“Over the summer my husband and I decided to build a guest house adjacent to our home in Karvachar. On September 26, our friends brought over some construction materials. We were supposed to start the work on September 27, but instead of starting construction, we went into shelters…” Tamara Grigoryan, a 32-year-old resident of Karvachar, recalls the day the 2020 Artsakh War began, revealing the unfulfilled plans and shattered dreams it left behind.

The young couple had moved to the once-liberated homeland immediately after tying the knot. Although Tamara’s husband David was born and raised in Yerevan, he had always thought about living outside the capital city, believing that his knowledge was needed more in other parts of the country. “I myself am from Vanadzor. Before we met, I had attended a lecture about the importance of Karvachar, both strategically and psychologically, and, in general, how important it was to live in liberated Artsakh,” Tamara says. “That idea was always on my mind; however, I never imagined that one day it would be possible to realize it.” In 2012, following their wedding, journalist Tamara and historian David embarked on a journey to follow their dreams.

Once in Karvachar, David started working at the local school, teaching history and social science. In 2017, he began running Karvachar’s Armat Engineering Laboratory. He couldn’t find a specialist to teach computer programming for the students. Although a historian, he decided to learn it himself so that he could teach it, too.

At first, Tamara worked as a journalist, describing life in Karvachar. She soon realized, however, that contributing to the children’s education was where she could make the most impact. She started teaching English and getting involved in implementing non-formal educational programs, including the Wikiclub of Karvachar, which is still active.

When the young couple moved to Karvachar, resettlement plans had already been halted. There weren’t any houses available, so they began to build their own.

“Our friends and others helped us, but there were many difficulties. That is why we were building our house for so long and we had not even finished it yet,” says Tamara.

During the first days of the war, Tamara, like many others, was forced to leave Artsakh. But four days later, she returned, first to Stepanakert, and then once again to Karvachar.

“Of course it was dangerous; however, we did not lose any [military] positions in Karvachar, and the Azerbaijanis did not register any military success,” she says. “Just looking at the strategic position of this area on a map, I was convinced that handing it over would simply be a crime. We were unconcerned about Karvachar; it was impregnable.”

That feeling of invincibility was also shared by Ashkhen Manasyan with regard to Shushi, where she stayed with her young children until the final days of the war.

“Although the capital city of Artsakh is Stepanakert, the heart of Karabakh is Shushi, and I was certain that nothing would happen to my city. When the cathedral of Shushi was hit on October 8, my sister, along with my two children, was there. But even then, we did not leave the city. Moreover, [journalists] came and took pictures of our children, and the entire world got to know my son Arsen,” says Manasyan, 27, whose son is one of the three young children in the well-known photo taken in front of the Holy Savior Ghazanchetsots Church in Shushi.

Her parents are from Stepanakert, but when their house was destroyed during the first Karabakh War, they moved to Shushi, which had already been liberated and is where Ashkhen was born.

Twice Displaced

Her husband’s family was originally from the village of Maragha, which was attacked on April 10, 1992 by a special unit of the Azerbaijani militia. The village was destroyed and residents were massacred.

Although her husband was young at the time, Ashkhen says he remembers how he and his family narrowly escaped the genocide and reached Stepanakert. They then settled in Nor Maragha, which has now been handed over to the Azerbaijanis. The family burned their belongings and left—for a second time. “Essentially, my husband was displaced from Old Maragha, and his children from New Maragha,” says Ashkhen, who has left her most precious possessions in Maragha— the graves of her two children. “In recent years, we moved from Maragha to Shushi, where I worked in the school. If they had not surrendered Shushi, we would not have left it. If we had ever imagined that we would be leaving, I would have at least taken the photos of my two deceased children with me. Instead, we left at the very last minute, without taking anything.” When they escaped to Yerevan, Ashkhen says that they were planning on returning to Shushi the moment the war was over. “We never imagined that one day Shushi would not be ours. Where do I go now? There is no Shushi, no Maragha. My children are buried in Maragha. They destroyed the graves of my children. How can I go live there?”

It is also difficult for Tamara and David to imagine their future in Artsakh.

“All of our relatives would call regularly, urging us to leave, fearing that they will surrender Karvachar too and that it would be too late by then. We would get angry and tell them that they don’t understand the importance of Karvachar, that surrendering it would mean endangering the whole of Armenia,” Tamara says.

On the evening of November 9, after preparing her bread dough, she had gone to bed. At some point during the night, she woke up startled by her husband’s voice. He was talking to someone on the phone and was saying, “It can wait, and we will leave in the morning.” Tamara says she couldn’t comprehend what was going on. “I thought, if Karvachar was captured, then we should leave now, but if not, what in the world could have happened to make David think about leaving,” she says. “I picked up my phone. There were a lot of messages. I did not understand what had happened. Then David said, ‘He has signed it away…’ The mourning that rose up in me was the same mix of emotions and feelings I had when my brother called to tell me that my father had passed…”

A Matter of Hours

In a matter of hours, people had to leave behind everything they had created over a lifetime. They were not even given time to regain their senses following the events.

“We stood with our soldiers until the very last day. However, when we learned that our soldiers would have to leave their positions, we realized that our staying there was meaningless,” Tamara says. “It was not that we were thinking of our own lives. No, our life was in far more danger before that. We simply felt betrayed and sold out. We gathered some necessary valuable belongings and left. Unfortunately, we saw many unpleasant things during those days that we never would have wanted to see; people were looting whatever they could. There were no computers left in the Armat laboratory. They didn’t even wait for people to gather their own belongings. The situation was out of control; there was no police, no state. All this gave me the impression of exhuming a body. Of course, there were numerous honest people that came to save khachkars [cross stones] and assist the local population. However, we saw all sorts of things.”

When asked whether they will return to Artsakh, Tamara responds painfully that, although they imagine their future only in Armenia, they do not have Artsakh anymore.

“When we were in Karvachar, I was certain I was part of the engine of statehood. But now our dream, faith and mission no longer exist. Now I am thinking of at least doing something good, helping somebody. I believe in people, but I no longer believe in the state,” Tamara says. “I do not believe in the Great Idea, which is very painful. David and I experienced the loss of the idea. A house can be built anywhere in the world, but the meaning of it is lost, which is a major, irreversible loss.”

Tamara explains that although the return of the 5+2 regions of Aghdam, Fizuli, Jabrail, Zangelan, Kubatlu, Kelbajar and Lachin, that served as a security buffer, was discussed in all phases of the negotiations following the 1994 ceasefire, nobody believed it would happen.

“Maybe I was very naive, maybe it is my fault that I never anticipated such an outcome, but to give up Karvachar, to give up heights of such importance, an impregnable gateway, with a piece of paper, I could never have imagined it,” says Tamara.

Unresolved Conflict Not a Priority

Resolving the conflict and establishing peace was not always a priority for ordinary citizens, even with regular attacks by sabotage groups and violations of the ceasefire regime throughout the years.

Director of the “Region” Research Center Laura Baghdasaryan says that, up until the 2016 Four Day April War, the attitude of the Armenian public toward the Karabakh conflict was that despite periodic escalations, it was not a priority issue demanding a resolution, or the fact that it was unresolved could seriously endanger and threaten the security of Armenians.

“Surveys were conducted and the issue of the unresolved Karabakh conflict did not occupy the first three positions of potential problems of the population of Armenia. Socio-economic issues, the fight against corruption and so on were considered to be issues of higher priority,” says Baghdasaryan. “After the April 2016 war, of course, the attitude changed dramatically. They started talking more about the unresolved conflict, and the danger of war.” The attitude and perceptions of the people of Artsakh, however, is different according to Baghdasaryan. They have always understood and felt the challenges and dangers of the unresolved nature of the conflict.

Before the March 2020 Artsakh election, the “Region” Research Center conducted a survey among public and political figures. “Expectations were mainly in regards to democratic and socio-economic developments; that is, they singled out issues that were purely civilian by nature. They said that they have been living under conflict conditions for so many years that they have already gotten used to them. Now they consider democratization and development a necessity, so they can talk with the outside world in the same language, so they are in harmony, so that it is emphasized that Karabakh cannot be a part of Azerbaijan, etc. In other words, once again, they linked their development with the conflict,” says Baghdasaryan.

According to research conducted over the years, there was always plenty of chatter about expectations of a large-scale war in Armenia and Artsakh, but the participation of countries other than Azerbaijan was not expected.

“The prevailing stereotype was that a large-scale war was not possible in the region as it would not be beneficial to any superpower, especially Russia. However, it happened anyway,” Baghdasaryan says. “Their calculations for the attack were precise and they launched it when everyone was busy with the pandemic. In Karabakh, they were certain that they would not hand over even an inch of land; that stance had been served to them for a long time, and was in line with the official position. There was no talk of concession and compromise, as the opposing side has never indicated that they were ready for reconciliation. On the contrary, their attitude has become more aggressive and so it is natural that there could not have been profound discourse on compromise by the Armenian side,” says Baghdasaryan.

The issue of the return of refugees has always been a subject of permanent discussion during negotiations. Attempts to reconcile Armenians and Azerbaijanis were realized in the framework of numerous international peace programs, but this large-scale war and the numerous war crimes committed during it—the use of prohibited weapons in peaceful settlements, torture of civilians and prisoners of war, public killings, etc.—nullified the results of those programs and once again proved the impossibility of coexistence, at least at this stage.

“The Karabakh conflict is the only conflict that, firstly, existed for many years without any communication between the parties, and secondly, even with such intensity, there were no peacekeepers. Yet now, the Russians have arrived, along with a Russian-Turkish monitoring center. These days, we are already hearing news of terrorist attacks. If Aliyev had wanted coexistence, he should have been working on it for years. From an early age, Azerbaijanis are raised with hatred, and now they torture prisoners of war and rejoice. I regret to say that we will yet be seeing many acts of provocation,” says Baghdasaryan.

Tamara also does not envision the coexistence of Armenians and Azerbaijanis at this time.

“We have never had that kind of hatred, malice, enmity towards the enemy, but it is the opposite with Azerbaijanis,” she says. “So many atrocities took place during this war and the already existing hatred has intensified so much that they have left no room for coexistence. This is also a matter of dignity. When your opponent does not understand you in any way and does not want to concede anything, why should we give in all the time?”

However, Tamara is certain in one thing: even after all of this, one should not become bitter.

“By becoming bitter, first of all we harm ourselves. I am sure that we have another value system that can make us even stronger. I am certain that children should receive good quality education, become strong and independent people, know the history and especially its shameful pages. Even after the night of the bombings, we did translations in the morning. These days too, we work with children and we do translations. As it is, the children have already lost time, and we cannot afford to lose more time.”

Education Is the Future

The vice principal of Stepanakert’s High School N.11, biologist Geghanush Gyagunts, also sees the future in education. After the ceasefire was established, she was the first to rush to her beloved school, trying to put it in order with her colleagues and to prepare for classes.

“The windows of the old school building are broken. Our neighboring school is completely destroyed; the students will probably be transferred to our school. At the moment, it is us women gathered together, clearing up, until the men are able to leave their military posts,” Geghanush explains. “We have about 500 students, most of whom have already returned. We were constantly in touch with the children, conducting online, distance classes. Our older high school pupils were registered as volunteers and helped in every possible way. Yesterday, they came to school to help us. There is no need to tell them anything; they already know what to do and how to do it. One of my students says, ‘I used to always say homeland, but I did not feel or imagine that I could appreciate the significance of my homeland to this extent…’ Our children have grown up overnight,” says the teacher.

Geghanush believes there are difficult days ahead for teachers, especially in the near future.

“War has its written and unwritten rules. Everything happens during a war; however, this was completely different—more painful and with many more victims,” she says. “We have many victims among our students, the school’s military leader has died, a majority of the teachers have lost relatives, lost their homes, and some of our students are prisoners of war. We had strong boys who are now prisoners of war. This is indescribable. The pain has overwhelmed everyone, but life seems to be trying to go on. Today, after returning to the town, children first ran to school with smiles. You can’t help but be happy. We smile in front of them, then turn around and weep. We must be strong; we must educate a worthy generation.”

Geghanush also believes that it is time for everyone to think about the mistakes that have been made. “Our materialism brought us to this day,” she says. “If one less stone had been used to build mansions and a bullet purchased instead, maybe the picture would have been different. Unfortunately, we are greedy.”

Geghanush was born and raised in Yerevan. She graduated from Yerevan State University’s faculty of biology and was a lecturer there. However, following the first war, her parents decided to live in Artsakh in 1995, returning to where their parents had settled after escaping the 1915 genocide. Geghanush couldn’t leave her elderly parents alone, and so she moved to Artsakh with them. Since then, she has been working at the school.

“When everything was better, I had one foot in Armenia and the other in Artsakh. But now, I don’t even consider leaving Artsakh,” she says. “Before this, I was considering returning to my Yerevan apartment for a period of time, to be carefree and unburdened. But now, if we let such ideas cross our mind, we are committing a sin before these boys. Some of the boys were describing that when dying friends would ask ‘What happened?’ they would only respond with ‘we won,’ so they could close their eyes in peace… This is the nation’s sorrow, its tragedy. And for this very reason, we must live; we must keep the memory of these boys alive,” says Geghanush.

Alina Vardanyan, who lived in the village of Aghavnatun in the region of Kashatagh, jokes, “Who knows? By now the Turks are probably crammed in my cellar and are liberally eating all my preserves intended for the winter.” She tries to put on a brave face in front of the children to ease their sorrow. Her eyes, however, betray her. “At first, I cried a lot. But can I change anything by crying? I only hurt my children more.”

Alina, 35, is from the Jrapi community in the region of Shirak. Her family settled in the Vurgavan community of the Kashatagh region through the resettlement program of the late 1990s. Later, she got married and moved to Aghavnatun. Now both communities are under Azerbaijani control.

Her husband, brother and brother-in-law were on the front lines when Alina, a mother of three, and other women were forced to leave Artsakh on September 29, to protect their children. They were hosted in the Aghajanyan camp of the Armenian Catholic Church in the Torosgyugh community in Armenia’s Shirak region.

“We never thought that we would have to leave these lands. We never would have believed that we would follow the same path as our ancestors. I never would have thought that, one day, we would lose everything like this,” Alina says. “However, we can restore everything, even our lost homes, but we will never be able to bring back the many innocent victims.”

She hopes that the presence of the Russian peacekeepers will keep the sides vigilant and ensure security.

“The Russians also guard the border with Turkey in Jrapi. We have never had a problem with either the border guards or the border. I think they will safeguard the border of Artsakh in the same manner. I am sure that Turkey and Azerbaijan will not take any action against Russia, whereas they are not afraid of us,” says Alina.

She is infinitely optimistic and does not lose hope. She says she will not stay in Armenia. She is ready to live wherever, as long as it is in Artsakh.

“My five-year-old son asks me why we didn’t win. I tell him that, as long as we haven’t accepted our defeat, we have won. I don’t accept my defeat and am waiting for when my husband calls on me to return to Artsakh,” Alina says. “As long as there is a house, I will take my kids and leave right now, doesn’t matter where or what. Both my mother and sister want to return. You preserve and flourish the land by living on it. If all of us get up and leave, then how will the country continue to exist?”

also see

Despair, Anger or Resolve

Resolve is different from blind faith that “this too shall pass.” We need the entire Armenian nation to start getting ready for the next encounter, writes Raffi Kassarjian.

Read moreThe 2020 Artsakh War: One Stepanakert Family’s Story

Statistics about numbers of civilians and young conscripts killed in conflict often water down the true magnitude of human loss. This is the story of one family’s struggle through the 2020 Artsakh War.

Read moreFailure to Prevent and Protect

In Stepanakert, EVN Report spoke with Artsakh's Ombudsman Artak Beglaryan about the political decisions of the international community and the reasons for the artificial parity in their vocabulary, their failure to realize that authoritarian regimes do not understand the language of statements but that of action and their failure to prevent, followed by their failure to protect.

Read moreThe UN, International Organizations and States Are Obligated to Provide Humanitarian Aid to Nagorno Karabakh: Here Is Why

The humanitarian emergency in the Republic of Nagorno Karabakh requires the engagement of humanitarian and donor organizations, without regard to its international recognition, its present or future status.

Read moreThe Women of Artsakh: Our Children Are Being Deprived of the Right to Life

Fleeing the war, the women of Artsakh -- mothers, daughters, sisters and wives -- held a rally in front of the UN building in Yerevan asking for one simple thing, the right to live in peace.

Read morephoto stories

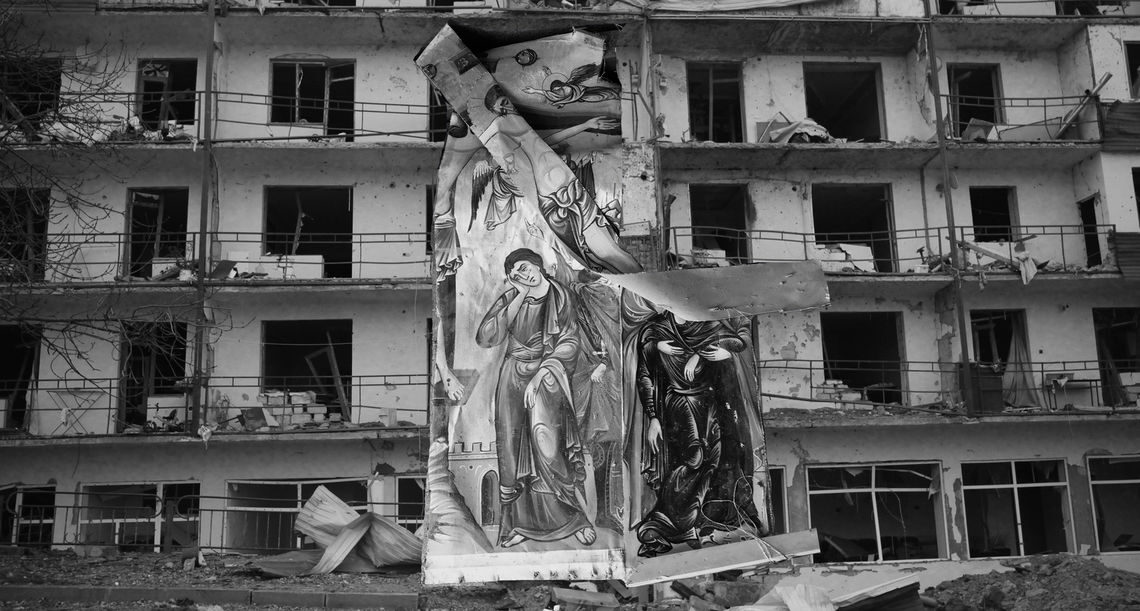

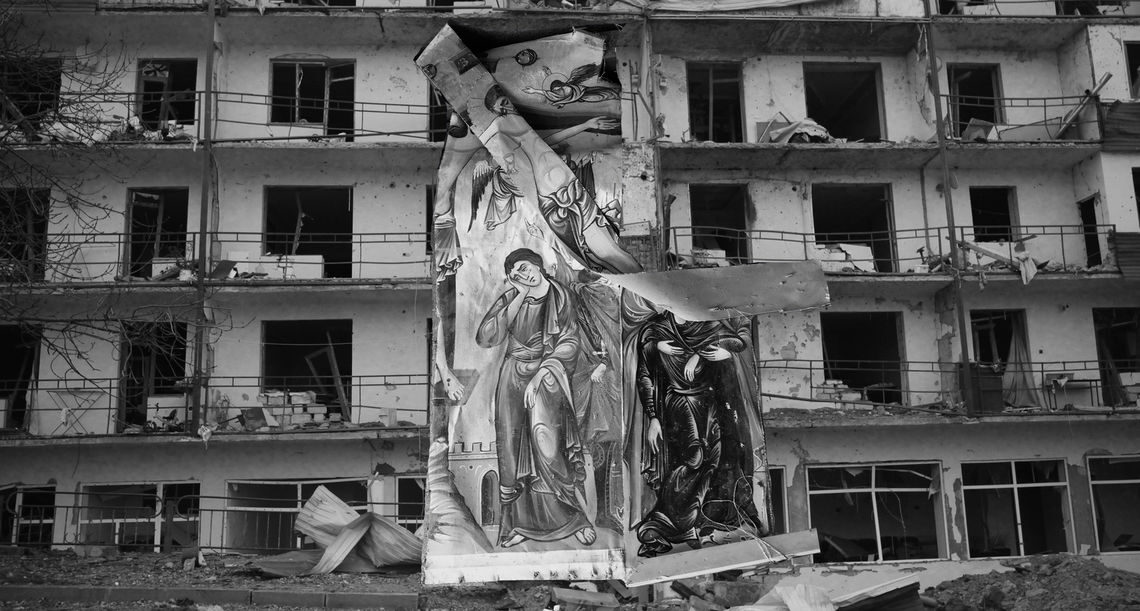

Lives Undone

In Artsakh, there is a somber air of loss, uncertainty and grief. During 45 days of war, everyone and everything from soldiers to villagers, trees to structures were afflicted and irreversibly altered. A collection of images from November 12-14, a few days after the "peace" agreement.

Read moreA Record of War

Photojournalist Eric Grigorian captures the devastation of war, its destruction of lives, heritage sites and schools. A portrait of a nation at war, of a capital where the elderly and the grieving live underground.

Read moreStepanakert Under Attack

As Stepanakert, the capital of Artsakh came under continual shelling by Azerbaijani armed forces, photojournalist Eric Grigorian captured the devastating aftermath.

Read more