctor to support and communicate with parents throughout the time it takes to process and accept the news of a baby’s disability. It is also important to share information on the sensitive topic of baby disability with other expectant couples in motherhood education classes.

A mother who experiences the news of a baby’s disability needs a healthcare professional who will recognize the pain and feelings of loss associated with the diagnosis and who will tell her it is acceptable to express her feelings. At some point, there is also a need for hope – hope that the parents and family will adapt; hope that the family will continue to function in a positive manner; and hope that the child will participate in many “normal” childhood activities. Due to the overwhelming initial sense of loss, such future accomplishments may seem inconceivable; however, they are usually attainable.

With prenatal or postnatal diagnosis, it is emphasized that the joy of the birth should not be diminished. Unfortunately, when diagnosis of a baby’s disability is suspected or confirmed, most health-care providers are uncomfortable and ill-prepared to talk to parents and tend to liken it to a tragedy. It is not uncommon for physicians to delay informing the parents of a confirmed diagnosis, and few birthing centres have an established protocol for relaying such information. In order to address this issue, the following steps must be taken:

3.1.1. Ensuring a Private Setting

The healthcare professional giving the news must foster a positive attitude and give parents hope. It is important to have both parents present, if possible, and to provide a private area for this discussion, with uninterrupted time for them to ask questions and express their feelings. The physician or perinatal educator can clearly explain how the diagnosis was established and present objective clinical data. It is also helpful if parents are informed together in a compassionate and caring manner. The healthcare professional might offer to stay as long as possible to answer further questions. Similarly, if the parents prefer to return at a later time to further discuss the diagnosis, another meeting may be scheduled.

The physician and perinatal nurse educator might also consider limiting the number of healthcare personnel, such as support staff, present during the discussion. For parents, it can be an emotionally-charged and seemingly unbearable moment, and it is not the appropriate time to have several medical staff in the room. It is advised that this decision be made by the healthcare professionals, with the parents’ permission.

3.1.2. Timing

The timing of relaying a postnatal diagnosis is critical. In a retrospective survey of 1,250 mothers who gave birth to a child with Down syndrome, Skotko (2005) found that mothers who learned of the diagnosis after birth felt they would have preferred being informed earlier, as soon as the diagnosis was confirmed. Respondents who reported a delay of more than 24 hours from diagnosis to disclosure stated that they had noticed the healthcare team avoiding them or not making eye contact. These mothers, therefore, sensed that bad news was imminent. One participant reported that her obstetrician later told her he did not tell her the diagnosis because it was not his policy to give this type of information but, rather, that it was the pediatrician’s responsibility. This mother stated, “I felt I was the last to know” (Skotko, 2005, p. 70).

3.1.3. The Right Words

Wright (2002) discourages the use of the term “disabled baby,” which unconsciously emphasizes the disability first and the baby, or person, second. Instead, it is advisable to use the phrase “baby with a disability” or, better still, to refer to the baby by his or her name. If the child is unborn or unnamed, say “baby” in discussions.

The healthcare professional will be a supportive presence for parents. There are no right or wrong responses for family members at the time of diagnosis (Shepard and Mahon, 2000). The parents are experiencing a life-altering event and will be acquiring new roles. For many mothers, having a child with a disability often means resigning from a job or career. In Wright’s (2002) study, 9 out of 12 mothers were unable to continue their careers, thus creating a professional void and new financial concerns. Shepard and Mahon (2000) recommend the following three interventions when the diagnosis is revealed:

1. Be concrete. Give the family as much information as is immediately necessary, but do not overwhelm them.

2. Provide resources to the parents, as well as to the primary care provider and other members of the healthcare team, if they do not possess them. Advise the family about what comes next.

3. Help the family put the diagnosis and treatment plan in perspective. This guidance can be accomplished by ascertaining what expectations the family has and by clarifying any misconceptions.

3.1.4. Provide Current Information and Written Material

As the diagnosis is confirmed and disclosed, parents will need timely written and verbal information (Prezant and Marshak, 2006; Rahi, Manaras, Tuomainen, & Hundt, 2004; Skotko, 2005; Wright, 2002). The information can incorporate the disability, medical treatments, and available support groups and must be up-to-date and positive in tone. As reported by mothers in Wright’s (2002) research, nothing was more distressing than outdated information, which often insensitively portrayed an antiquated or stereotypical image of the baby or child with a disability. Printed materials are effective when they are objective and encouraging, presenting all aspects of the diagnosis. Mothers in Wright’s (2002) study also found it very disturbing when statistics were inaccurate or when members of the healthcare team prematurely predicted their child’s future cognitive and physical abilities.

For this reason, it is necessary to translate some of the best of these international resources into Armenian, tailoring for local cultural and social norms, and making them available to parents at the hospital.

Reading materials are offered to parents with children with disabilities in the United States. Many of the most current resources can be found on the Internet, although they are predominantly in the English language. Well regarded resources are:

https://www.thearic.org

Breakthrough Parenting for Children with Special Needs: Raising the Bar of Expectations, by Judi Winter.

Raising a Handicapped Child, by Charlotte Thompson.

Special Children, Challenged Parents, by Robert A. Naseef (offers information and strategies for the mother and family).

3.1.5. Future Pregnancies

It is suggested that discussion of future pregnancies and genetic testing be objective, empathetic and carefully approached. Parents need to know their options, and mothers will feel comfortable talking about any concerns for future pregnancies if the healthcare professionals

are supportive and non-judgmental. In parent discussions, the healthcare team can avoid talking about the disability as if it were a disaster or “heartbreak.” In Wright’s (2002) study, the mother of a child with Down syndrome reported that her obstetrician advised an amniocentesis (sampling amniotic fluid for chromosomal abnormality) in any subsequent pregnancies. He told her, “Another child with a disability would be a heartache, and there is no reason in this world why you should have a child with a disability when testing and termination are options for you.” Although prenatal testing is advisable, the clinician should not pass judgment or personal opinions if the parent declines it.

3.2. Retraining Healthcare Professionals About Disability Generally

In order to make communicating the news of a disability of a baby truly effective, healthcare professionals must be aware of disability issues generally, including the impact that social stigma has on their patients who may have disabilities. This will serve to improve the quality of healthcare overall and will ultimately tackle the problem of stigma in health facilities in Armenia, which is a main root of the current policy problem. Healthcare workers, regardless of setting and service, should be provided with relevant professional training, which takes into account the principles of the CRPD and preferably involves people with disabilities as trainers to sensitize and familiarize service providers with their future clients.

This segment of the retraining intervention must begin with the provision of information to healthcare professionals, consisting of teaching about the various disabilities that they may encounter, as well as about stigma and its manifestations.

Further, there must be skill-building activities in creating opportunities for healthcare providers to develop the appropriate skills to work directly with patients with disabilities, including newborns and their parents. These activities can include discussion-based educational programs, interactive group work, role-playing, games, assignments and guided or controlled clinical practice.

This intervention must be carried out through contact with the stigmatized group. Indeed, members of the stigmatized group itself – people with disabilities – should be heavily relied on to deliver the training in order to develop empathy among the healthcare workers, to humanize the stigmatized individual and break down stereotypes. People with disabilities who may conduct training can also be supported by other professionals (e.g. professors, expert medical providers, external facilitators trained in stigma reduction). Contact with the stigmatized group can also be done through videos, in non-clinical interactions.

Structural approaches should be included to change hospital policies, provide clinical materials, redress systems and restructure facilities if necessary.

3.3. Steps Forward

The policy intervention, consisting of these two steps: retraining healthcare professionals to communicate the disability of a baby to parents and retraining healthcare professionals about disabilities generally can take place on two parallel fronts. Disability-sensitive curricula can be introduced at medical schools, making this training a regular part of undergraduate and postgraduate medical education in Armenia. Simultaneously, healthcare professionals who are already practicing can undergo retraining on disabilities.

3.3.1. Getting Started

It is important to ensure that resources are available and that the relevant partners and stakeholders are ready to develop and implement the program. It is neither expected nor possible for the ministry, department, local authority or organization that initiates a retraining program to implement every component of it. It is essential that they develop partnerships with the different stakeholders responsible for each component and develop a comprehensive program. Each sector should be encouraged to take responsibility for ensuring that its programs and services are inclusive and respond to the needs of persons with disabilities, their families and communities. For example, it is suggested that the Ministry of Health and nongovernmental organizations working in the health sector take responsibility for the health component, the Ministry of Education and non-governmental organizations working in the education sector take responsibility for the education component and so on.

3.3.2. Geographical Coverage

A retraining program in Armenia can be local, regional or national. The type of coverage will depend on who is implementing the program, what the areas of intervention are, and the resources available. It is important to remember that support is needed for people with disabilities and their families as close as possible to their own communities, especially rural areas. Resources are limited in most low-income countries and are concentrated in the capital or big cities. The challenge for planners is to find the most appropriate solution to achieve an optimum quality of services in regional medical centers, given the realities of the needs and existing resources in the local situation.

3.3.3. Management Structure for Retraining

Retraining may be organized by regional territory in Armenia, as it is not possible to provide one overall management structure for the whole country. Committees may be established to assist with the management of the program, and they are encouraged. Retraining committees are usually made up of people with disabilities, their family members, interested members of the community and representatives of government authorities. They are useful for:

- Setting the mission and vision of the retraining program;

- Identifying needs and available local resources;

- Defining the roles and responsibilities of personnel and stakeholders;

- Developing a plan of action;

- Mobilizing resources for program implementation;

- Providing support and guidance for program managers.

3.3.4. Participatory Management

In most situations, program managers will be responsible for making the final decisions; however, it is important that all key stakeholders, particularly people with disabilities and their family members, are actively involved at all stages of the management and decision-making cycle. Stakeholders can provide valuable input by sharing their experiences, observations and recommendations. Their participation throughout the management cycle will help ensure that the program responds to the needs of the community and that the community helps to sustain the program in the long term.

3.3.5. Sustaining Retraining Programs

While good intentions help to start such retraining programs, they are never enough to run and sustain them. Overall, experience shows that, compared with civil society programs, government-led programs or government-supported programs provide more resources and have a larger reach and better sustainability. However, programs led by civil society usually make retraining work in difficult situations and ensure better community participation and sense of ownership. Retraining will be most successful where there is government support and where it is sensitive to local factors, such as finances, human resources and support from stakeholders, including local authorities and disability organizations.

Some essential ingredients for sustainability which retraining programs should consider are listed below:

- Effective leadership – it would be very difficult to sustain a retraining program without effective leadership and management. Program managers are responsible for motivating, inspiring, directing and supporting stakeholders to achieve program goals and outcomes. Thus, it is important to select strong leaders who are committed, excellent communicators and respected by stakeholder groups and the wider community.

- Partnerships – if they work separately, retraining programs are at risk of competing with others in the community, duplicating services and wasting valuable resources. Partnerships can help to make the best use of existing resources and sustain programs by providing mainstreaming opportunities, a greater range of knowledge and skills, financial resources and an additional voice to influence government legislation and policy relating to the rights of persons with disabilities. In many situations, formal arrangements, such as service agreements, memoranda of understanding and contracts, can help secure and sustain partners’ involvement.

- Building capacity – building the capacity of stakeholders to plan, implement, monitor and evaluate programs will contribute to sustainability. Programs should have a strong awareness-raising and training component to help build capacity among stakeholders. For example, building capacity among people with disabilities will ensure that they have the relevant skills to advocate for their inclusion in mainstream initiatives.

- Financial support – it is important that all programs develop stable funding sources. A range of different funding options may be available, including government funding (e.g. direct financing or grants), donor funding (e.g. submitting project proposals to national or international donors for funding, in-kind donations or sponsorship), and self-generated income (e.g. selling products, fees and charges for services, or microfinance).

- Political support – a national policy, a national program, a network and the necessary budgetary support will ensure that the training is carried out according to the principles outlined in CRPD.

3.3.6. Training Medical Students

The retraining program of practicing medical professionals could feasibly be limited to five years, while simultaneously introducing the curriculum to medical students in higher education for the longer term. While continued training of practicing healthcare professionals is always necessary, the focus of training can, if successful, eventually move to medical and social work students – Armenia’s future doctors, nurses and social workers. The World Health Organisation (WHO) makes the following recommendations (see World Health Organisation, 2011):

- Healthcare workers should be taught the causes, consequences and treatment of disabling conditions and about the incorrect assumptions about disabilities that result from stigmatized views about people with disabilities.

– A survey of general practitioners in France recommends the introduction of disability courses into medical school curricula and in continuing education. In one approach, people with disabilities educate students and healthcare providers on a wide range of issues, including discriminatory attitudes and practices, communication skills, physical accessibility, the need for preventive care and the consequences of poor care coordination.

- Disability education should be integrated into undergraduate training for healthcare professionals.

– In a United States study, third-year medical students reported that they felt less “awkward” and “sorry for” people with disabilities after attending a 90-minute education session.

– A study of fourth-year medical students used panel presentations led by individuals with disabilities. Students reported that they valued hearing about the personal experiences of people with disabilities and about what worked and what did not in the medical setting and in patient-provider relationships.

Moreover, such education should be implemented according to the social and human rights perspective in a way that complements, not negates, the medical one. Healthcare professionals must understand that the issue of disability far transcends the medical context. Rather, they must be trained to understand disability as a multilevel set of issues – often social, often cultural – that affect their patients in ways that are just as, if not more, debilitating than the medical or physical issue itself.

3.3.7. The Management Cycle

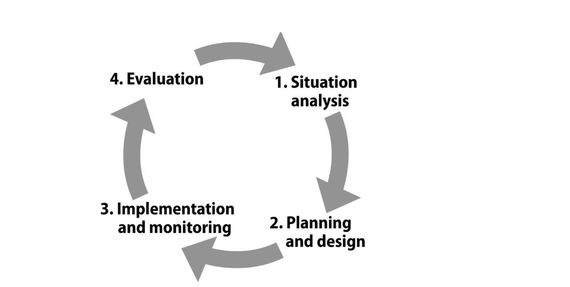

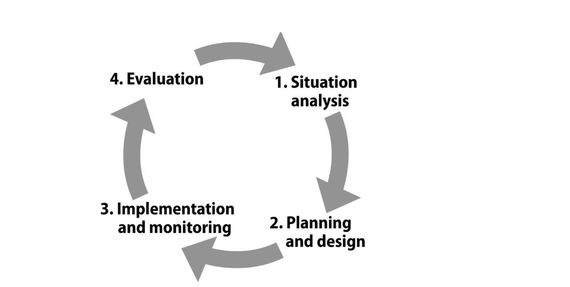

When thinking about developing or strengthening a retraining program, it is helpful to visualize the whole management process as a cycle (see Fig. 1). Doing so ensures that all the main parts are considered and shows how they all fit and link with one another. In these guidelines, the management cycle consists of the following four stages:

The Management Cycle.

1. Situation analysis – this stage looks at the current situation in the community for people with disabilities and their families and identifies the problems and issues that need to be addressed.

2. Planning and design – the next stage involves deciding what the CBR program should do to address these problems and issues and planning how to do it.

3. Implementation and monitoring – at this stage, the program is carried out with regular monitoring and review to ensure it is on the right track.

4. Evaluation – this stage measures the program against its outcomes to see whether and how the outcomes have been met and assess the overall impact of the program, e.g. what changes have occurred as a result of the program.

4. Conclusion

The problem of disability in Armenia is complex and multi-layered This white paper addresses only one aspect of the problem – the rejection of babies born with disabilities and their often life-long institutionalization. The roots of this specific problem are social stigma, lack of financial resources to care for a child with a disability and a lack of information available to parents about disability generally and the disability of their child specifically. The potential policy interventions are many, but the policy intervention of retraining was chosen for its simplicity and its potential to tackle two key aspects of the problem at once: (1) social stigma – and specifically that of key stakeholders – primary healthcare providers and parents; and (2) the lack of sufficient, unbiased information available to families about disability generally, including the services that are in place to support them.

Special thanks to Ani Avetisyan and Susanna Gevorgyan for assisting the research.

1- A 2001 study in the UK found that parents of children with disabilities spend almost twice as much on comparable items as parents of able-bodied children (Dobson, Middleton, & Beardsworth, 2001), highlighting the need for adequate support for the family.

2- This mother received assistance from the Bari Mama NGO.

3- For example, Article 11 of the RA Law on the Social Protection of Persons with Disabilities; The Law on State Benefits of 12 December and Paragraph 1 of Article 30.

4- Children with disabilities of 1st and 2nd groups are entitled to free prescription medication, and children with disabilities of the 3rd group are entitled to a 50% discount on medication if they do not have the right to receive more.

5- Inclusive education is education for all regardless of the physical, social or mental impairments and ensures equal treatment of everyone.

6- Subparagraph 6 of Appendix 1, Decision N 318-N of 4 March 2004

7- Subparagraph 1 of Clause 1 of Decree N 77-N of 12 March 2014

8- Decree N 77-N of 12 March 2014

9- Paragraph 11 of Decree N 77-N of 12 March 2014

10- HO-231-N Law on Social Assistance of December 17, 2014 (2014 թվականի դեկտեմբերի 17-ի «Սոցիալական աջակցության մասին» ՀՕ-231-Ն օրենք

References

Bayrakdarian, K. A. (2018, March 13). A Hidden Minority: Children With Disabilities in Armenia. EVN Report.

Beglaryan, A. (2013, June 10). Հայաստանում ներդրվում է ներառական կրթության համակարգը. Hetq.

Christian Blind Mission. (2015). Disability Inclusive Development Tioolkit. Bensheim: Christian Blind Mission.

Council of Europe. (2018). Upholding the human rights of persons with disabilities in Armenia. Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

Dobson, B., Middleton, S., & Beardsworth, A. (2001). The impact of childhood disability on family life. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Ejiri, K., & Matsuzawa, A. (2017). Factors associated with employment of mothers caring for children with intellectual disabilities. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 1-9.

Faith to Action Initiative. (2014). Children, Orphanages, and Families: A Summary of Research to Help Guide Faith-Based Action. Faith to Action Initiative.

Government of the Republic of Armenia. (2011, July 7). Retrieved from Irtek: http://www.irtek.am/views/act.aspx?aid=61593

Gziryan, A. (2019, May 3). Կանխել երեխաների մուտքը մանկատներ. նախարար Բաթոյանը մանրամասներ է ներկայացնում նոր ծրագրերի վերաբերյալ. Retrieved from Armenpress: https://armenpress.am/arm/news/973456.html?fbclid=IwAR10ex4uN5A6Qdhlm17lYA_d5_EfPzSBNEw5HgEVZ7FkqDFoBCtgzKEcau8

Hanvey, L. (2002). Children with Disabilities and Their Families in Canada. Ottawa: National Children’s Alliance for the First National Roundtable on Children with Disabilities.

Human Rights Defender of the Republic of Armenia. (n.d.). Persons with Disabilities. Retrieved from Human Rights Defender of the Republic of Armenia: http://www.ombuds.am/en/categories/persons-with-disabilities.html

Human Rights Watch. (2017). Human Rights Watch Submission on Armenia to the Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. New York City: Human Rights Watch.

Human Rights Watch. (2017). “When Will I Get to Go Home?” Abuses and Discrimination against Children in Institutions and Lack of Access to Quality Inclusive Education in Armenia. New York City: Human Rights Watch.

Human Rights Watch. (2018). Armenia World Report. New York City: Human Rights Watch.

Mutler, A., Wong, G., & Crary, D. (2017, December 19). Global effort to get kids out of orphanages gains momentum. Associated Press.

Parish, S. L., Rose, R. A., Grinstein-Weiss, M., Richman, E. L., & Andrews, M. E. (2008). Material Hardship in U.S. Families Raising Children With Disabilities. Council for Exceptional Children, 71-92.

Partnership for Open Society Initiative. (2012). Submission to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child . Yerevan: Partnership for Open Society Initiative.

Roehr Institute. (2000). Finding a Way In: Parents on social assistance caring for children with disabilities . North York: Roehr Institute.

Rosenberg, T. (2018, October 16). The Lasting Pain of Children Sent to Orphanages, Rather Than Families. The New York Times.

Shakespeare, T. (2006). Disability Rights and Wrongs. London: Routledge.

UNICEF. (1998). Children and drug abuse. Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org/publications/files/Implementation_Handbook_for_the_Convention_on_the_Rights_of_the_Child_Part_3_of_3.pdf

UNICEF. (2013). Text-OnlyHigh ContrastAccessibility The State of the World’s Children: Children with Disabilities. New York City: UNICEF.

United Nations. (2006). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. New York City: United Nations.

United Nations. (2006). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and Optional Protocol. New York City: United Nations.

United Nations. (2008). UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/disabilities/default.asp?id=259

Williamson, J. (2014). A Family is for a Lifetime. Washington DC: The Synergy Project.

Williamson, J., & Greenberg, A. (2010). Families, Not Orphanages. Better Care Network. New York City: Better Care Network.

World Health Organization. (2011). World Report on Disability. New York City: World Health Organization.

Wright, J. T. (2002). Transcendence: Phenomenological perspective of the mother’s experience of having a child with a disability. Widener University.

This project is funded by the UK Government’s Conflict, Stability and Security Fund.

The opinions expressed are those of the authors’ and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the UK Government.