I was a postgraduate student in Moscow. I called my mom, it was February. She said, “Do you know what’s going on here? There are rallies and of such scale!” There was a hint of excitement in her voice, because something was changing, it was history. The situation was unfamiliar, unexpected but also troubling. Then Sumgait happened and we, the Armenian students of Moscow State University began collectively writing letters on behalf of the members of the komsomol [1] trying to get the system to budge internally. We wanted the “central” media to cover the events in a “normal” and “balanced” manner; in our opinion, that which they considered “balanced” was pro-Azerbaijani.

This was the beginning of an ongoing process that lasted years, in fact, until independence; collect what the media was writing about the Movement and the conflict, compile personal archives, and write responses, articles, letters. Many families collected similar archives, some of which were later burned in wood stoves in the cold years. [2] People were angry to the point of madness at the way the “central” media was presenting the unfolding events in the region.

Later two students arrived from Yerevan State University’s department of Oriental Studies and with our assistance filled a large auditorium at Moscow State University. They spoke about what was taking place in Armenia and why. It was astonishing that it was possible to fill an auditorium without an order from “above” and so many people came, including professors with ranks. It was even more astounding that our dean, Mary Kochar had sent these young men from Yerevan on state funding so that they could come and explain why the revolution, which was breaching the rules of that state, was taking place. At the time, this was still being done in the name of “perestroika.” In other words, the idea was to present the events as an expression of the spirit of reforms initiated by Gorbachev, rather than a revolt. During the course of that year, the “center” did everything possible to ensure that this desire and the attempt to adapt evaporate and for the Movement to gradually transform into one for independence.

I was captivated by the qualities of those two students – their ability to speak, to persuade, argue and disagree. They reminded me of those eloquent early Bolshevik propagandists. Both of them no longer live in Armenia… Moscow was divided; the overriding majority of the journalists and Orientalists I knew did not want to understand what the Armenians were doing, their predisposition was that of hostility. That is what I felt back then, maybe they were right to be skeptical. But for example, people in the world of cinema were completely sympathetic and within their embrace, I finally started feeling that my wounds were finally starting to heal. Maybe that too was a deception.

I came to Yerevan that spring. I participated in the protests that had restarted. I don’t know of a good timeline to recall the months and days of those years, one where I could insert my memories. Then I went back to Moscow, and returned again this time for three months in the summer.

Up until then, I had rarely experienced the presence of such a massive group of people. There had been the occasional rock concert that had attracted substantial crowds. Prior to this, there had been similar and somewhat more impressive instances of people marching on the street after a football match that would at times transform into a rally; happy that the home team had won or angry that it had not. I could not have been present at the 1965 protests[3] because of my age, but I had heard my parents’ stories. Soviet official rallies, May First, etc., could have been happy occasions but they didn’t emit that feeling. They had already started celebrating “Erebuni-Yerevan,” another rare instance of mass participation but in no manner a match for the rallies at Opera Square. This was a new historic era.

Being present at the rallies, and they were massive, would generate contradictory feelings in me. At first, an enchanting, mystical sensation; my emotionality would intensify. “This is my people.” There was a scent of sanctity during those first meetings. Until then, I had only experienced that scent in empty churches – Hripsime, Geghard, Harij, Ohanavank, Haghpat… then, years later, I caught the scent in Karabakh and also in Abkhazia. I’ve gotten a hint of it in other places that wanted to be independent but are not, places like Kabarda … The last time I experienced that scent was during the meetings prior to March First.[4] It was nostalgic. All of our other movements, the ones that I was present at, the scent was not the same, though the one at Electric Yerevan, the night of the water cannons, right before they were unleashed, came pretty close.

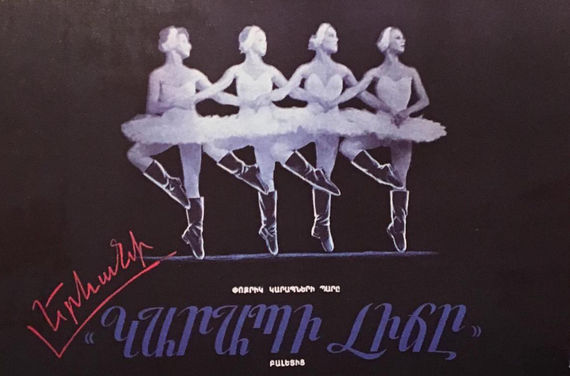

Form the poster exhibition at PANM First Congress, November 4, 1989.

The distress: Because everyone has been standing for hours and without knowing what is going to happen, they are waiting for news.The disbelief: How did everything change suddenly? Up until then, the people were silent, exploited, fearful, deceitful, had become immoral, and all of a sudden, this! Where are the tsekhaviks?[5] Why is the party, the KGB, the police allowing this? “The thieves announced that they are joining the protest and during the protest will not rob a single empty house.” Hurrah ! U-ni-ty

I am trying to relay my emotions now the way I experienced them at the time, episodically. I had no opinion as to what should be done, how to do it properly, I did not have theoretical knowledge of what was happening. I had no interest in politics other than that the Soviet Union was a dirty, unjust, pointless, bloody, completely false system (I had secretly read Solzhenitsyn’s “Gulag Archipelago” a long time ago, probably when I was 14, and knew of the sufferings of my family and their friends during the Stalin repressions from the tales of my parents well enough to consider that I understand the Soviet essence to its depths). My surrounding, save a tight circle of close people, was amoral, corrupt and cynical. “Perestroika” was a good thing, if it stayed on the right track, though I did not believe in it much but I was happy that the “center” started allowing freedom of speech and the story of the Soviet terror was being told. “Perestroika” was stuck in Moscow, in the “center.” There was no trace of it and of free speech allowed by it in Armenia for a long time. When Haik Kotanjyan, the secretary of the Hrazdan Regional Party Committee criticized Demirchyan[6] and was consequently dismissed from his post, I considered this a major event. As for what could be done about Karabakh or that Armenia could possibly be independent – these were not ideas I entertained in the beginning. I wanted the Soviet Union to be democratic, that was all.

The other feeling that quickly took shape as I was standing at the rallies for hours, was that of my irrelevance there. Staying longer than necessary at Church is futile. Something which I could not formulate back then about what I was feeling, I can express today as the following: while I understood that on the one hand this was a historic process and there was nothing to stop it, I did however, feel that the people standing there for hours, days, weeks, were wasting time. That when they are standing there, all productivity is suspended, they are not working. They are wasting energy. The factories, the Republic had come to a halt. That for the first time since the Genocide people had accumulated a certain amount of savings; that the masses had accumulated resources to push forward for a month or two without having to work, but that would run out and the people would face neglect, if not starvation or perhaps indeed starvation. Because in the midst of idleness, the factories, the railway, science, the university, all the industries would be shut down, rust, come to a halt, break down, become obsolete because these are permanent, non-stop processes; if they are severed for a while it is not possible to put them back.

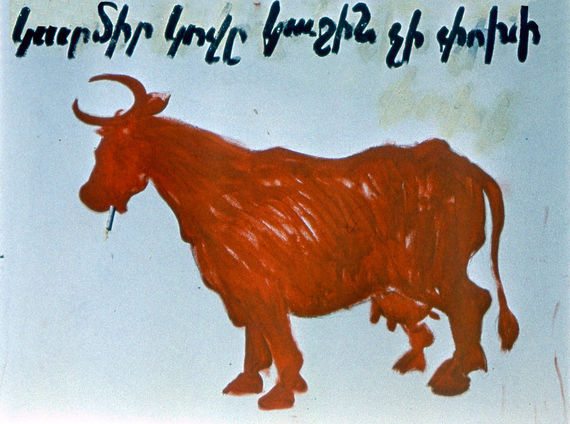

“The red cow does not change its skin.” Poster from Opera Square, July-August, 1988.

Many young people consider those days to be the best of their lives, and rightfully so. There was a strange, almost erotic celebration of unity and freedom. And who says a nation has to always be serious and responsible, without joy, delight and celebration. But I’m somewhat brooding probably, seeing them I would think – now what? The old is being destroyed with such delight and ease and who will be responsible for building the new? Building something is not only excitement and skipping class… or the readiness to sacrifice oneself, even in a heroic way; it is still not building the new…

Some of these young people died in combat and became heroes, others passed away, some left the country, some became disappointed forever, others lost their good name and some, to this day, are the pillars of this country.

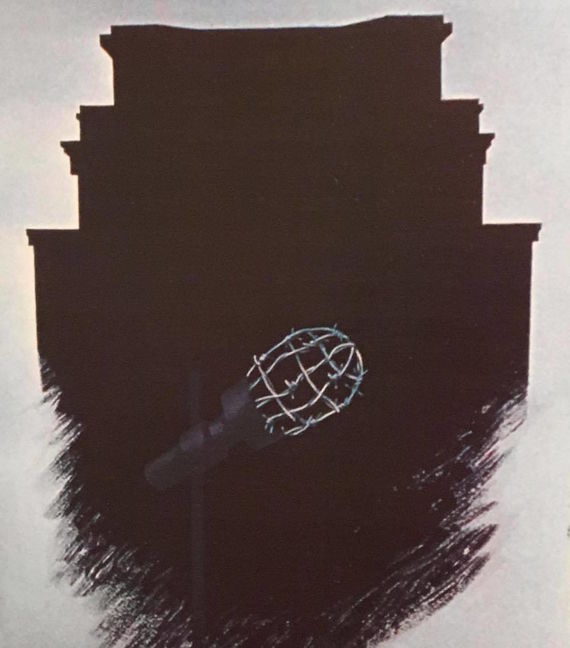

From the poster exhibition at PANM First Congress, November 4, 1989.

But history is like that, it gives birth to leaders, who appear in roles they could not have imagined before. Could the intellectual Trotsky, let’s say when he was 14 years old, imagine that he would become the War Minister of the Bolsheviks? Could the prose writer Vano Siradeghyan, when he was 14 years old, imagine that he would become the Republic of Armenia’s Minister of Internal Affairs…?

“Do they know how to lead?” I would wonder while watching them. “Do they have command of the secrets of leadership?” I didn’t and would never think to take a step in that direction without knowing a little bit, without learning. Up until then, the leadership of the Communist Armenians was another matter: they were not independent, they were appointed, and that is much easier, because ultimately the final responsibility is not yours. “Where had they learned? At school, while organizing their classmates to skip class? Was it an innate talent…?”

However, I deemed that those ‘boys’ were surely better than the careerists catering to the rotten Soviet system. The boys were intellectuals: historian, physicist, talented writer. We heard a lot of gossip about them: a group of them had a love for playing poker, the other, chess, being overly fond of women the third, the fourth were KGB and so on. But in those days, “our boys” were the object of collective love. They had come to be saviours in a situation where no one understood what was to be done.

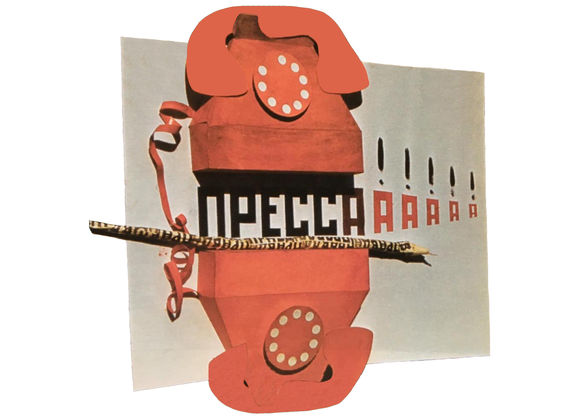

“Press.” Poster from Opera Square, July-August, 1988.

Coming from a family of persecuted intellectuals, historically and genetically I knew that no power could ever rule justly in our region and if one ever tried, it would immediately be eliminated. Were the boys any different? They were taking steps that were either right or wrong, for some it was just, for others it was unjust. They were obliged to take those steps (for example lead the provocation to be able to withstand it, lead the rally to the airport because the people were already headed that way). The choice was not so much laid out by them but rather by history; the people and events were leading them by their nose and demanding that they reactively respond to this or that challenge. Hrant Matevosyan, understanding the extent of one’s capacity would say, “We act based on the extent of our lack of understanding.” Nothing was prepared, there was no time to seriously plan, the old world was crumbling without waiting for plans to be made.

Poster from Opera Square, July-August, 1988.

Footnotes: