Illustration by Armine Shahbazyan.

Manya Sargsyan

We were preparing for medical exams. It was a chaotic period, at least that’s what we thought at the time. On the night of September 26, I had stayed up late studying and woke up late the next day. I remember opening Facebook and seeing what everyone was writing: War. A few days later I told my family I was leaving and that I would be gone for five or ten days, and for them not to wait for me. I would return as soon as the war ended.

I am a resident in the Department of Pediatric Anesthesiology and I couldn’t even imagine writing my practical exams in the middle of a war. I also work at Surb Astvatsamayr Medical Center as an on-call resuscitator and since our university exam was canceled, I went to work. That day we admitted one of the first boys who was wounded in the war. A drone had hit the road leading to Martakert and from there, he had been transferred to different hospitals and everywhere he was taken, they said he could not be saved. They brought him to us and we saved him…

We arrived in Goris on the evening of October 3. When they saw us there, they were all taken aback by our happy, bright eyes but nonetheless, they were pleased we had gone because they needed extra hands. People at the hospital in Goris were extremely caring. They would bring pickles and jams they had made themselves. It was as if we were home. When we had a free minute, they would set the table and ask us what we wanted. I didn’t know that Goris in the 1990s had been bombed and that the war wasn’t only in Artsakh, but right there, in their own city. It was a revelation to me. And now, it was as if all of Goris was a hospital because all the wounded were brought there straight from the front without receiving medical care elsewhere. I know it might sound uncouth, but there were so many wounded it was as if they were falling on our heads from the sky. The drones could be seen clearly from Goris. There was a balcony where we would stand and watch how our air defense units were shooting down the flying drones.

We would go to Ishkhanadzor regularly with four friends – two doctors, two nurses. A military field hospital had been set up there and I remember how the first time I went it was like a scene out of a movie. There were two or three doctors who were doing everything. Classical medicine went out the window. There was an instance when we were transporting a patient and the bleeding would not stop, there was no other way other than to put your hand in the wound and hold the blood vessel. I still don’t understand how we were able to do it. My organism had mobilized all its resources and pushed me to work without thinking.

You can’t survive a war without humor. Everything is simply so awful that there is no need for additional drama. On the contrary, you want to elevate your own mood, the mood of others. I remember this one time, when we were transporting a patient, a tank was hit about ten meters from us just as I was checking the wounded soldier’s blood pressure. The driver slammed the brakes abruptly; the nurse, the patient and I smashed up against the walls of the ambulance. They were yelling, telling us to get out, I said I still needed to check the blood pressure. I did, and then left the vehicle, but something told me that the soldier’s ventilator had shut off. I checked and it had.

We had decided with my mom to talk once a day. Mornings were relatively calmer so I would call her. My mom was not demanding, she would patiently wait. Months after the war, when the Medical University started publishing the names of the med students who had been killed, it was then that the reality of the situation somehow dawned on my mother. She said, wait, so it was very dangerous, you could have died!

It was hard but we had arrived with light hearts, with a spark typical to the young. However, even that would sometimes not help, there would be situations that were hard to comprehend that they were real. We would always be happy to go, we would go in good spirits, so much so that they would joke about us, they would say Ishkhanadozor was under Manya’s and Lilit’s (my colleague) occupation, they keep bringing in the wounded. There would be unidentified soldiers sometimes, with no information about them whatsoever. In such cases, they would write “unknown soldier” and just put a number on the chart. There was one soldier whose information was unknown, they had given him a number and his chart said Karmir Shuka, table number six. It was very difficult for me, especially because that boy died in Goris, all his internal organs were damaged. There were other deaths as well, but this one really got to me. It was difficult to see the soldiers in the ER, who were lying there naked and all of them had a cross hanging from their necks and no one would touch the cross. It was like witnessing the irony of life, you would be massaging his heart, which often would not restart and you would be looking at the cross hanging from his neck, I don’t know…

Even war has its rules, but this war was without rules. We had a friend who we heard had died during the war but since there was a lot of different information, we refused to believe the news of his death. In December his death was confirmed through a DNA test. That is when I could no longer control my emotions. And you know when else I cried? I think it was on November 5, we had gone to Lachin, we were transporting a soldier who did not have parents. I had given my telephone number to his relatives and we were constantly in touch until we got him to Yerevan. Then they called and told me he had died. And if Manya the doctor could understand the death of the 24-year-old lieutenant, Manya the human gave up. I understood that he was my family, he was only slightly older than my brother, that is how painful it is …

Miracles also happen at war, it would be difficult to go on living without the memory of that miracle. There were soldiers whose hearts we tried to revive for half an hour and we eventually succeeded. Do you know what kind of feeling that is? It is the most gratifying feeling in the world.

The hospital in Goris was operating as normal, also accepting non-war related cases. All the pregnant women from Artsakh had been brought to Goris. I went to watch a birth and still have a recording of that newborn’s first cries in my phone. It is a kind of reminder that parallel to all of this, a new life comes into the world, you see, a child is born, life never stops.

Aznare Bnents

I woke up in the morning and everything was perfect and I was getting ready to go to work at the pub as usual. It was there that I found out that the war had started. For a moment everything got mixed up in my head, I couldn’t understand what was going on, I was trying to convince myself that all will be well. Then I realized that it was self-deceit. The boy I love got drafted the very first day. He went. My brother was a conscript. I thought why would I stay, what do I have to do here? My father took part in the liberation of Shushi and I was thinking, how would I look my father in the eye if I don’t go?

I have a five year old sister. I’m 20 and I have managed to enjoy a lot of things, she hasn’t seen anything yet. Anyway, I registered in the suicide squad, went to the Defense Ministry, applied to many places, but they kept telling me to wait. Then, when I saw that I was not getting a call from anywhere, I decided not to waste time and get to work. There was a Facebook page called, Get in Let’s Go. I posted asking if there was anyone going to Sisian or Goris. A man replied saying he was heading out at 3 in the morning. I went half the way with him then somehow managed to get on a bus. The drivers would say, we are getting men out of Stepanakert, and you are heading there?

I wouldn’t respond, I was simply going to Stepanakert to help. We got there; there was the smell of ammunition in the air. We went to the hospital, the air raid sirens were on. Under the serenade of the sirens, a young guy in a doctor’s uniform was standing by the wall of the hospital. He turned to me and said, “You hear this sound? Remember it, as soon as you hear it, you have to run as fast as you can and take shelter.”

I was thinking, where have I come? What is happening?

With a backpack bigger than my head, I somehow made it to the military hospital. I told them I was a volunteer. They looked at me with my tattoos and piercings as if I was an alien. There was grandma Ella, who came to meet me. Then I saw a priest blessing the soldiers. He looked at me, blessed me too somehow and asked if I believed in God. I said I did. He then told me to clean my hands. He doesn’t know, but I still have my tattoos. They set me up to work in the kitchen of the military hospital. I ended up doing all kinds of things, everything except paint (I’m a painter).

My tattoos were not natural for the employees of the hospital, they used to call me the Yerevantsi mishap. I wanted to confront them, ask them how dare they. I was 20 years old and there to help them, how could they hurt me so relentlessly… Then I started to convince myself that it was probably not about me, that it probably seemed that way to me.

The first day was terrible. They brought in the body of a boy whose face I saw and can never forget. But I overcame that terror. I was there for my friends and for my family, I was not there for the land. Let the land not be there but let the boys be, we can’t bring them back. The first thing I would do is to look at the hands of all the wounded and the dead. Me and the guy I love wear matching rings. I had no communication with my Sako, he did not know that I too had gone to war. We had not spoken since the war had started.

You know, during the war I understood that I was capable of things I would not be able to do during ordinary times; not sleep for days, carry a stretcher, move heavy loads from place to place. People were amazed where I got so much strength from. I slept an hour or two every couple of weeks. I would check in on the wounded at night, feed them, dress them. There were wounded who would not talk because they had seen the death of their friend. I would start working with them and when they finally spoke, I would cry from happiness.

So much of what I witnessed in those days went against all the laws of nature, things that your brain simply cannot comprehend, but there was one incident that really left an impression. They brought in a boy whose leg had to be amputated. He called the girl he loved and told her everything was ok, they had only cut off this leg. The girl told him to never call her again. I was shocked. I called the girl, told her that it was not a joke, they had only amputated one of his legs, she said she was not kidding either and that we should not call again. I wanted to tell her about this other woman, who when she found out that her husband had lost both his legs but was alive, was popping champagne at the hospital out of happiness.

One day, by some miracle, I had wifi. I went on Facebook and saw someone, a common friend of ours, had posted a picture of Sako, and written: My Sako, my friend, eternal light…

I immediately called my friend and he confirmed it; they had brought Sako back that day.

I went down to the cellar, went weak and fell to the ground. I could not understand what was going on. Sako was 22 years old. The next day, on November 4, at around 5 they sent me to Yerevan with the first ambulance. Honestly, the whole way I was begging for it to be a mistake, it could not be him, but I arrived and I saw that it was him. After the funeral something snapped in me and I said to myself, “Aznare, your Sako is no longer but other people’s Sakos still need you.” I went back the same day and decided to do even more for my Sako’s sake, for my brother, but …

It was the 9th, I was exhausted, I was dozing off when one of the boys came and said, “Nare, it’s over, we are going home.”

“What do you mean we’re going home? Is the war over? Did we win?

“The war is over, but we didn’t win, Nare. Sorry, Nare…”

I was standing outside and screaming out of helplessness. I had made a promise after Sako’s funeral that we would do everything to make things better but it got worse. My brother also died. Everytime he called, we would talk. He had called on September 24, asked where I was and had told me to go down to the Opera. I was frazzled, I got dressed, stepped out, and then he was like, “I’m not there yet, but I will come, I will bring flowers…”

Death is not the worst thing that happens at war, the worst is when the war breaks you. It was on the 6th, I remember the day clearly. Dr. Igityan came, stood in the middle of the hospital and said: “If in 1992, we liberated Shushi, today we broke Azerbaijan’s spine in Shushi.”

Everyone was happy, they were hugging, yelling, crying, rejoicing…

On November 9, Dr. Igityan passed right by me in the halls of the hospital, he looked at me, hung his head and walked away.

Shushanik Saribekyan

I was in Germany on September 26, that is where I live and given the COVID restrictions the plan was to stay home. I was watching one of Tsvetana Paskaleva’s interviews and was in awe at how a foreign woman left everything, risked her life and became one with the Armenian land and culture. I do not know if it was providence or something else, but there was a reference in the program to the battles that took place in Karvajar and Getashen. I had an inexplicable feeling but thought it was related to the context of the piece.

I learned about the war just like everyone else, from the news on the Internet. I opened Facebook early in the morning and read that war had started. I immediately called Armenia to confirm if it was true. Unfortunately, the reply was affirmative. My second phone call was to a colleague in Germany who is also a doctor, to let them know that if the war lasts a couple of more days, I plan to go to Armenia to help at one of the frontline hospitals. Their reply was a reassurance that the war will probably not last long; if it was the Turks, then they were probably trying to scare us again. My third call was to a friend in Armenia, I was trying to get more news, I was again told that yes, it was war but there was no need for me, they would call me if there was.

On September 29, when I heard on the news that the enemy’s UAVs had entered Armenian airspace in Vartenis and there were bombings, I definitively decided to go. It was very difficult to get time off in Germany, especially with the COVID-related influx of patients and the shortage of medical staff. So in parallel, I also drew up a plan B, which was to give my resignation if plan A failed. On September 29, I approached my department head and said that there was war in my country and I can’t stay in Germany, I needed to get back and be with my people. I was asked what the situation was, how intense the war was, did I come from the part of the country that was at war? I said no, I did not live there but the whole of Armenia was my home, that I was one of the three million Armenians and could not simply follow the terror from afar. I was asked, wasn’t I worried for myself, after all I was risking my life. I said that was the least of my concerns. After two minutes of contemplation I was told to go and be careful. “If my country was at war, I would do exactly the same thing.”

It is difficult to describe how I felt. We had a serious shortage of medical staff and they still gave me a two week leave even though that was going to be a serious financial burden for the hospital. Something I’m still grateful for. I bought tickets for the earliest flight, but Austrian Airlines canceled the October 4 flight to Yerevan as Armenia was deemed a dangerous conflict zone. Finally I found another ticket and after a 17 hour flight I arrived in Armenia. My mom had come to the airport with my nephew, who was dressed in military fatigues and that is when I felt the war, when it materialized.

I arrived in Armenia at dawn, two hours later I went to the funeral of a school friend who had volunteered to go to the war. I had not seen him since graduation. I applied to the Ministry of Health. I really wanted to go to Artsakh but was told that there are enough doctors there and they sent me to Goris with a group of doctors.

It was my first time going to Goris, more so in an ambulance. The longer we were on the road the more astonished I was with the bravery and self-sacrifice of the young doctors, some of them still med students who were transporting the wounded under shelling. The ambulance had become something of a moving trench and could be targeted by the enemy at any moment. The emergency doctors who were at the front lines, in their own trenches, were waging a battle equal to that of the soldiers

Practicing medicine in a war is an indescribably cruel thing. It is most painful to see an 18-20 year old die for you to live on. I knew I had to do my utmost to save them and when that does happen, the pain is unbearable.

Ina, one of the nurses who worked with me was specialized to assist anesthesiologists. She worked impeccably. When I returned to Germany in December, I learned that Ina’s son was in Jrakan and had been killed there. I often mentally go back and when Ina comes to mind I can hardly understand how a woman, a mother could without a word of complaint, without despair and with such pride deliver medical attention to boys like her son while knowing very well that one day one of them might be her own. Ina has become the symbol of the strong Armenian woman, the strong mother.

One of the soldiers had acute appendicitis. The surgery went well and as he was recovering, I approached him and asked, “Vaghinak jan, tell me what do those mercenaries fighting against us look like?” He looked at me and said, “Doctor jan, have you seen a cow?” I said of course I have. “Well, they are like cows, the more you shoot at them, the more they advance.”

My memories of the war are feelings of sadness and the terror of that war. But I also have one physical momento, it is a picture by 8-year-old Eva from Martuni. She was staying at the same hotel as I. Eva had woken up in the morning from the sounds of explosions and had since clammed up and refused to talk. We had met at the hotel but we did not have verbal communication. One day I told her that if she drew pictures for me I could take them back to Germany with me as memories. She did not say anything but then, two days later she approached me with a bunch of drawings. Now I look at those drawings and regret not having any contact with Eva.

War transforms a person. Somehow you are never the same as before the war. I have a new kind of human appreciation and the only thing I wish for now is peace. The war demonstrated that we need to be much more prepared and united.

*Shushanik is an anesthesiologist and intensive care physician at the Heidelberg University Hospital, Germany

Lucy Hovakimyan

The 26th was a pleasant day. Beautiful autumn weather – neither hot nor cold. We were sitting at a cafe with friends having coffee. What do 20-22 year olds talk about? Mostly girl talk, plans for the future…

I have a small blog on Instagram about healthy lifestyle. I was filming a story for the blog when my father turned the TV on. At first when they said military operations, it didn’t register or we didn’t completely understand what was going on because we’re used to such news. But later it became clear that this was not an ordinary thing.

That morning I saw the announcement by the Health Ministry that volunteers were needed. I signed up without giving it a second thought. Later that evening, we were watching television when the call came: “Are you ready to go to Goris because you filled in the application?” To be honest, when I signed up, I thought that I could help with something in Yerevan. That is, I didn’t fully think through why I had signed up. I asked if I could call them back to have time to discuss it with my parents. My father asked if I was sure I wanted to go. I said, yes, I think I can help. I’ll never forget his reaction. He said, fine, it’s settled then. Get dressed, I’ll take you.

In my backpack, I had put some bananas, masks, and a few first aid items. My backpack and I went to war and the both of us came back heavier than we had been. In the ambulance, there was a nurse, the driver and myself. We didn’t talk of the war, we were simply going to Goris. That’s what we thought but we ended up in Stepanakert. I hadn’t told my family that I was in Stepanakert. In the morning they called and because I hadn’t turned off my GPS they saw that my location said Khankendi. Terrified, they asked where I was, what I was doing. Well, they realized then that I was in Artsakh.

My typical mornings in Yerevan started with breakfast and once in a while, strolls through the streets of Yerevan. In war, mornings begin with war. That morning we woke up at 7 a.m. We thought they would start bringing the soldiers, but no, that’s not what happened. The medical staff there were extremely caring toward us. They were always trying to do something nice for us. Around 11 a.m., they started to bring the soldiers. I had thought that I would go right away to help but instead I stood by a wall, frozen. During your practicum, you don’t see such things. I was looking but I couldn’t comprehend how a human body could be so ruined. I was shocked by the condition of our boys. Then, I quickly composed myself and we transported the wounded to Yerevan.

The next day I went to campus. I did everything I could to digest what had happened, I behaved as if nothing had happened. But then I realized that if I didn’t go back, I would not forgive myself. It seemed kind of simpler and more natural than staying. I went again and did so 20 times.

On October 4, a projectile fell near Stepanakert. Black smoke started rising like a cloud. We all ran to the bunkers and I remember that as I sat down, I almost keeled over, I was incapacitated. I had a classmate who was from Artsakh who came up to me to see if I was fine and said, “This is what it’s like now” and that I had to somehow learn to cope. As soon as the shooting stopped, my nurse, Lilit, who was a very courageous girl said, you are strong, compose yourself. I don’t know how but they managed to find some valerianka for me. I quickly tried to pull myself together because I thought if the soldiers saw me in this condition, what would happen?

During war your life often flashes before your eyes. I came to the realization that I had spent so much time and energy worrying about many insignificant things. Human life, more than ever, became a dominant priority for me. It feels as though I left myself in the war, on those roads…

I had a soldier, an 18-year-old, who had been serving for a month. He had been wounded and we were transporting him to Yerevan. The whole way he was saying that he couldn’t feel his legs. We spoke a lot and in a matter of hours, became friends. When we were nearing Yerevan, I told him we had given him a lot of painkillers, he would have to be patient. I asked him what he wanted to talk about. He said books. I was shocked, like wow. He asked if I had read “Flowers for Algernon”. I said I hadn’t but promised I would. When we got to Yerevan the attending physicians said that in all probability he would never walk again. I was sitting in the lobby of the hospital and was sobbing from my powerlessness. I didn’t know what to do, how to help. I wanted answers, but from whom? A few days later it was my birthday, my nurse gifted me that book and I read it on the road to war.

I went to Stepanakert 20 times to bring back the wounded. On the journeys there I would constantly say that I will have many children. I would joke that I’m going to Yerevan to get married and have children. But that doesn’t mean that the war isn’t a woman’s place. Perhaps I can’t go to the front, or hold a gun but there are many ways to help. If you have to fight for the survival of your homeland, then we all have to go.

***

A few days ago, I called my soldier. No one answered. Perhaps it is better that way because I want to believe from the depths of my soul that he is walking and as long as I don’t speak to him, I can still believe that.

Dilbar Khudanyan

My name is Dilbar but my Armenian friends find it difficult to call me by that name and that’s why they call me Hasmik. I was living a normal life in Armavir when the war started. I am a nurse but right now I am working as a waitress at a restaurant in Hoktemberyan.

For two days, I couldn’t sit still, I knew that I could help in the war. Interestingly, I imagined that my help would not be on the fringes, but in the heart of Artsakh. The next day while I was following the news I saw the message of our Yezidi parliamentarian who was saying that we are going to go and fight in the name of our homeland. I immediately called him and said, “Mr. Bakoyan, I can no longer sit idly by, please, tell me how I can get to Artsakh.” He explained everything and the next day I was at the gathering point for the soldiers. In the meantime, I went to the manager of our restaurant and told him that I am going to war. He looked at me in astonishment, but had known me for a long time, and said, “You are doing the right thing, you should certainly go.” Now, many people come to the restaurant and ask if they can “meet that Yezidi woman who went to war?”

Oh, how I was moved, lost in thought. In our Yezidi culture there are many things that a woman can’t do, never mind a Yezidi woman who has decided to go to war with the men. You should have seen the warmth and respect I received from the boys of the Yezidi detachment named after Kyaram Sloyan…for them, I was their friend, their sister, their mother.

We were going to Artsakh on a road that had always stirred happiness in us. Now it was different. It was raining all the way to Goris. There was no reason to rejoice but we were going with clear minds and pride to protect our land. From Goris they took us to Kubatlu and from there to Jabrayil. The driver said that we had to keep the windows open and constantly look up so that if we saw a drone, we could quickly take cover as we would be targeted by the enemy. I was very scared at that point. You experience unexplainable emotions when you remember your children, your grandchildren, friends…but we somehow managed to reach Jabrayil by encouraging one another. I remember that the rain wouldn’t stop and we were on a rocky road, it was a deserted place and it made the already harsh reality more dramatic.

There were many times that death had come and stood beside me but our boys became stronger before that death. One day, our boys, Tidal, Razmik and a few others, went to the Abovyan detachment that was fairly close to our positions. I don’t remember why they had gone but they had asked me to go with them, but I didn’t. When they were already on their way, horrible shelling began. I cannot describe in words how cruel and inhuman it was. Everyone was screaming, Hide! Hide! I was frozen in shock, I didn’t know what to do, where to hide, where to run. There were two Armenians in our unit. One of them, Edo, came and somehow managed to throw me on the rocks and save me. You know, during war, even ethnicity becomes secondary. One time one of the boys from our unit was looking out toward Jabrayil, that rocky area and innocently asked, “I don’t understand why our Armenians are fighting so hard for this land.” One of our other boys said, “This is our land, whether it’s rocky or green, it is all of ours. A homeland does not have to be beautiful to be loved, we have to make it beautiful.” There was no such thing as an Armenian or Yezidi, at that moment there was an Artsakh and a handful of people who were brave of heart, determined and strong.

When there is a woman in the detachment, the men’s behavior is completely different. They even speak with measured words because you are there. A woman’s presence makes everyone more vigilant. We had a boy, his name was Uso. One day I saw him walking around with a t-shirt and I said, “Ay, Uso jan, wear your clothes, you’ll catch a cold, become sick and that’s all we need right now.” He listened to me, they respected me and would never not do as I asked. I would wrap their wounds, monitor them, and ensure they all ate well. I would make coffee for all of us, we would sing Yezidi songs and inspire one another.

We came back to Yerevan on October 15. A second Yezidi detachment went to replace us. We were going to rest and return. I was weeping the entire way back. The boys thought that something had happened, but in fact, I was feeling somewhat weak. There, in Artsakh, when you are in the middle of a war, you become something like superman. There you are more calm and stronger and for that reason I didn’t want to come back.

When we left Artsakh, there were hairdressers and restaurants in Goris that were open. There was a kind of contradiction. Beyond the mountains, there was a war and on this side of the mountain, life had either stopped or was continuing from the same moment we had left it.

The war gave me a detachment of friends, with whom I lived an entire life, with whom I have passed through death and with whom I would stand beside again if need be.

Anna Hovhannisyan

September in Vanadzor is one of the most beautiful months of the year. On the 27th, we decided to take advantage of the last warm days and go to the forest to decompress a bit. It’s not always that my Facebook newsfeed is active and especially on a Sunday, I didn’t expect to see any news. It was almost noon, when we had already assembled. One of my friends said to check Facebook. I did and saw that the war had started. I was terrified and I immediately called one of my friends, who is a doctor and was already leaving for Stepanakert. I asked what should be done and was told blood donations were needed. I wrote a post on my Facebook page and asked my friends to come together so we could go and donate blood. A few hours later, almost 500 of us, friends and strangers alike, had come together to donate blood. On the 29th I told one of my doctor friends that I would go with them as a volunteer to Stepanakert. I wanted to get to Artsakh as soon as possible and do whatever I could to in some way lighten the burden of people there.

Starting from September 30, I reached out to all possible platforms where women were being recruited and said that I am ready to go to the border. I am a good shooter and had undergone training but if I had waited for my turn to go, the war would have ended. I didn’t wait for it to end. You know, in our Armenian mentality there is an unfounded stereotype that the woman should stay at home, a woman’s place is not at war, but even gender disappears on the battlefield. A woman can shoot well, fight, transport the wounded, can do everything when there is danger. I acknowledge that there are things that only men can do, things that only women can do, but I also know that we have to become one fist and get rid of the limitations we place because of gender. A supernatural power comes over you which helps you do things you normally would not be able to do. War is a heavy thing and there are even men who lose control and that is normal for any human being.

The first time we arrived in Stepanakert and hadn’t even reached the hospital, the air raid sirens went off. We went into the bunker and saw that someone wasn’t feeling well. The doctor asked me to go back up and get his medicine bag from the ambulance. As soon as I reached into the ambulance to pick up the bag, a mortar exploded very close to the vehicle. The bag and the medicines flew from my hands but I didn’t lose my bearings. I quickly picked everything up and as I was returning to the bunker, everything slowed down, just like a movie, and I noticed a rabbit had followed me into the shelter. It stayed with us for a few hours. I don’t know what happened to it later.

There were times that we went to Yerevan from Stepanakert twice a day transporting the wounded to different hospitals. I had never been to Artsakh and how I had dreamed to see that beauty. I have a lot of doctor friends and I had always told them that we would go together so that I could also see Artsakh. When we got there, at that very moment, they brought dozens of wounded soldiers with various injuries. I was leaning against a wall for 20 minutes. To see one wounded is one thing, but that many? Stretchers that were soaked in blood lining the walls…seeing all of that was extremely difficult for me. I had only seen such things in movies. I was only able to grasp what was taking place and come to my senses when the doctor called out for me 20 minutes later.

I saw Artsakh through the blaring ambulance; the uprooted homes, a bombed out Stepanakert bring me no good memories. They had told me that Stepanakert was a very clean city and your heart bleeds when you see it covered in dust and bullets.

In the bunkers, the women are silent. I decided to approach them, talk to them but they would only say come, have something to eat, drink some coffee, but they wouldn’t speak.

When we were transporting the wounded, we would try to keep our spirits up by speaking to one another. We didn’t know whether they were giving us strength or vice versa. There were days that I would go back, crying the whole way, even though I rarely weep. Sometimes my feelings simply overflowed and if they asked me why I was crying, I couldn’t give them a reason. On the road to the war, I remembered that November 2 was my birthday. I wrote on my Facebook page that I didn’t need any gifts, for everyone to donate 1000 drams. In a few minutes, people were transferring funds. In two hours, we raised 1.5 million drams. And the total amount of money transferred to me, including the items that were donated and distributed amounted to 12 million drams

Sadly, the war has not ended for me. I always visit my soldiers, take them money that has been given to me for them. After witnessing those scenes it is difficult to live, but we have to be strong, we have to work harder. We have to start with ourselves, but people at the top must also motivate society.

I have seen the most incredibly brave and courageous boys, brave and unbreakable women and I don’t want to believe that we will not once again rise. We, all of us, just simply have to understand and believe that change begins with each and every one of us.

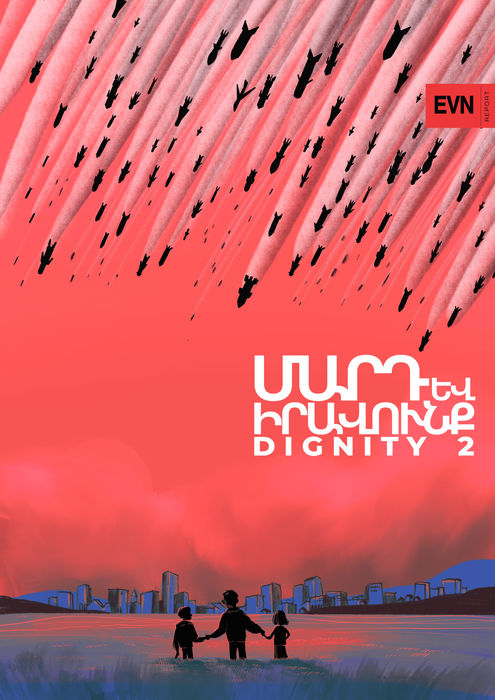

People of War: Living With the Aftershocks

Faced with loss and uncertainty, the Armenians of Artsakh are trying to come to grips with the defeat following the war and finding a way to pick up the pieces of their shattered lives.

Read moreThe Refugees: A Family of Strangers

As the war rages on, almost 80,000 Armenians from Artsakh have fled their native towns and cities and found refuge throughout Armenia proper. While they are grateful for the care they are receiving, their dream is to go back home.

Read moreRemedial Rights in International Law and Their Relevance to Artsakh

In light of the existential threat, high probability of ethnic cleansing and the already imminent humanitarian crisis in Artsakh, the international community has an obligation to grant remedial recognition to Artsakh.

Read more

Azerbaijan’s Anti-Armenian Policies Before the Artsakh War

Although the severity of war crimes committed by Azerbaijan and its disregard for international humanitarian law was unprecedented during the 2020 Artsakh War, it is a continuation of official Baku’s anti-Armenian policy stretching back over a century.

Read moreWar Crimes and Possible Ways to Achieve Justice

Different international courts have jurisdiction over different areas of international law. Ara Khzmalyan explains the avenues available for demanding accountability for the war crimes committed against Artsakh.

Read moreAzerbaijan’s War Crimes

Numerous war crimes were committed during and after the 2020 Artsakh War. This article provides an overview and lists many of the most horrendous and brutal war crimes committed by Azerbaijani military against Armenian servicemen and civilians.

Read moreThe Imperative to Consistently Protect Human Rights

Astghik Karapetyan, the guest editor for this month’s issue titled “Dignity,” writes about the imperative to constantly work to protect the human rights of all, during both times of peace and war.

Read moreLives Undone

In Artsakh, there is a somber air of loss, uncertainty and grief. During 45 days of war, everyone and everything from soldiers to villagers, trees to structures were afflicted and irreversibly altered. A collection of images from November 12-14, a few days after the "peace" agreement.

Read moreThe Responsibility to Protect

The ongoing war in Artsakh has profoundly impacted the Armenian world. Photojournalist Eric Grigorian's photo essay reflects on those who have had to bear the heavy human toll in protecting and safeguarding the homeland. Images are from Artsakh, Goris and Yerevan, taken between October 24 and November 5, 2020.

Read moreA Record of War

Photojournalist Eric Grigorian captures the devastation of war, its destruction of lives, heritage sites and schools. A portrait of a nation at war, of a capital where the elderly and the grieving live underground.

Read moreStepanakert Under Attack

As Stepanakert, the capital of Artsakh came under continual shelling by Azerbaijani armed forces, photojournalist Eric Grigorian captured the devastating aftermath.

Read moreMartakert: A City Fractured

The city of Martakert in Artsakh came under heavy shelling twice since the start of the war. This photo story captures the aftermath.

Read moreStepanakert Shelled

The capital of the Republic of Artsakh was shelled twice today by Azerbaijani armed forces injuring civilians and damaging buildings and infrastructure. Photojournalist Eric Grigorian captured these images in Stepanakert.

Read moreA Home to War

These powerful images capture fragments of life in Artsakh, a place that is boundlessly resilient yet has too often become a home to war.

Read more