Կարդալ հայերեն

Կամավորությունը Հայաստանում. կամավորությանն առնչվող հիմնախնդիրներ

The Significance of Volunteering

Volunteering is an activity undertaken by an individual of their own free will for the general public good without financial consideration. It is often seen as a method to gain experience or learn new skills but its importance goes much beyond supplementary training. Volunteering is a key building block in forming civil society and a tool for social integration that counterbalances inequality. Social inclusion is the degree to which individuals are considered full members of society and are accepted by their peers as such. The Council of Europe describes social cohesion as the capacity of a society to ensure the well-being of its members, minimize disparities and avoid marginalization. Within this context, the participation level of members of society becomes a way to measure social cohesion and volunteering becomes a tool for social inclusion.

Legal analysis and discussion have shown that the Republic of Armenia does not view volunteering within the context of social cohesion but focuses on the advantages to the volunteer. This approach is stipulated in provisions set out in current regulations and ignores the importance of volunteering within the context of social inclusion. However, the issue does not end there. Currently, there is no unified, comprehensive regulation that establishes common norms for volunteering. Instead, laws and legislative acts have been established to regulate issues arising only in separate fields. On a legislative level, there are no regulations that aim at fostering and developing a culture of volunteerism. This policy analysis aims to explore the main motives for volunteering, how volunteer work is regulated and identify the key challenges surrounding volunteering in Armenia.

Based on behavioral and legislative analyses, as well as focus group discussions, the following key issues were identified with regard to volunteering in Armenia.

- Regulation pertaining to volunteering activities in Armenia has not been unified into a comprehensive framework. This type of activity is regulated through different laws and legislative acts, the aims of which are to solve individual issues separately. Moreover, there are discrepancies throughout these regulations.

- Current regulations do not include general definitions of the field’s key concepts.

- Current regulations protect neither the rights of the volunteer nor the host organization. They also fail to stipulate the responsibilities of the host organization.

- Existing regulations fail to fully define the different types of volunteering. There is no definition of volunteering provided in any current regulations. Meanwhile, a bill proposed in 2017 included only three types of volunteering: short-term, medium-term and long-term.

- Current regulations do not consider volunteering within the context of risk prevention, elimination of consequences and rapid response. Hence, there are no relevant legal foundations for fostering and developing volunteer activity.

- Existing regulations do not define the tools, rights and responsibilities of spontaneous volunteering during natural disasters and emergency situations as a type of volunteering.

- Both current existing regulations and proposed bills do not define the tools, rights and responsibilities of spontaneous volunteering during natural disasters and emergency situations as a type of volunteering.

- Existing regulations do not include mechanisms for fostering volunteering. This report’s International Experience section mentions that, for example, since 2014, the Czech Republic has been implementing a volunteering certification system, through which it is trying to support individuals in finding employment. Our country does not have similar mechanisms that would serve to foster and develop volunteering. Currently, EU volunteering organizations view volunteering as the most important link between receiving an education and entering the job market. The Republic of Armenia does not consider volunteering in this context. Meanwhile, international experience shows that volunteering can become a principal tool for reducing unemployment among youth.

- Existing regulations do not consider volunteering within the context of:

– reducing unemployment

– forming and developing civil society

– a tool for social inclusion

– creating economic and social values

– ensuring social equality

- Bills on the regulation of volunteering include clauses that can create over-regulation.

- Existing regulations do not include activities that foster cooperation between the public and private sectors within the field of volunteering.

- Existing regulations do not include provisions to foster the inclusion of people with disabilities in the volunteering field.

- There is a lack of focus on ensuring equal conditions for participating in volunteering activities in Armenia.

- Existing legislative provisions do not weigh in on the age of volunteers. In consequence, risks based on age are not eliminated or reduced.

- Existing regulations do not specifically clarify damage compensation mechanisms based on different types of volunteering.

- Existing regulations do not establish legal foundations for organizations to carry out volunteer work, nor do they outline their responsibilities and rights.

- Current regulations do not include tax policy mechanisms aimed at solving issues prevalent in the volunteering field and the development of that field.

- There is a need for programs that promote and raise awareness about volunteering due to a general lack of awareness.

- There are no opportunities for carrying out expert volunteer work, which would make it possible to recruit more volunteers.

- There is no unified database on volunteers which would, for example, serve as a foundation for developing fact-based policies on volunteering based on extensive statistical data.

- Since there is no relevant research on volunteering, motives aren’t taken into consideration when recruiting volunteers.

- Health and safety training is not provided when dangerous volunteer work is carried out.

- There are no established benefits or widespread social insurance mechanisms for volunteers, which would have promoted volunteer work.

1. Behavioral Research on Volunteering

1.1. Motives for Volunteering and Characteristics of Volunteers

Academic literature is filled with extensive research on volunteerism. The majority of these studies aim at shedding light on the motives for volunteering. Analyzing research on motives is necessary for developing successful policies. Specifically, by invoking the harmonization principle of demand and supply, the cornerstone of marketing, many theorists (Dolnicar and Randle, 2007) claim that, if a volunteer’s motives comply with a supply that suits that volunteer’s wishes, then the results will be mutually beneficial for all parties. These studies (Clary et al., 1998) once again show that if the volunteers’ demands are not met, they will stop working. Hence, understanding the motives of volunteers and drawing conclusions from them will help increase their number and also create other conditions to ensure they won’t quit prematurely.

There are two main theories predominant in modern studies on the motives of volunteering. A number of researchers claim that people volunteer for humanitarian reasons (Bussel and Forbes, 2002). The rest believe that the main reason for volunteering is for selfish reasons (Hibbert, Piacentini and Dajani, 2003). For example, volunteers can learn new skills that they can later use when entering the job market (Ziemek, 2006). It’s worth mentioning the fact that those countries that have high percentages of unemployment look at volunteering as an opportunity to gain working experience (Akintola, 2011). On the other hand, humanitarian and selfish motives can take place simultaneously (Wandersman and Alderman 1993; Rehberg, 2005). It’s true, volunteers usually specify several factors that have affected their decisions (Wandersman and Alderman, 1993; Rundle, 2007; Akintola, 2011). By combining the results of different surveys (Dolnicar and Randle, 2007; Akintola 2011; Carpenter and Myers 2010) the following motives to volunteer can be identified:

- Personal or family involvement

- Personal gratification

- Social contract

- Religious beliefs

- Being active

- Learning new skills

- Doing work for the good of society

- Helping others

- Gaining experience

- Using skills and knowledge

- Sense of responsibility

- Making friends

- Simple coincidence

Theorists have classified volunteers by type into six segments by combining grouped motives with age and gender demographics (Dolnicar and Randle, 2007). They are:

- Classic volunteers

- Devoted volunteers

- Involved volunteers

- Volunteers pursuing personal gratification

- Humanitarian volunteers

- Gainful volunteers

The main aim of classic volunteers is to carry out valuable work beneficial for society. They are usually older, not active in the labor market and are involved in volunteer work with great enthusiasm. Devoted volunteers spend a lot of time volunteering and collaborate with many volunteer organizations. They list several motivations to volunteer that are equally important. Involved volunteers spend limited time volunteering at institutions in which they have relatives or acquaintances. Volunteers pursuing personal gratification seldom claim to help others as their main motivation. Instead, humanitarian volunteers claim their cornerstone motivation to be helping those around them. Gainful volunteers stand out as highly educated, comparably young volunteers. They are new in the volunteering world. Their motivation comes from areas not specific to volunteers; they wish to gain experience in a given field or they ended up in the field by chance.

The relative size of these groups varies from country to country. In any case, the results of this analysis can be helpful in creating a new hypothesis or comparative studies. Hence, every country needs its own study.

1.2. Results and Analysis

1.2.1. Teenagers (Ages 14 – 20)

Motives

The reasons for volunteering in this age group are multifaceted. Their motivations can be divided based on stages: before volunteering and post-volunteering. Initially, romanticism and having an interesting time is what makes them want to volunteer. They also mention changing the world, being helpful, changing a boring daily routine, interacting with other people and doing interesting work as reasons to volunteer. Later on, volunteering is observed as a tool for self-awareness; volunteering work can be used to evaluate their own potential in different fields and to figure out what profession they would like to pursue. Volunteering is also viewed as an investment in the future. However, the prospects for their future are not yet clearly defined as volunteers at this age are still open to different potential fields and career paths. These volunteers state that volunteering does help them find work and gain professional promotions, even if that profession is yet to be determined.

They emphasize the importance of gaining life experiences which would help them become more self-confident, wise and conscious. Analysis of existing data shows that volunteers in this age group want to ensure their smooth transition into adulthood through work experience. The tendency of repetitive mentors is also eye-catching. This becomes evident later on when they seek to find organizational or non-ordinary work.

The Realization of Excelling Personally

A clear sense of excelling personally is quite visible in this volunteer age group. It is expressed through their job satisfaction, giving their contribution to important work and the feeling of serving the public interest compared to their peers. This group clearly distinguishes itself from self-oriented volunteers. Focus group participants stated that many of their peers volunteer just to have something “to show on paper.” Their main motives are personal gains and having a piece of paper proving they’ve volunteered for university applications or for receiving tuition fee assistance. However, having a selfish motivation is not to be criticized. It’s possible this “forceful volunteering” may lead to a desire to serve the public good in the future. In any case, according to the participants, self-oriented volunteers are indifferent to the work they do.

Present Issues

Even though volunteer work is described as a positive phenomenon, this age group singles out several issues that they have witnessed throughout their experiences. These issues include the possibility of finding yourself in conflict situations due to the work being done, being included in age-inappropriate conversations, encountering flaws in work-related coordination and possible public pressure. It’s noteworthy that compared to other age groups, this group doesn’t mention feeling unappreciated. This can be explained by the fact that the young age group has a light workload, is likely to volunteer in the summers only and is involved in relatively fun and easy work. Hence, they don’t expect encouragement, praise and appreciation.

1.2.2. Early Career (Ages 21 – 30)

Motives

Volunteers in this age group are mainly involved in professional fields. It helps them with job promotions. One of the motives they specify is the humanitarian factor. They are mentally satisfied by helping others and feeling appreciated. According to participants of this focus group, volunteer work (such as internships) in their own field helps them gain job experience and new skills. This, in turn, helps them become more organized and feel more confident. This age group does not hide the fact that an organization’s reputation is an important factor in their decision to spend time there. Volunteering in a well-known organization or company is attractive because you get to witness what goes on inside, exchange experiences, develop professionally, build a network and for other reasons as well. Nevertheless, to keep them engaged, it is important to comprehend the actual idea of volunteering which is their main driving force.

EVN Report’s the Reader’s Forum section is meant to create a space and platform for readers to be co-creators of engaged, credible journalism, to have a voice in driving policy development and to collaborate in bringing about a more informed public discourse. We want you, our reader, to be part of the conversation and that is why we are inviting you to read our White Papers, leave a comment, ask a question, make a recommendation and be part of the conversation.

Table of Contents

The Significance of Volunteering

1. BEHAVIORAL RESEARCH ON VOLUNTEERING

1.1. Motives for Volunteering and Characteristics of Volunteers

1.2. Results & Analysis

1.2.1. Young Age Group

1.2.2. Middle Age Group

1.2.3. Older Age Group

1.2.4. Group of Non-Volunteers

1.3. Integrating International Experience and Academic Literature with the Armenian Case

1.3.1. Altruism or Egoism?

1.3.2. Classifying Volunteers by Type

2. HOW VOLUNTEERING RELATIONS ARE REGULATED IN THE REPUBLIC OF ARMENIA

2.1. Legislative Acts and Laws

2.2. Proposed Bills on the Regulation of Volunteering Relations

2.3. The International Experience on How Volunteering Relations are Regulated

3. RECOMMENDATIONS

3.1. Recommendations on Field-Specific Policy Development

3.2. Recommendations on Field-Specific Legal Regulations

Reference List

Methodology

This policy analysis aims at identifying the main motives for volunteer work in the Republic of Armenia, with the aim of creating more favorable conditions for volunteer work. It also looks into legal regulations concerning volunteer work and dissects the results of meetings with experts, which identify several key issues.

The analysis targets two main questions:

What are the main motives for volunteering in Armenia?

How can volunteering be promoted in Armenia?

By identifying motives for volunteering, this analysis segments volunteers based on demographics and behavioral trends. The examination and analysis of these motives indicate the need for changes in legal regulations, which can create more favorable conditions for promoting volunteer work.

To answer the first question mentioned above, four focus group discussions were conducted. The first three targeted groups included participants from different age groups (younger than 20, 21-30, 31 and older). The reason for choosing these age ranges is to place a special emphasis on the 14-20 year olds, which make up the majority of volunteers in Armenia.. The number of mature adult volunteers in Armenia is quite low. Hence, the range for the oldest age group was set at 31 and above. The fourth focus group was conducted with participants who had never volunteered anywhere, in order to also get a sense of the motives that drove those who did not participate in volunteer activities. The questionnaires were developed based on research in academic literature and consultative interviews. The survey data was transcribed and thematically analyzed (see, Attride-Sterling 2001) in order to present the data more comprehensively. Then, the classification table of different types of volunteers was prepared.

To answer the second question, current legal regulations in the field were thoroughly analyzed. The results were compared to recommendations based on international experience. Consultative interviews with state body representatives also served as a foundation for the results.

The last section of this analysis presents recommendations for promoting volunteering in Armenia based on an analysis of the data collected. Specifically, the final section includes factors aimed at developing policies and necessary regulations.

Transitional Justice

Teaser

White Paper

Transitional Justice Agenda for the Republic of Armenia

Should Armenia implement the tools of transitional justice? This White Paper, developed by Dr. Nerses Kopalyan is a comprehensive transitional justice agenda for the Republic of Armenia.

Read moreFoster Care

Future Prospects for Foster Care for Children with Disabilities in Armenia

A child’s right to family life is enshrined in Armenian and international legal documents and considered a priority in Armenia’s 2017-2021 Strategic Plan on the Protection of the Rights of the Child. Here is EVN Report's White Paper about specialized foster care for children with disabilities.

Read moreThe Realization of Personal Excellence

A clear sense of personal excellence is visible in this volunteer age group as well. They understand that volunteering isn’t for everyone. Just like volunteers from the younger age group, volunteers from this intermediate age group also compare themselves to peers who don’t volunteer or are self-oriented volunteers. They also compare themselves to the younger cohort who volunteer mainly in the summer months for fun. Nevertheless, this type of involvement is still acceptable, as are self-oriented ambitions. Furthermore, the motives of mindful people may change during the course of volunteering.

Issues as Challenges

This volunteer age group accepts issues as challenges. If addressed properly, the issues they face can make them more skillful and experienced. Having a lot of experience volunteering, participants of this focus group also spoke about ways to get more volunteers involved in their field. They mainly discuss raising awareness in schools, which would allow children to understand the importance of volunteering. They consider a lack of awareness as a great obstacle. This can be solved through awareness campaigns. They also believe that mandating volunteering can be productive. This would be possible if universities and employers start considering volunteer work as a preferred and necessary precondition for acceptance. According to the focus group, these steps would help increase the number of volunteers.

1.2.3. Mature Adults (Ages 31 and older)

Motives

The main motivation for this group can be equally divided between humanitarian and more pragmatic factors, with work satisfaction as the main motive. Another motive, that is no less important, has several layers. These layers tend to include overcoming professional shortcomings, developing skills and knowledge, and maintaining capabilities. For example, volunteering in a foreign language environment helps maintain and develop that foreign language. Other age groups try to gain experience and skills through volunteering, while the oldest age group tries to maintain their knowledge and skills through volunteering. As a result, volunteering in a professional field is an important precondition for volunteering in this age group.

Feeling Unappreciated

Compared to the other age groups, this group has specific concerns regarding volunteering – mainly feeling unappreciated. What displeases them especially is that they are not encouraged by state bodies. Even though they claim that appreciation can be expressed through words of gratitude, they, however, would be happy if volunteers were encouraged even if symbolically and received financial incentives to feel more appreciated. This way they would be able to cover food and transportation costs as well. Numerous benefits and social insurance can also be a way of expressing appreciation.

Clear Solutions for Current Issues

These experienced volunteers suggest different solutions. According to them, the main issue is the absence of a volunteering culture. They mainly accredit this with what has been inherited from the Soviet years. The other issue they raise is the consequences of not having a law on volunteering. As a result, volunteers can be abused or not work in general (based on the principle of “I’ll do it if I feel like it”), cannot be protected (if they’re physically harmed), or volunteers without relevant qualifications or experience might harm themselves because of volunteer work.

Volunteering culture can be developed in children from a young age. They should be trained and taught about volunteer culture and encouraged to volunteer through interesting methods. All these issues can be solved through relevant laws that would regulate the field’s shortcomings and increase the number of volunteers.

1.2.4. Group of Non-Volunteers

Despite the fact that this group respects the idea of volunteering, they have never done volunteer work in their lives. Group members indicated the reasons they’ve never volunteered, criticized the phenomenon itself or tried to compare volunteering to other phenomena to show that they to have in some way or another volunteered as well.

The main reasons for not volunteering was time limitations, the lack of a supportive environment (never witnessed it at home, never did it in school), public opinion, e.g. negative perceptions of unpaid jobs, or the incompatibility of volunteer work with manhood/masculinity. One of the participants, for example, stated, “Several years ago, a lot of people signed up to volunteer and went to the border [with Azerbaijan], but many of them would never agree to pick up a shovel and work in a field.”

The participants all have their own interpretation of the ideal volunteer. Even a partial deviation from that image is seen as negative and is used as a justification as to why they’re not involved in volunteering. The ideal volunteer is selfless and does unpaid work in his/her professional field only. Anything outside this definition is considered as radical, political activism or self-interest. This group stated that, if they could do volunteer work in their own professional field, it’s possible that they would do it. However, they found it difficult to imagine how they could use their skills within the format of volunteering.

This group often draws parallels between volunteering and charity, kind work and selfless acts. However, they also raise the issue of whether the latter is volunteering or not. It’s possible that these comparisons are a result of misinformation because they often identified political and environmental activists as volunteers. It’s noteworthy that this group often gave alternative suggestions for volunteering. For example, making sure that relevant bodies carry out their work efficiently, eliminating the need for volunteer work.

1.3. Comparing International Experience and Academic Literature to the Armenian Example/Experience

1.3.1. Altruism or Egoism?

Data analysis shows that motives for volunteering include humanitarian and accountability factors. These are proportionally different in all age groups. It can be said that motivations for volunteering are driven by altruistic or egoistic factors only (Wandersman and Alderman 1993; Rehberg 2005). It’s noteworthy that conditions that motivate volunteer work include serious incentives mainly expressed through prospects of gaining experience, skills and knowledge. In certain cases, these are what determine the decision to do unpaid work. Nevertheless, the desire to carry out humanitarian work for the public good is the essential condition that ensures the continuation of being involved in volunteer work.

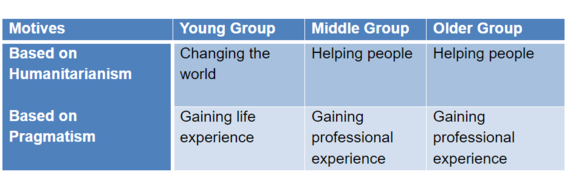

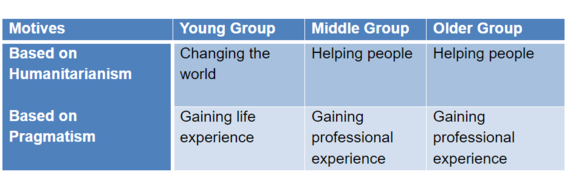

Humanitarian motives. Altruistic aspirations in the young age group are mostly expressed through the desire to change the world and do something positive. The other age groups consider the desire to help people as their main motivational factor.

Motives based on accountability. Factors for being interested in volunteer work are different in all age groups. Young volunteers want to gain as much life experience as possible and not professional experience because they may not have decided what profession they want to pursue yet. The middle and older age groups try to fill in the gaps they have in terms of professional skills and experience. It’s noteworthy that adults try harder to maintain their professional capabilities through volunteer work than widening or enriching them. This is probably because they’ve been able to gain enough knowledge and skills already and their main goal is limited to maintaining competence.

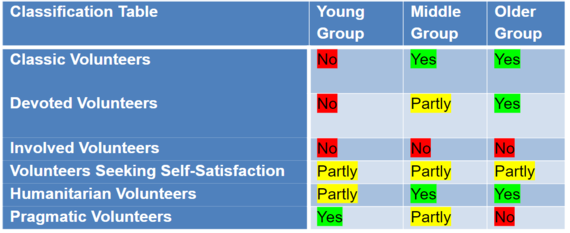

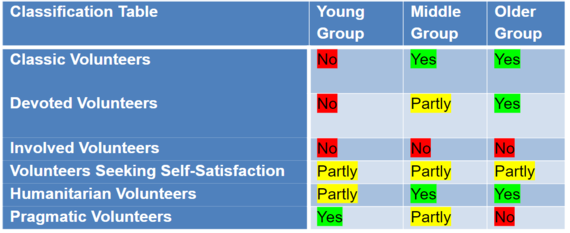

1.3.2. Volunteer Classification by Type

Middle and older age groups tend to fit the classic volunteer definition best because their main aim is to pursue valuable work for the public good. This requires putting in a lot of time. The young participants don’t put in a lot of time into volunteering, despite the fact that they also state they wish to make positive changes. This is due to time conflicts with school schedules.

The mature age group tends to fit the devoted volunteer definition best, as was expected. Despite the fact that they collaborate with numerous volunteer organizations, often they initiate volunteer work themselves.

In the table below there are no involved volunteers in any of the age groups. This type of volunteering has not yet developed in Armenia.

Those who seek self-satisfaction can be found in all age groups. People in this segment of classification seldom mention motives based on helping others. Hence, we can state that seeking self-satisfaction is only partially expressed in these groups.

All age groups fit into the humanitarian volunteer definition. However, it should be noted that, despite their desire, the youngest age group can’t fully be involved in volunteer work within this scope due to their limited experience and skills and not having enough time. Hence, by realistically evaluating their own possibilities, young people state other motives to volunteer.

Pragmatic volunteering is more prevalent in the youngest age group. Participants of this focus group don’t volunteer for self-oriented reasons, however, all of them state that many people in their age group volunteer to get mandatory paperwork or to enhance their resumes.

2. HOW VOLUNTEERING RELATIONS ARE REGULATED IN THE REPUBLIC OF ARMENIA

2.1. Legislative Acts and Laws

Volunteering activity in Armenia is regulated through separate legislative acts and laws aimed at regulating only a few fields in the volunteering sector.

Volunteering in Armenia is regulated through the following laws and legislative acts:

- Labor Code of Armenia

- RA Law HO-22-N on NGOs passed on December 16, 2016

- RA Law HO-424-N on Charities passed on October 8, 2002

- RA Government Decision N 274 on “Establishing Registration Procedures for Charitable Assistance for Charities and Volunteer Work” passed March 20, 2003

- RA HO-85-N Law on “The Status of Rescue Forces and Rescue Workers” passed May 25, 2004

- RA HO-265 Law on “Protection of the Population During Times of Emergency” passed December 2, 1998

- RA HO-176 Law on Fire Safety passed April 18, 2001

- Extract from the RA Government Session Minutes N 42 on “Approving the Concept of Forming and Developing a Social and Volunteer Rescue Movement in the Territory of the Republic of Armenia and the Events Program for Carrying Out this Concept” passed October 9, 2014

Article 102 of Chapter 13 of the RA Labor Code states that volunteer work and work carried out to provide assistance cannot be considered illegal. The terms and conditions for carrying out this kind of work are stipulated in the law.

Article 3 of the 2001 RA Law HO-424-N on Charity states that charity is voluntary, selfless, and legal (gratuitously or on preferential terms) material and spiritual assistance (hereof charitable assistance) to individuals, health and non-commercial organizations by individuals and legal entities, for the accomplishment of the goals specified in Article 2 of this law.

Article 7 of Chapter 2 of the RA Law HO-424-N on Charity states that the participants of charity are benefactors, volunteers, and recipients of charity (beneficiaries). Charitable organizations may serve both as benefactors and as beneficiaries.

Article 9 of Chapter 2 of the RA Law HO-424-N on Charity states that volunteers are those individuals, who gratuitously perform works for the benefit of the recipients of charity based on the goals of this law.

Article 14 of Chapter 3 of the RA Law HO-424-N on Charity states that charitable expenditures shall be defined as expenses associated with the implementation of charitable programs, the activities of volunteers, as well as management overhead.

Article 15 of Chapter 3 of the RA Law HO-424-N on Charity states that the title “Volunteer of the Year of Armenia” shall be conferred upon the individual who has worked as a volunteer for more than 365 hours during a year and who has worked voluntarily for more hours than any other volunteer during that year.

Article 17 of Chapter 3 of the 2016 RA Law HO-22-N on NGOs states that:

1. An Organization may, in conformity with its goals, have beneficiaries, as well as involve volunteers in its activities.

2. The beneficiaries of the Organization are the persons or groups foreseen by its statute. When regulating legal relations arising in connection with the involvement of volunteers by the Organization, the Law of the RA on Charity and the Labor Code of the Republic of Armenia apply to the extent these regulations do not contradict this Law.

3. If the duration of the work of a volunteer exceeds five consecutive days, then an Organization signs a voluntary employment contract with him/her.

4. The voluntary employment contract is an agreement between the volunteers and the Organization on the basis of which the volunteer, of their own accord, without remuneration and for a definite period of time, engages in voluntary work.

5. The voluntary employment contract specifies:

1) The year, month, date and place of conclusion of the contract;

2) The name of the Organization;

3) The title, name and family name of the person signing the contract on behalf of the Organization;

4) The name, family name and, if the volunteer wishes so, the patronymic of the volunteer;

5) The description of voluntary work and the job description, procedure, and conditions for carrying out the volunteering activities;

6) The rights and duties of the Organization and the volunteer;

7) Working hours;

8) Contract duration.

The voluntary employment contract may also specify other conditions related to voluntary work.

6. It is prohibited to involve volunteers in the entrepreneurial activities of the Organization.

Article 18 of Chapter 3 of the 2016 RA Law HO-22-N on NGOs states that the organization must maintain a record of its members and volunteers.

The Appendix of the 2003 RA Government Decision N 274-N on “Establishing Registration Processes for Charity Assistance for Charities and the Work Carried Out by Volunteers” stipulates the registration procedure for charity assistance and volunteer work done for the purpose of granting the titles of “Benefactor of the Year of the Republic of Armenia,” “Volunteer of the Year of the RA,” “Honorary Benefactor of the Year of the RA,” and “Honorary Volunteer of the Year of the RA.”

Within the framework of charitable projects, the registration process of charity assistance and the work done by volunteers is carried out by the Armenian Government’s Charity Program Coordination Commission (hereinafter Commission). The amount of charity assistance by benefactors (monetary and/or in-kind) and the hours of volunteer work are calculated between January 1 to December 31 for the given calendar year. The amount of charity assistance by an individual benefactor and/or the number of hours of volunteer work within the framework of different charity projects are calculated as the sum of the charity assistance or volunteer work done in the given calendar year. State bodies, charities and non-profit organizations provide information on charity assistance by an individual benefactor and/or volunteer participation in projects considered charitable to the Commission on January 31 of the year after the given calendar year. This has to include:

a) The name, patronymic, family name, place of residence, the monetary amount of the assistance and/or the monetary value of in-kind assistance and the name of the charity project.

b) The name, patronymic, family name, place of residence, ID number and serial number (individual passcode), the name of the charity project, number of hours of volunteer work, deadlines, and place.

The information provided by state bodies, charities and non-profit organizations is signed by the leader of a given body or organization and is stamped by the given body or organization.

During times of emergency, one hour of volunteer work is calculated at triple value.

The Commission registers that information in records kept for that purpose.

The Commission summarizes the information provided by the state bodies, charities and nonprofit organizations referred to in Article 5 of this Appendix and, if necessary, clarifies their authenticity.

The Commission, as stipulated in Article 15 of the Law on Charities presents the names of candidates for awarded titles to the Prime Minister of Armenia to present to the President of Armenia.

Article 1 of Chapter 5 of the 2004 RA Law on “Rescue Forces and Rescue Workers” states that rescue forces are created:

1) As expert forces, such as search and rescue, mountain rescue, snow rescue, gas rescue, fire fighting, water rescues, and other types,

2) As volunteer forces, such as search and rescue, mountain rescue, snow rescue, gas rescue, fire fighting, water rescues, and other types.

Article 3 of Chapter 12 of the 2004 RA Law on “Rescue Forces and Rescue Workers” states that volunteer rescue workers are those who go to an emergency site and carry out rescue work. When the professional forces arrive, the volunteer rescue workers fall under the direction of these forces and work under their supervision.

Volunteer rescue workers take time off without pay when they go to emergency sites to work. While carrying out rescue work, any damage done to the health or life of the volunteers is compensated by the state or state-provided insurance. Volunteer rescue workers who have gone to emergency sites by request of authorized bodies are exempt from carrying out their job duties within state and public spheres. If volunteer rescue workers work in emergency sites for up to 15 days within the given calendar year, then they are compensated by amounts set by the Government of Armenia.

Subparagraphs a) and b) of Paragraph 2 of Article 26 of the 2001 RA Law on Fire Safety correspondingly states that in the field of fire safety, local self-governing (municipal) bodies can voluntarily:

a) Provide education campaigns to residents for ensuring fire safety, including them in fire prevention and extinguishing work,

b) Support public fire protection associations.

Extract from the 2014 RA Government Session Minutes N 42 on “Approving the Concept of Forming and Developing a Social and Volunteer Rescue Movement in the Territory of the Republic of Armenia and the Events Program for Carrying Out this Concept” stipulates, among others, the state of a social volunteer rescue movement, the development of main tendencies, and the necessity of its regulation.

2.2. Proposed Bill on the Regulation of Volunteering Relations

Along with the currently existing regulations, state bodies have also developed several bills during the last decade aimed at regulating volunteering activity relations. The purpose of these bills was to harmonize regulations in the sector and to create a united legislative field.

One of these state initiatives was the bill on “Volunteering and Volunteer Work” proposed by the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs in 2017. This bill proposed to regulate volunteering relations and volunteer work, establish their main areas, principles, aims for volunteering and volunteer work, rights and responsibilities, as well as the legal foundations and characteristics of volunteering and volunteer work. Within this bill’s framework, volunteer work was stipulated as a non-compulsory activity done without compensation for the good of society, carried out within the bill’s established areas and/or employment and/or relating to the aims and principles set forth in the bill.

According to the bill, a volunteer is a citizen of the Republic of Armenia, a foreign citizen or a stateless person that carries out volunteer work based on a written contract outside working (or class) hours or during times established by the bill during work (or class) hours or if they’re unemployed (and not a student).

Volunteer work is carried out by a volunteer, as an individual or group, on their own free will for the general public good without concern for financial gain.

An individual or group doing volunteer work is a person or a group of people that carry out volunteer work and/or organize and/or take part in volunteer activities (campaign) set forth by the bill within the field and/or work set forth by the bill and/or relevant to the main aims and principles set forth by the bill for the volunteer work based on the rules set by the bill that is without a volunteer agreement on volunteer work.

Volunteer activity (campaign) is a one-time and/or non-permanent event by subjects of volunteer activity and volunteer work within the fields and/or work set by the project and/or relevant to the main aims and principles set by the project of the volunteer activity and volunteer work.

This project stipulates the following types of volunteer work:

1) Short-term: volunteer work up to two months

2) Mid-term: volunteer work from two months to one year

3) Long-term: volunteer work for more than one year

It stipulates the main forms of volunteer work:

1) Volunteer work by a volunteer organization within the framework of volunteer activity,

2) Volunteer work by an organization that engages volunteers within the framework of volunteer activity,

3) Volunteer work by an individual or group on their own accord.

2.3. International Experience in Regulating Volunteerism

Volunteerism is an integral part of a developing civil society and has its unique and decisive place in the formation and development of that society. It can be observed within economic and social contexts. Many international organizations, including the UN General Assembly and the European Parliament, call on their member states to foster volunteering and create legal foundations for its development.

However, the terms volunteer and volunteering today have no internationally recognized definition that countries can refer to. Different international organizations have tried to define and describe the main characteristics of volunteering. The most widespread is the definition by the International Labor Organization (ILO):

Activities performed willingly and without pay outside the volunteer’s household or family through any organization or through immediate, direct participation.

A legal definition for volunteering on the local level should be prioritized because it allows outlining the limits of volunteering, ensuring the accountability and measurability of such activities.

Since states tend to delineate different purposes for volunteering depending on political, economic and social conditions, legal approaches to volunteering are different as well. Nevertheless, there is one general issue regarding regulating volunteering: avoiding over-regulation. If we observe the experience of EU countries, there are three main approaches that stand out:

1. The absence of national legislation regulating the legal status of volunteers. This approach is used in those countries that already have an established volunteering culture. Sweden and the United Kingdom are in this category. For example, Sweden has avoided regulating this field for years. Any existing contradictions are solved through judicial means only.

2. Regulating volunteering through sectoral laws and legislative acts. Latvia, Kosovo, Poland, Bulgaria, and France use this approach. For example, France recognizes two types of volunteering: Bénévolat and Volontariat. The former does not require legal recognition, as a volunteer and the individual, whether employed or a student, can be involved in volunteering activities willingly. However, the latter requires legal recognition as a volunteer, which is regulated through different legislative acts.

3. Regulating volunteering within a single, separate, comprehensive law. Lithuania, Macedonia, Moldova and Slovakia have similar legal regulations. For example, Macedonia’s law on volunteering defines what volunteering is, the rights and responsibilities of the volunteer and host organization, as well as tax policies, mandatory insurance requirements and the spheres of the volunteer’s responsibility in the event of damages caused by the latter.

Generalizing these three models, the European Center for Not-For-Profit Law (European Center for Not-for-Profit Law, 2014) advises implementing:

a) The first model, if the country already has a formed volunteering culture,

b) The second model, if there is a need for immediate solutions in the field,

c) The third model, if there is a need to foster volunteering on a state level and if there are unharmonious requirements for the regulation of volunteering that can hinder the development of this sector.

It’s interesting that the Czech Republic implemented a volunteer certification institution through the law they passed in 2014 on “Making Additions to the Law on Czech Volunteering Services.” This is an official attestation certificate showing that an individual has taken part in professional training courses. This certificate is additional support for the unemployed to find employment.

In the field of regulating volunteering, a new but important initiative is the employment of disaster response mechanisms which foster the improvement and development of the management of spontaneous volunteering.

It should be noted that state intervention should not be limited to only creating and improving the management field. In order for governments to be able to ensure a collaborative atmosphere in the volunteering sector between state bodies, civil society, the private sector, unions and committees have been created in certain countries with the direct participation of state bodies, civil society and the private sector. There is also the experience of national and local centers that unite volunteers, host organizations and state representatives under one roof. This approach is implemented in Australia, Argentina, Brazil, Croatia, Egypt, Lebanon and Luxemburg (UN Volunteer, 2011).

3. RECOMMENDATIONS

Based on the data included in this policy paper, its analysis and conclusions, the following recommendations have been identified for fostering volunteering in the Republic of Armenia.

3.1. Recommendations for Policy Development in the Field

- Projects publicizing volunteering are necessary. These will be aimed at raising the public’s awareness. The lack of basic knowledge on volunteering does not encourage people to sign up for volunteering.

- Tools for encouraging volunteers in order to foster the continuity of participation in volunteering projects. Encouragement can be conveyed through letters of appreciation or by providing certain privileges which should include something tangible, like numerous discounts for example.

- Favorable conditions for field-specific volunteering which will imply possible involvement of volunteers who will be taking into consideration positive reactions to professional volunteering.

- A unified database of volunteers with all their information (not conflicting with personal data protection) which will foster:

1. Signing up to volunteer multiple times because it’s much easier to get people who already have volunteering experience to volunteer again compared to people who are signing up for the first time.

2. Eliminating the differentiation of fake and real volunteers because those volunteering “for a piece of paper” can not state their motives and instead of requesting a document simply provide their information.

3. Developing fact-based policies on volunteering based on statistical data.

- Due attention to the organization and systematization of volunteer work and if possible making the work more interesting.

- Universities and employers should include volunteer work experience in their announcements as a desirable condition.

- Information about volunteering in school courses that will represent volunteering as something positive.

- Meeting with students during which the characteristics of volunteering will be presented and getting involved in volunteer work will be encouraged.

- Widespread awareness campaigns that will present volunteering as a productive way to gain work experience, skills, and knowledge, taking into consideration high levels of unemployment.

- When recruiting and targeting volunteers, it is necessary to take into consideration the motives of the latter and propose relevant fields, types of employment and workplace. For example, propose more interesting, less laborious and temporary work for 14-20-year-olds, which will allow them to gain skills and experience in their everyday lives. Propose field-specific involvement to older age groups as a way to foster professional experience and obtain and maintain skills.

- Special training before participating in certain volunteer work (for example, fire fighting). Certification in this context gives tangible usability. For example, certification in physical preparedness can be seen as an advantage when starting to work in power structures or preference is given to those with volunteer experience when there are applicants with equal qualifications when getting accepted into university.

3.2. Recommendations on Legal Regulations of the Field

- Regulating the volunteering sector within the scope of one comprehensive law and establishing the main concepts of the sector.

- Taking into consideration that certain types of volunteering require a comparably stricter approach and that certain strict regulations may hinder other types of volunteering, establish regulations in a given volunteering field, including the rights and responsibilities of the volunteer and host organization, with the bodies regulating that field. It is recommended to observe volunteering based on the following field types:

– Spontaneous volunteering or volunteering for eliminating consequences during natural disasters and emergency situations

– Volunteering aimed at the prevention of disaster risks

– Social volunteering

– Volunteering within international collaboration

– Volunteering aimed at protecting the environment

– Cultural volunteering

– Scientific-educational volunteering

– Health care volunteering

– Sports volunteering

– Volunteering to pass free time aimed at raising social awareness on volunteering

– Community volunteering

– Volunteering in the field of defense

- Establish minimum volunteering ages, dependent on the type of volunteer work.

- Establish clear compensation mechanisms for damages incurred during volunteer work (for example, insurance) based on the type of volunteer work.

- Establish mechanisms for providing social benefits for volunteers.

- Establish management mechanisms for volunteering based on the type of volunteer work.

- Foresee steps that will be aimed at raising public awareness on volunteer work, as well as spontaneous volunteering during natural disasters and emergency situations.

- Observe volunteering as the most important link between school and labor markets and establish fostering mechanisms for volunteering. For example, create legal foundations for implementing volunteer certification by establishing a list of those fields where volunteer certification can be seen as work experience. This approach will foster an increase in employment within the youth.

- A unified electronic platform for volunteering which will contain information on volunteers, cover legislation on volunteering, the rights and responsibilities of volunteers and host organizations, include the type of certification for volunteering, the mechanisms for implementing certification and other information pertaining to volunteering. To maintain transparency in the field of volunteering, it is recommended to include current opportunities and plans in regards to volunteering within the unified electronic platform.

- Volunteer organizations should be obligated to maintain data transparency principles when engaging volunteers. They should publish volunteering announcements on the organization’s website within set deadlines, in online platforms and the unified electronic platform for volunteering.

- Volunteer organizations should be obligated to maintain equal principles when planning out volunteer engagement by observing volunteer engagement within the context of social inclusion, as well as equal participation. Volunteer engagement should be organized such that more vulnerable sectors of society, including people with disabilities, minors from low-income families, etc. will also have an opportunity to participate in volunteer projects.

- Mechanisms to encourage volunteering, including special badges that the volunteer can wear as a sign of the type of volunteer work they are doing and relevant achievements. It is necessary to give importance to volunteering through different events and the latter’s role in the development of the country.

Akintola, Ol. (2011). What Motivates People to Volunteer? The Case of Volunteer AIDS Caregivers in Faith-Based Organizations in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Health and Planning, 26, 53-62.

Attride-Sterling, J. (2001). Thematic Network։ An Analytic Tool for Qualitative Research. Qualitative Research 1, 3, 385-405.

Bussell, H. and Forbes, D. (2002). Understanding the volunteer market։ The what, where, who and why of volunteering. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 7 (3), 244–257.

Clary, G., Snyder M., Ridge R., et al. (1998). Understanding and Assessing the Motivations of Volunteers։ a Functional Approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 74։ 1516–1530.

Carpenter, J. and Myers, C. (2010). Why Volunteer? Evidence on the Role of Altruism, Image and Incentives. Journal of Public Economics. 94, 911-920.

Dolnicar, S. and Randle, M. (2007). What Motivates Which Volunteers? Psychographic Heterogeneity Among Volunteers in Australia. International Society For Third-Sector Research and The Johns Hopkins University. 18, 135-155.

Hibbert, S. Piacentini, M. and Dajani, H. (2003). Understanding Volunteer Motivation For Participation in a Community-Based Food Cooperative. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 8 (1), 30–42.

McDonald, M. (2002). Marketing Plans – How to Prepare Them, How to Use Them, 4th edition. Oxford։ Butterworth-Heinemann.

Rehberg, W. (2005). Altruistic Individualists։ Motivations For International Volunteering Among Young Adults in Switzerland. Voluntas, 16(2), 109–122.

Wandersman, Ab. and Alderman, J. (1993). Incentives, Costs and Barriers for Volunteers։ A Staff Perspective on Volunteers in One State. 67-76.

Ziemek, S. (2006). Economic Analysis of Volunteers’ Motivations։ a Cross-Country Study. Journal of Socio-Economics 35, 532–555.

UN Volunteers (2011). Drafting and Implementing Volunteerism Laws and Policies։ A Guidance Note. 15-20.

European Center for Not-for-Profit Law (2014). Volunteering։ European Practice of Regulation. 1-16

This project is funded by the UK Government’s Conflict, Stability and Security Fund.

The opinions expressed are those of the authors’ and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the UK Government.