As Azerbaijan’s blockade of the Lachin Corridor is now in its second month, all schools in Artsakh (Nagorno-Karabakh) were shut down indefinitely starting from January 19, 2023, because of the rolling electricity blackouts and shortage of natural gas supply. Earlier, on January 7, Artsakh’s Ministry of Education, Science, Culture and Sports had temporarily closed dozens of educational centers due to food shortages. According to Artsakh’s Ombudsman, 41 kindergartens, 56 pre-school groups and 20 full-time educational institutions had suspended operations indefinitely, leaving 6828 children without access to daycare and education.

Meanwhile, students, educators and parents have to navigate new challenges.

“We have already sort of come to terms with reality,” says 15-year-old Nare Arushanyan. “We know what awaits us — years without electricity, gas, hunger — but no matter what happens, we have to stay strong. That’s all we can do.”

Vera Mkrdumyan, 14, from Stepanakert, whose parents are currently stuck in Yerevan unable to return home, said that when classes were taking place, the challenges were with food and transportation. “Since the 2020 war, we no longer have a school cafeteria, so we would normally buy lunch from the bakery nearby where they make pizza, hot dogs and stuff like that. That place is closed, the nearby stores are emptied out and there’s nothing to buy for lunch at school.” If they were hungry, they would have to wait until they got home to eat whatever was available.

Vera says she isn’t worrying yet as her family has enough food supplies for a while, but if the blockade lasts for much longer, the consequences will be much more substantial. “[Food] will run out eventually.” A picky eater, she admits that the shortage of food is the biggest challenge for her. “When I talk with my mom on the phone, she says ‘Eat whatever is available so as not to make your grandma angry.’ I’m craving oranges, but under the blockade I have learned to eat whatever there is. You can’t be capricious about it anymore.”

The emotional spectrum of young people in Artsakh seems to range from powerlessness and despair to resilience and perseverance. “Small children don’t quite get what’s going on. But the older kids feel disheartened. No one really had a good New Year — there was no Santa and no presents for many of them,” says Nina Shahverdyan, an English teacher with Teach for Armenia from the village of Herher, who previously worked in the village of Aghavno, currently under Azerbaijani control. Nina’s school administration reduced class time from 45 to 35 minutes, canceled the lunch break and suspended P.E. classes so that students had enough energy until the school day finished, since not everyone has food to bring for lunch. Nina notes that despite the circumstances, student performance and attendance didn’t suffer. They even had one extra student who was visiting relatives in Artsakh before the blockade and was studying in Herher until the road opens again.

Nina explains that in contrast to villagers who grow much of their food themselves and still have supplies from the harvest season, people in Stepanakert rely on grocery stores. At the same time, villagers’ food is only enough to feed their own families and is not for sale. Despite this, there currently seems to be a sense of community and solidarity. Nina, originally from Stepanakert, would normally buy groceries from the store. Under the blockade, however, neighbors have been sharing eggs, meat and wine with her.

Another difficulty Nina currently faces are the periodic outages of electricity and, consequently, the internet [1]. “Now you can’t plan your day as you wish, but rather when there’s power. It’s inconvenient. I normally prefer to work in the evenings, but now I just wasted two hours without the internet and wasn’t able to complete my lesson plan.”

Rolling blackouts and the absence of consistent internet affected public schools and private educational centers alike. “The blockade negatively impacted us as well,” says Diana Balughyan, the photography workshop leader at tech-based learning center TUMO Stepanakert. “Because of blackouts students weren’t able to do their self-learning activities or participate in the workshops.” Since TUMO doesn’t use gas, blackouts mean there’s no heating either.

Diana says that she and her colleagues are making every effort to arrange make-up sessions for missed classes, but with the shortage of fuel, it doesn’t solve the issue of transportation for those students who come from other regions of Artsakh. Normally, students from Martuni, Martakert and Askeran complete the self-learning component of their TUMO education from local TUMO boxes, and, after successful completion, travel to Stepanakert for month-long workshops. Given the circumstances, workshops have moved online, which, according to Diana, is not as effective as the physical presence of the workshop leader and negatively impacts students’ final outcomes. Due to the blockade, there are no ongoing special labs either, which are normally led by professionals invited from Armenia and abroad.

“I notice many students are disheartened due to the food shortages and the absence of some of their parents who are unable to return to Artsakh, but before each session, my colleagues and I encourage them not to give up or panic and instead work even harder, produce even better results and use all of our resources to raise awareness about what’s going on.” Despite the challenges and uncertainties, Diana notes that currently TUMO is the only place where she feels that everyone wants to work and create something. “This is a place where students can distract themselves for a while and be creative and it’s largely thanks to the efforts of the staff who make sure to be there for them.”

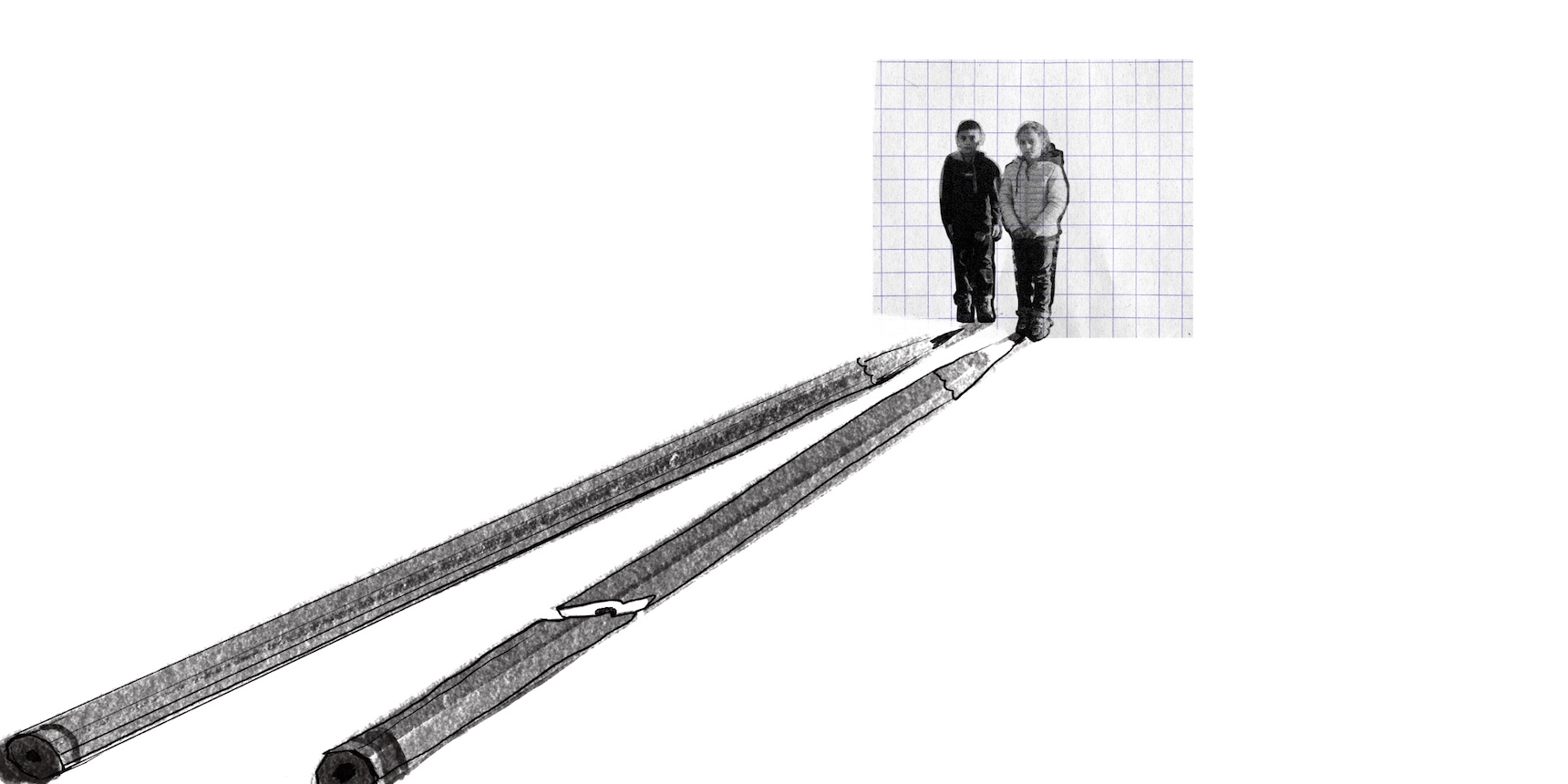

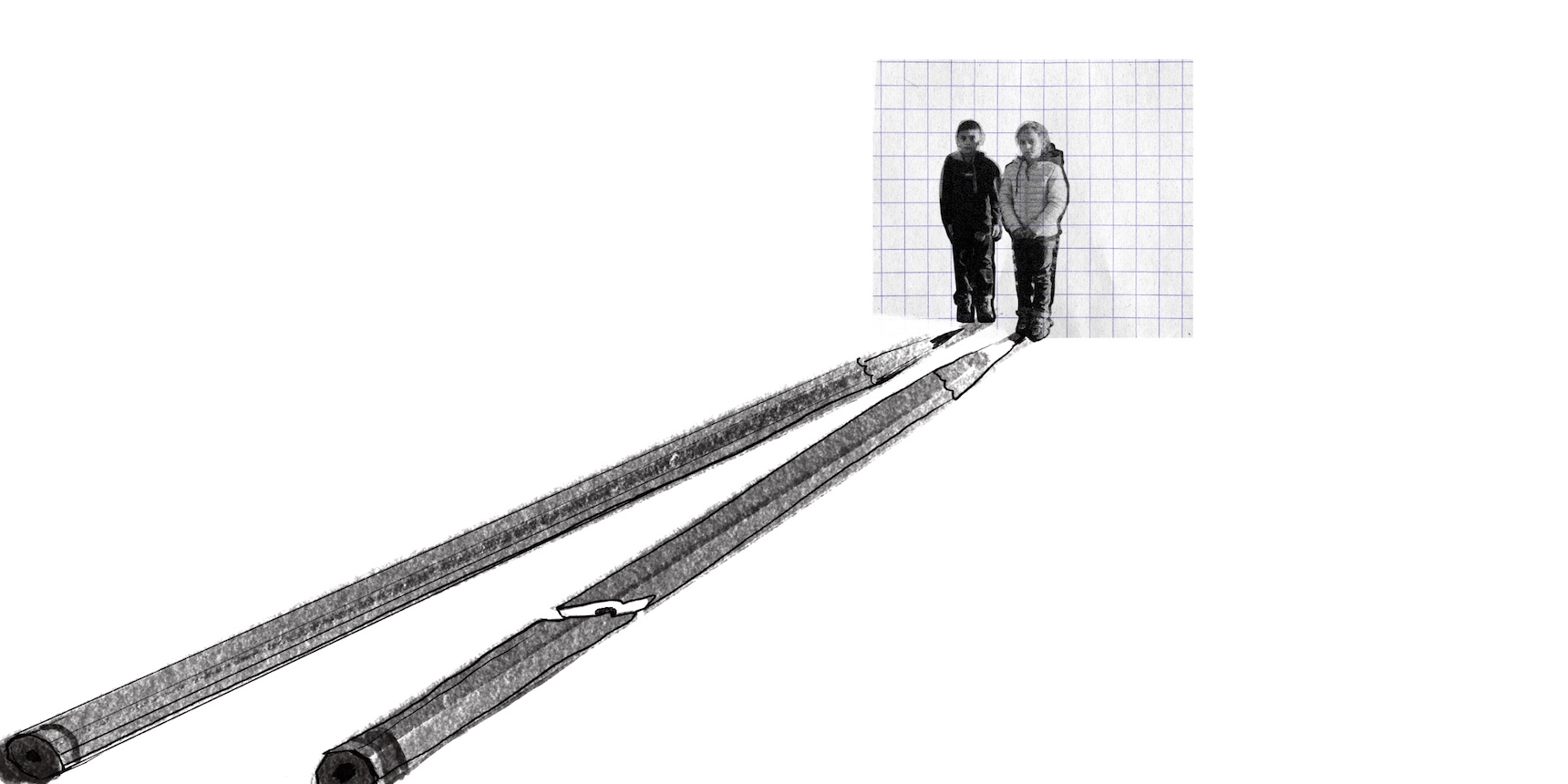

While educators like Nina and Diana were doing their best to keep their students’ spirits high, motivate them and deliver a quality education, Ashot Gabrielyan from the village of Kolkhozashen, Martuni region, was attempting to do the same thing for his students, but from Yerevan, over 300 km away. Originally from Askeran, Ashot joined Teach for Armenia after the 2020 Artsakh War since he believed “change starts with education.” To ignite that change he decided to apply his knowledge and experience into educating youth.

Ashot, who teaches English and social sciences in Kolkhozashen, left the country on personal business on December 12, 2022 with a plan to return on December 16. The Lachin Corridor blockade however, forced him to stay in Yerevan and find alternative ways to teach his classes. “Since I wasn’t able to return, students had to miss the subjects I taught and naturally the end of the semester made things even more difficult. Thanks to the close cooperation with the school administration, we were able to organize all the final exams and successfully complete the semester.”

Two of Ashot’s senior students normally stay after school for additional tutorials to prepare for university entrance exams. Under the blockade, they switched to online classes, which, given the recent internet outages and rolling blackouts –– extended from two to four hours –– were not as productive. “Right now we are trying not to fall behind too much, using every opportunity to study online, hoping that the road will open soon. Apart from this, two of my students were supposed to go to Yerevan, where they would participate in a very important selection process for their future, but unfortunately they are unable to do so,” says Ashot, noting that while his students do worry, they also possess a lot of strength. Beside teaching, Ashot, along with his students, has founded the “Jane [Ջանէ]” youth center, where they carry out various community projects and organize events. With Ashot’s physical absence, his students keep the youth center alive. “They help the elderly and organize different events in the village to show their perseverance,” says Ashot, who feels proud of his students for not giving up, studying even harder and voicing the challenges that people in Artsakh face.

While trying to be a support system for his students, Ashot has to deal with his own worries and emotional ups and downs, away from his own family and community. “I have quite mixed feelings right now, because I do not know how to feel in this situation. My family is in Artsakh. I am worried about them. My students, neighbors, colleagues, and friends are all in Artsakh. I understand that we must be strong, have strength and be able to sympathize with those who are now in Artsakh. But I also understand that if I were there right now, I would be calmer knowing the situation from within.” Doing his best to educate from so far away, Ashot is looking forward to returning to Kolkhozashen.

“Kolkhozashen plays such a big role in my life that it is difficult to put into words,” Ashot says. “That small, stony village, the birthplace of the famous ‘Karabakhtsi’ song, attracted me from the first day. The village has given me human connections that will stay with me for the rest of my life. There is so much to see, listen to and experience in Kolkhozashen that I will do everything to go back again and continue to work with my students, who are so full of positive energy and warmth in them. They possess leadership that can light up the entire world. I have the best students, village, neighbors in the world and I really don’t know how I got so lucky.”

Footnote:

[1] On January 9, the supply of electricity from Armenia was cut due to damage on the Goris-Stepanakert power line, which passes through the territory currently occupied by Azerbaijan. The Azerbaijani side prevents any emergency and restoration work. Artsakh authorities have since resorted to rolling power blackouts and urged people to reduce energy consumption.

Also see

November 2022

Displaced Voices: The Story of Hratsin Ohanyan

Although the only things Hratsin Ohanyan has left of her native Hadrut is a photo album and her dialect, she stubbornly refuses to let her status as an internally displaced person pull her down. She is resilient, hopeful and fearless.

Read moreOctober 2022

The People of Artsakh: Resilience and Anguish

A young Armenian woman, born and raised in Stepanakert, the capital of Artsakh, reflects on the changing, contradictory reality of her hometown two years after Azerbaijan launched a devastating war.

Read moreMay 2022

Despite Everything, Artsakh Celebrates

The resilience to persevere through unspeakable trauma was embodied by the tenacity to celebrate the May 8 and 9 holidays in Artsakh with a full schedule of events.

Read moreDecember 2021

Healing War Trauma With Art Therapy

A new program is implementing art therapy classes to help children in one of Armenia’s poorest regions cope with the trauma of war and process the barrage of negative news and feelings.

Read moreOctober 2020

The Children of War: On the Brink of Life and Death

Children also became a target of Azerbaijan’s large-scale military aggression during the 2020 Artsakh War. Their basic rights to life, health, family and community were consistently violated.

Read more