Since the beginning of 2022, Azerbaijan and Armenia have exchanged 5- and 6-point proposals for peace and normalization of relations respectively. In light of the OSCE Minsk Group crisis, recognized by the expert community, the wider public, and its own co-chairmen, there have been two other tracks of mediation between Armenia and Azerbaijan, one facilitated by Russia and another one by the European Union. The possibility of a peace agreement between Armenia and Azerbaijan is under consideration, along with the delimitation and demarcation process, as is the unblocking of communications.

This article attempts to suggest a way forward for the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict given the current situation to ensure security guarantees for its Armenian population, and make progress in the conflict’s resolution.

The Need for Grouping Issues on the Peace Agenda

To avoid an impasse in a fragile and dangerous status quo, it would be wise to cluster the different problems of the Armenian-Azerbaijani agenda of peace and normalization of relations –– delimitation of borders, unblocking of communications, addressing humanitarian issues and ultimately resolving the Artsakh (Nagorno-Karabakh) conflict. There are already different formats created for unblocking communications, and delimiting borders and providing for border security, which means mediators – whether Russia or the EU, have already begun a grouping of the issues.

In particular, as discussed in this article on the principles for delimitation and demarcation, the Nagorno-Karabakh issue must be considered separately from that of Azerbaijan’s territorial integrity. Azerbaijan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ reaction to Lavrov’s June 9, 2022, statement addressing the occupation of Parukh village by Azerbaijani Armed Forces in March, confusion over that statement in the Armenian expert community, and the Russian MFA’s subsequent editing of Lavrov’s statement demonstrates that there may already be a common understanding on this issue, even if the sides most likely have different reasons and objectives for it.

Clustering the Conflict’s Problems

The Nagorno-Karabakh problems comprise a range of issues, including issues around status, security, governance, human rights, development and humanitarian issues. Lessons learned from 28 years of negotiations have shown that attempts to find package solutions for all issues failed between the first and second Nagorno-Karabakh wars. As the perspectives of the parties to the conflict have been irreconcilable over Nagorno-Karabakh’s status, focusing on it and making other issues derivative from it in the interwar period led to a deadlock, and ultimately, to a new war. Moreover, the war in Ukraine demonstrated that even recognized sovereignty is not a guarantee against military aggression. Therefore, the change of “security through status” to “security and rights before status” as PM Pashinyan suggested in April 2022, is reasonable and pragmatic. However, it should not mean recognition of Nagorno-Karabakh as part of Azerbaijan, as it has been perceived by some circles both domestically and internationally, but rather suspending the discussion over status until guarantees for the security and the rights of its population are put in place in a sustainable manner.

Azerbaijan’s Rhetoric and its Dearth of Constructive Proposals

There is a clear discrepancy between the rhetoric of the Azerbaijani leadership and public figures meant for international and domestic audiences, and even for the international audiences within the same time period. They make statements about a peace agenda, while threatening Armenians with a new war and inciting ethnic hatred towards them at the state level. Azerbaijan’s actions since the 2020 Artsakh War and especially the period following the November 10 ceasefire statement have signaled its intent of either another military offensive or creeping advancement of its troops, resulting in ethnic cleansing of Armenians in newly captured territories and creating unbearable living conditions for Armenians through a manmade humanitarian crisis, all the while calling the self-governing institutions of Nagorno-Karabakh “separatist groups.”

It is obvious that Azerbaijan is trying to capitalize on its military victory. However, Azerbaijan’s unconstructive behavior and aggressive rhetoric cannot be normalized by the international community, and some red lines were signaled in the May 31, 2022, statement by the EU.

If Azerbaijan was able to justify launching the war in 2020 and its violation of UN and OSCE fundamental principle on the non-acceptability of the use of force by the restoration of its territorial integrity, that argument is no longer valid as it captured not only regions surrounding Nagorno-Karabakh, but also part of the former Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO) itself. Moreover, even the manipulation of the notion of territorial integrity has not given a green light to any state to conduct ethnic cleansing or oppression of an ethnic group under its jurisdiction. In accordance with the UN General Assembly Resolution 2625 (XXV) adopted in 1970, “every State has the duty to refrain from any forcible action which deprives peoples […] of their right to self-determination and freedom and independence[…]The use of force to deprive peoples of their national identity constitutes a violation of their inalienable rights and of the principle of non-intervention.”

Armenians have always constituted a predominant majority of the population of the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Region (89.1% Armenians and 12.59% Azeris in 1926 and 75.9% Armenians and 23% Azeris in 1979). Nagorno-Karabakh’s claim for self-determination cannot be considered a violation of Azerbaijan’s territorial integrity. First of all, it was never part of independent Azerbaijan––only Soviet Azerbaijan. Secondly, the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 1244, which confirms the territorial integrity of the Former Yugoslavia and Kosovo as part of it; however, it did not prevent the International Court of Justice from concluding that Kosovo did not violate international law by its unilateral declaration of independence.

The OSCE Minsk Group co-chairs have not considered Nagorno-Karabakh as part of Azerbaijan but a territory the status of which must be determined based on compromise. Any further military aggression by Azerbaijan on Nagorno-Karabakh or Armenia proper will lead to Azerbaijan’s stigmatization in the same manner as that of Former Yugoslavia and Russia for their use of military force respectively in Kosovo and Ukraine. If Azerbaijan carries out more ethnic cleansing of Artsakh, whether through military force or making them leave through softer methods, not only Azerbaijan but the international community will suffer a huge reputational loss, constituting another major blow to the international order.

Armenia’s Role

Some believe that since Armenia lost its role as Artsakh’s security guarantor and Russia has taken that role over through its peacekeeping contingent, Nagorno-Karabakh has become an issue between Russia and Azerbaijan. Since November 9, 2020, it is not clear how much leverage Armenia has over the Nagorno-Karabakh issue. The official positions of the Republic of Armenia and Artsakh authorities don’t always coincide. Armenia has no right to decide Artsakh’s future, since it is not a territorial dispute between Armenia and Azerbaijan but an issue of self-determination of Armenians in Artsakh. The local authorities of Nagorno-Karabakh have repeatedly stated they would not accept to be under Azerbaijan’s control. The right of Artsakh Armenians to determine their future has been recognized by major Western interlocutors, in particular by U.S. Ambassador Lynne Tracey in May and Special Envoy Toivo Klaar in June 2022.

At the same time, Armenia continues to remain an agent for Artsakh in diplomatic negotiations since the latter is not directly involved in them. Armenia also continues to economically subsidize Artsakh in the absence of international assistance to the territory. Armenia has no moral right to abandon Artsakh Armenians and has an obligation to maintain its role.

If we compare the Nagorno-Karabakh issue with comparable conflicts, such as the one in Kosovo, Albania has been disengaged from direct involvement in the resolution of Kosovo’s status since the 2000s, however, at that point the international community, including the UN, NATO, EU and the OSCE, had established a large presence in Kosovo, was providing security, political and development support, the process for the conflict’s settlement was on track.

In contrast, Artsakh was abandoned by the international community in violation of the UN’s “Leave no one behind” principle. There has never been any international organization to contribute to peacekeeping, a political resolution, institution-building or development in Artsakh. Even humanitarian assistance to it has been limited to the ICRC and HALO Trust. Unlike Kosovo or Timor-Leste, Artsakh has built its governance institutions and organized its elections without international assistance. The November 2020 ceasefire deepened its isolation further.

Issues of Status, Governance and Human Rights

If it has been impossible to resolve the issue of the status of Nagorno-Karabakh in a much more favorable geopolitical environment, it would be ambitious to try to resolve it in the current polarized and turbulent environment, and it will once again lead to deadlock. Therefore, the status issue should be suspended for several years, until the International Court of Justice makes a decision in relation to the Application of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (Armenia v. Azerbaijan). Meanwhile, Azerbaijan should prove its compliance with the provisional measures ordered by the ICJ to protect certain rights claimed by Armenia, and refrain from any action, which might aggravate or extend the dispute. Armenia should also ensure its compliance with the provisional measures ordered by the ICJ in relation to mirroring claims by Azerbaijan. Any violations of provisional measures by either Azerbaijan or Armenia should be reported to the ICJ.

Even after Armenian Prime Minister Pashinyan referred to the need of “lowering the bar of status”, the Azerbaijani authorities did not offer any status to Nagorno-Karabakh except for giving vague hints about cultural autonomy. The model of Aland Islands circulated by some Azerbaijani analysts seems superficial and ingenuine, since Azerbaijan, one of the most autocratic countries in Eurasia, cannot be compared with the most democratic Northern European countries.

Azerbaijani authorities have also not offered any governance models and guarantees for human rights. They have only made vague promises that ethnic Armenians will have the same rights as other citizens of Azerbaijan, and that they will receive cultural and social rights. Limiting the wide range of universal human rights to only cultural and social rights while ignoring political rights and civil liberties is unacceptable. According to all relevant international organizations and watchdogs, Azerbaijan’s human rights record is abysmal, and Azerbaijani authorities are even documented to practice transnational repression toward Azerbaijani activists critical of the Azerbaijani government. In spite of its increased isolation, Artsakh is much more democratic than Azerbaijan. Simultaneously, Azerbaijan has been depriving Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh of social and cultural rights by creating a humanitarian crisis in February and March 2022, destroying and appropriating Armenian cultural heritage and distorting history.

The Azerbaijani leadership and public figures have stated that Armenians can stay in Karabakh as Azerbaijani citizens. This sounds more like an ultimatum than an offer. What will happen to them if they do not accept Azerbaijani citizenship? Will they be massacred or deported from their indigenous land, or allowed to stay without rights and freedoms?

In this context, the self-governance structures and institutions of Nagorno-Karabakh should be preserved without disruption until the status issue is addressed. Once there is a proper international presence in Nagorno-Karabakh, international organizations may receive a mandate to assist with capacity-building and reforming institutions as they have in other conflict and post-conflict zones.

Security and Peacekeeping

The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict has seen two large-scale wars, in 1988-1994 and 2020, and a smaller war in 2016, all to impose a military solution to the conflict. The conflict’s history also includes several massacres between 1920 and 2020 . Several comparable conflicts examined in Part II of this series demonstrate that no contemporary inter-ethnic conflict with high intensity, armed clashes, threat of ethnic cleansing and military aggression has been de-escalated or resolved without international guarantees for security and human rights. UN peacekeeping missions help countries make the difficult transition from conflict to peace, after which UN political or peacebuilding missions help with political dialogue and peacebuilding. Regional organizations such as the African Union, European Union, NATO and the OSCE have taken up their share of responsibilities in ensuring peace, security and rights . Multinational peacekeeping forces have been operating for decades and are still maintained in Kosovo and Cyprus, and in Bosnia and Herzegovina and East Timor were withdrawn when they were not needed anymore.

Two major violations of the 2020 ceasefire – the capture and depopulation of two villages and a strategic mountain in Hadrut region in December 2020, and another village and a strategic hill in Askeran region in March 2022 demonstrate gaps in the current peacekeeping arrangement in Artsakh. In particular, they lay bare the uncertainty of the peacekeeping mission’s legal mandate, lack of clarity in rules of engagement and reporting mechanisms, the problem of reliance on only one state for security, and the exclusively military nature of the mission.

Russia mediated the ceasefire and its peacekeeping contingent was deployed as a peace enforcement operation to stop the 2020 Artsakh War. Russia is continuing to play a major role in negotiations between Armenia and Azerbaijan, and the Russian military contingent has been the only security guarantee in Nagorno-Karabakh trusted by local Armenian authorities in the absence of explicit interest by any other international actor in protecting their security.

Peace operations are not static and rigid but are dynamic arrangements dependent on the evolving situation. Peace enforcement is a subset of peace operations, in which military force is used as a tool of coercive diplomacy to terminate an ongoing conflict, implement a ceasefire, or create a secure environment for other elements of operations to succeed such as classic peacekeeping operations succeeded by political and peace-building missions.

Examples include the NATO intervention in Kosovo in 1999, after which KFOR remained as a defense force while a large UN peacekeeping mission followed, including the OSCE as its institution-building and the EU as economic rehabilitation pillars, later replaced by the UN political mission and the EU Rule of Law Mission. In the Central African Republic, a unilateral Sangaris operation was deployed by France to stop sectarian violence and civil war, followed by the AU and EU forces, and later on – by a large UN peacekeeping mission and the EU Military Advisory mission.

Attempts by Azerbaijani public figures to delegitimize Russian peacekeepers, especially in light of the Ukrainian crisis, and calling their presence as temporary, hinting at their expected withdrawal, are premature and disturbing. They do not contribute to the peace and confidence-building process.

Instead, the current peacekeeping architecture should evolve, based on the international norms of peacekeeping. Even if it looks challenging in the current geopolitical environment, few options for a multinational peacekeeping operation under a mandate from an international organization should be considered in order to prevent a relapse into armed conflict and ethnic cleansing, stabilize the security along the line of contact, and contribute to political dialogue, human rights and governance issues in Nagorno-Karabakh:

- The Russian peacekeeping operation should remain to ensure the hard security of Nagorno-Karabakh. At the same time, a mission under the EU Common Security and Defense Policy (CSDP) framework should be deployed to ensure the softer aspects of security. The mission should be one of civil-military or rule of law, without duplicating the Russian peacekeeping mandate and based on the labor division unless it is deployed in the areas where the Russian peacekeepers are not present.

Why would Azerbaijan agree to such a mission? Why would Russia agree to share a peacekeeping mission with the EU? Why would the EU be interested in contributing to the security of Nagorno-Karabakh, and how can Russia and the EU cooperate in a conflict zone when they are themselves on opposite sides in the Ukraine war?

Azerbaijan should be interested in demonstrating the goodwill of its intentions to respect the security and rights of Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh. Additionally, Azerbaijan values its relationship with the EU and there is no legitimate reason it should see an EU Mission in Nagorno-Karabakh as problematic.

Russia may want to share the burden of peacekeeping in Nagorno-Karabakh, especially in light of the ongoing Ukrainian crisis that is stretching its military and economic resources. Russia may also be interested in finding a niche for cooperating with the EU, given its current international isolation.

Some critics point to the Trump administration’s failure in October 2020 to deploy Scandinavian peacekeepers in Nagorno-Karabakh to stop the war as evidence of the EU’s lack of interest to contribute to security in the Southern Caucasus. However, that was a different situation. The deployment of peacekeepers from selected EU countries in the middle of an intensive military offensive in October 2020 and without an organizational umbrella was unrealistic since it would be a peace enforcement operation without preconditions for the peacekeeping. Besides, the EU has a CSDP mission in the Southern Caucasus, namely, it has been operating a EUMM (European Union Monitoring Mission) in Georgia.

The EU has an important role in peacekeeping, conflict prevention and international security. It is an integral part of the EU’s comprehensive approach toward crisis management internationally, drawing on civilian and military assets. Since 2003, the EU has undertaken over 37 civilian or military missions and operations in Europe, Africa and Asia, out of which 18 are still ongoing. In light of the crisis in the OSCE Minsk Group, the EU has taken up the role of a facilitator of a parallel mediation process between Armenia and Azerbaijan, trying to make up for its inaction during the 2020 Artsakh War, to be relevant in the South Caucasus, and to avoid another war in the European neighborhood. Since Nagorno-Karabakh is a small territory, contributing to a peacekeeping there should not require many personnel or involve high costs for European taxpayers. Consequences of a new military escalation will be more costly for the EU than such a stabilizing force not only financially but also geopolitically and reputationally. In the case of another escalation or ethnic cleansing in Nagorno-Karabakh, the EU will face a choice between its geopolitical interests in oil and gas from Azerbaijan, and its value system of the protection of human rights and democracy of Armenians.

Given that both Russia and the EU have been urging the peaceful coexistence of Armenians and Azerbaijanis, they can become a role model for it in Nagorno-Karabakh dividing peacekeeping roles in the territory. Apart from an EU mandate for a CSDP Mission and Statement from November 2020 constituting the basis for the Russian mandate, both missions should receive a mandate from the UN Security Council in the same resolution. The EUMM in Georgia and the Russian troops in South Ossetia have a history of information exchange and cooperation within the Incident Prevention and Response Mechanism (IPRM), and based on that precedent, mechanisms of cooperation can be developed in Nagorno-Karabakh. The war in Ukraine cannot last forever, and at some point Russia and the West will need to cooperate and find common goals and interests. Artsakh can become the beginning for facilitating such cooperation.

2. A reference to a possible OSCE peacekeeping operation was made in several proposals by the OSCE Minsk Group. However, unlike the EU or NATO, it doesn’t have a track record of military-civilian peacekeeping but has had only civilian and monitoring missions. Nagorno-Karabakh was supposed to be a test case for the OSCE but currently the organization is in crisis and lacks consensus on key issues. Establishing an OSCE peacekeeping presence can be a way to revitalize the organization in the presence of political will of the parties concerned; however, it is not probable.

3. Another option could be a UN peacekeeping mission that will combine the Russian peacekeeping contingent and other OSCE member states but be open also to other countries willing to contribute to UN peacekeeping operations in Nagorno-Karabakh. According to the UN procedures of forming a new international peacekeeping mission, countries involved in a conflict cannot be part of peacekeeping forces there. At the same time, parties to the conflict should have decision-making power in defining which countries can contribute to the peacekeeping in the given conflict. In the case of Nagorno-Karabakh, Azerbaijan and the Armenian side, whether it is the authorities of the Republic of Armenia or Nagorno-Karabakh, need to agree on the participation of any state in peacekeeping in Artsakh.

In case of any of those three options, whether an EU, OSCE or UN peace operation is deployed, the peacekeeping architecture should not consist only of a military presence. It should involve an EU, OSCE or UN civilian component as well, independent of the country offices of those organizations in Azerbaijan and Armenia, to deal with political, governance, human rights, protection, humanitarian and development issues. These international organizations should increase their contribution to the peace, security and development in the Southern Caucasus in line with the UN “Leave No One Behind” principle. Nagorno-Karabakh should start receiving international assistance.

4. If the EU or the OSCE are not interested in contributing to security in Nagorno-Karabakh, then it would be important to allocate a UN mandate to Russian military peacekeepers, and to ensure they are complemented by a UN Civilian Office. If an international peacekeeping mission in NK is not established due to a lack of consensus to allocate a mandate or a lack of interest by contributing organizations or countries, the Russian peace support operation should remain there indefinitely. Russia should not, for any reason, withdraw from Nagorno-Karabakh without due warning, or without an alternative arrangement substituting its peacekeeping presence. It should notify about a withdrawal 6-12 months in advance since the deployment of a new international peacekeeping mission and force generation takes approximately one year. Neither Azerbaijan nor the West should advocate for its withdrawal, otherwise hard or soft ethnic cleansing will be inevitable, and it will have high reputational costs for all actors involved – Azerbaijan, Russia, and the West.

Conflict resolution should be sustainable and contribute to positive peace. While the OSCE Minsk Group is currently not operational in light of the polarized geopolitical environment, meditation and negotiations should continue in complementary formats, such as Russian-facilitated working groups, EU-facilitated meetings between Armenia and Azerbaijan, shuttle diplomacy by the U.S., French and Russian Co-chairs of the Minsk Group turned into envoys and acting individually. Negotiations over the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict should continue in order to find a comprehensive and long-term solution for the conflict, address its root causes, provide long-term solutions for all of its aspects and build confidence towards genuine reconciliation and sustainable peace.

Also see

Part I: What May Happen to Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh

In Part 1 of a three-part series, Sossi Tatikyan analyzes the uncertainties and possible scenarios for Nagorno-Karabakh if Armenia’s leadership goes ahead with the recognition of Azerbaijan’s territorial integrity.

Read morePart II: What May Happen to Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh

In order to understand what may happen to Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh if appropriate international guarantees for security and human rights are not put in place for them, Sossi Tatikyan presents the evolution of several comparable conflicts.

Read moreThe Divergent International Approaches to Secessionist Inter-Ethnic Armed Conflicts

The global response to secessionist inter-ethnic conflicts is shaped by a number of factors, from the extent of the threat of ethnic cleansing, to possession and instrumentalization of energy sources and more. Sossi Tatikyan explains.

Read moreNew on EVN Report

The Supremacy of State Interests

Almost all systemic and structural political and military weaknesses of Armenia share a fundamental root cause: the chronic absence of a culture and tradition of Statehood, both in the mindset of the political leadership and the general public.

Read moreThe Imperative to Update Armenia’s National Security Strategy

A new security environment was created after the 2020 Artsakh War, requiring a revision of Armenia’s National Security Strategy that was adopted before Azerbaijan launched the war in Nagorno-Karabakh. Hovsep Kanadyan explains.

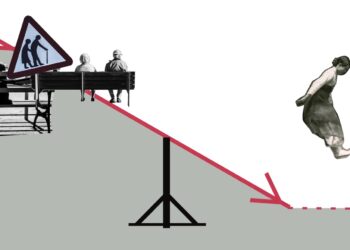

Read moreArmenia in Demographic Crisis

Recent data warns of a demographic crisis in Armenia. In a country with a high rate of aging, programs are being implemented to boost birth rates. But are they effective?

Read moreOpinion

Armenia: What Role to Play in an Increasingly Multipolar World?

Entering the post-Western world, the strategic debate is shifting from a world of alliances toward a world of partnerships. How will Armenia seize this shift of geopolitical tectonic plates?

Read moreCan the EU Influence Baku’s Behavior and What Does This Mean for Their Mediation Efforts?

Instead of making Yerevan step back every time there is a deadlock in the negotiation process, the mediators should instead develop the tools to pressure Baku. If they do not, another war in the South Caucasus is likely.

Read moreWhy Armenia Needs Realpolitik, Now

For over 30 years, there has been a constant refrain on the righteousness of Armenia’s national aims and precious little about the means towards those ends, and the feasibility of those chosen goals.

Read moreArmenia’s “Machiavellian Moment”

The general state of flux and lack of clarity on Artsakh and the negotiation process has produced a great deal of uncertainty, precipitating important questions about nationhood, state-building, and how to move forward.

Read moreArtsakh – Ukraine: Armenia Between Two Wars

In the wake of lingering concern over the events unfolding in Ukraine following Russia’s February 24 invasion and its defeat in Artsakh in 2020, how can Armenia pull itself out of this chain of elevated conflicts?

Read moreSpotlight Karabakh

Despite Everything, Artsakh Celebrates

The resilience to persevere through unspeakable trauma was embodied by the tenacity to celebrate the May 8 and 9 holidays in Artsakh with a full schedule of events.

Read moreAzerbaijan’s Ongoing Policy of Ethnic Cleansing in Nagorno-Karabakh

Azerbaijan’s main goal is the removal of ethnic Armenians from Artsakh through the creation of conditions unfavorable for living, as well as creating an atmosphere of fear among the Armenian population.

Read moreThe Guardian Women of the Front Lines

While the majority of women didn’t pick up guns to fight in the war, many used their skills to fight in their own way. On this first anniversary of the 2020 Artsakh War, Kushane Chobanyan presents the stories of six extraordinary women who were on the front lines.

Read more

What is seriously lacking in this discussion is the empowerment of Azerbaijan by Turkey. Turkey was involved in the planning, managing and bringing in ISIS fighters to Nagorno- Karabakh. Even today, Aliyev does not make a move or a decision without Turkey (Erdogan’s) consent. Turkey is an important country these days, geopolitically. No EU nation nor the US can control Turkey’s expansion plans.