Azerbaijan’s recent aggressive policies have been under-discussed in terms of their legal justifications and consequences. While the international community has condemned these actions, the legal aspects of Azerbaijan’s use of force require closer examination. This article unequivocally asserts that Azerbaijan’s use of force is incompatible with the prohibition on the use of force under the UN Charter. Furthermore, Article 51 of the Charter, providing a robust exception to the prohibition, does not validate Azerbaijan’s actions in any way.

Against the aggressive foreign policy that Azerbaijan’s President Aliyev has been preaching and practicing for a while, my focus is on a critical question: Did Azerbaijan’s use of force in September 2020 and 2023 adhere to the principles of international law?

The Bedrock of Peace

It all begins and ultimately revolves around Article 2(4) of the UN Charter, which encapsulates the primary rule on the prohibition on the use of force. This provision reflects a fundamental rule for the maintenance of international peace and security. Another pivotal principle is enshrined in Article 2(3) of the Charter, mandating that all member states shall resolve their international disputes through peaceful means.

The commitment to peaceful dispute resolution finds reinforcement in the 1970 UN General Assembly Declaration on Friendly Relations, where Principle 1 firmly underscores that states must abstain from the use of force in settling their international disputes, including matters related to state boundaries and international demarcation lines, such as ceasefire boundaries. This is a customary principle that applies regardless of whether a state possesses a legitimate title over the disputed land.

You Can’t Call It Self-defense

Central to this article are the conflicting views held by Azerbaijan and Armenia regarding the legal status of Nagorno-Karabakh (Artsakh). While Azerbaijan has consistently claimed the territory as its own, Armenia has championed Nagorno-Karabakh’s (external) self-determination. This fundamental disagreement has led to a legal dispute over the territory between the two nations. From a legal standpoint, the armed conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh has always been classified as an international armed conflict involving Azerbaijan and Armenia. However, it’s important to emphasize that current international law, particularly the framework for international peace and security outlined in the UN Charter, unequivocally prohibits the use of force as a means to settle disputes between states. While valid criticisms exist regarding the effectiveness of this system, exploring that topic in depth is beyond the scope of this article.

In this context, the Mavrommatis case, involving Great Britain and Greece, is a relevant example. The Permanent Court of International Justice (PCIJ) in that case stated that:

“A dispute is a disagreement on a point of law or fact, a conflict of legal views or of interests between two persons.”

This definition helps elucidate the concept of a dispute, including a legal one, and its application can be seen in various contexts, including the one between Azerbaijan and Armenia over Nagorno-Karabakh since the early 1990s. The issue has never been referred to the ICJ, which could have significantly enhanced the legal discourse. The primary and only pathway to resolve this dispute has consistently been through peaceful negotiations. This principle follows from Article 2(3) of the UN Charter. The negotiations between Azerbaijan and Armenia were facilitated by the OSCE Minsk Group, which mediated the Prague Negotiation Process.

With this understanding, the following key points emerge:

- A dispute has unequivocally existed over the status of Nagorno-Karabakh between Azerbaijan and Armenia.

- This dispute has been an integral aspect of the international relations involving these two nations.

Given this foundation, both Azerbaijan and Armenia have consistently been bound by the obligation to seek peaceful resolutions for their disputes under international law.

Since international law prohibits the use of force to resolve disputes between the states, Azerbaijan’s use of force could only be justified under limited grounds, given that the prohibition on the use of force under the Charter is not absolute. Two critical pathways allow states to employ force:

- Upon an authorization from the Security Council under Chapter VII of the UN Charter.

- Exercising the right of self-defense under Article 51 of the Charter.

To assess the legality of Azerbaijan’s use of force, we must explore whether a prolonged occupation grants the aggrieved state the right to self-defense. In this context, I consider the situation in Nagorno-Karabakh as a belligerent occupation by Armenia under Article 42 of the Hague Regulations of 1907 (see here, para 186). Controversial as this viewpoint is in Armenia, this does not necessarily affect the separate questions of Nagorno-Karabakh’s declaration of independence and the right to external self-determination. These inquiries, although of great significance, lie beyond the current scope of this piece.

The use of force is inherently context-specific, and its implications become clearer when examined within specific situations. Take, for instance, the situation where Azerbaijan occupies and claims over 150 square km of Armenian territory. Does this entitle Armenia to use force to reclaim the territory? The legal response to this question is a deductive one: the use of force is categorically prohibited, except when authorized by the UN Security Council under Chapter VII or in cases of self-defense as per Article 51 of the Charter.

In the absence of authorization from the UN Security Council to employ force, the only conceivable avenue that could potentially justify Azerbaijan’s use of force would be the right to self-defense. Article 51 is a specific provision that can be invoked solely “if an armed attack occurs.” Its primary objective is to repel or reverse such an attack, and it does not extend to broader purposes. Furthermore, the right to exercise self-defense lasts only until the Security Council has taken the measures necessary to maintain international peace and security.

The crux of the matter lies in whether any occupation resulting from an unlawful armed attack qualifies as a “continuing” armed attack — a sine qua non requirement for the emergence of the exercise of self-defense. In the context of Azerbaijan’s use of force in 2020, scholarly opinions diverge on this point, with one school of thought affirming it (as seen here and here) and the other challenging it (see demonstrated here and here). I argue that Azerbaijan’s use of force was illegal, given that its right to use force had been diminished after the 1994 Bishkek agreement. In the case of the Nagorno-Karabakh dispute, the international community, particularly led by the United States, Russia, and France, has engaged in extensive mediation efforts, yielding various principles and roadmaps. This can be construed as diminishing the immediacy of self-defense following an armed attack.

Indeed, the language of Article 51, particularly the phrase “if an armed attack occurs,” implies a rather instantaneous event or a series of events transpiring at a particular moment in time. It refers to the initial invasion or attack that leads to occupation, rather than a prolonged state characterized by the absence of active hostilities. To equate occupation with a “continued attack” that would justify recourse to self-defense is against the grain of the Charter’s intent. Any such interpretation would pose a significant challenge to the overarching framework designed to preserve international peace and security.

Notably, Azerbaijan did not explicitly invoke self-defense against the status quo in Nagorno-Karabakh. Instead, Azerbaijan alleged that Armenian Armed Forces had committed “large-scale provocations” and subjected the entire length of the contact line to “ intensive shelling” prior to its “counter-offensive”. In the eyes of the international community, there was hardly any doubt regarding the sequence of events and who initiated the hostilities. President Aliyev himself consistently emphasized this perspective, underlining the broader context within which the hostilities unfolded (see here and here). Furthermore, the joint condemnation by Russia, France, and the U.S. does not align with the notion that an occupied state is free to unilaterally challenge the established status quo through military means.

The Fork in the Road

Peaceful negotiations have consistently been the only viable approach, without the option of unilateral decisions by Azerbaijan to resort to force when it deems negotiations fruitless. International law unequivocally prohibits states from keeping an “ace up their sleeve” in the form of violence. Negotiations were not meant to serve justice to Azerbaijan but to find a mutually acceptable resolution, which is their inherent purpose. As a matter of fact, Azerbaijan, along with Armenia, has played its part in the failures of the negotiation process. Although, despite more than three decades of negotiations, sensible progress has remained elusive, with both parties placing blame on each other for the protracted stalemate, this lack of progress does not grant Azerbaijan the right to impose its position by force.

Notably, in 1993, the United Nations Security Council adopted four resolutions regarding the conflict, which urged all involved parties to halt armed activities, enforce ceasefire agreements effectively, and persist in seeking a “negotiated settlement of the conflict.” These resolutions explicitly excluded the use of force as a viable and lawful means of resolving the dispute. These measures constituted the Security Council’s efforts aimed at restoring international peace and security for the purposes of Article 51. This fosters the notion that Azerbaijan’s right to self-defense ceased following these resolutions and the subsequent Bishkek ceasefire agreement in 1994.

Countering Aggression… or Fueling It?

Considering the combined implications of the immediacy requirement for legitimate self-defense stipulated in Article 51 of the Charter and the overarching principle prohibiting the use of force to resolve territorial disputes, it becomes evident that Azerbaijan’s use of force violated the fundamental principle of non-use of force. This effectively categorizes Azerbaijan as an aggressor.

So, what happens next? The prohibition against the threat or use of force stands as a peremptory norm, an imperative and non-negotiable standard within the international legal framework. Consequently, common sense calls for sanctions in response to international wrongs. Yet, international law lacks the executive and punitive mechanisms that are commonly found in national legal systems. Instead, the responsibility for upholding and enforcing international law largely falls upon the states themselves.

Indeed, in the Nicaragua and Armed Activities judgments, the International Court of Justice acknowledged that a breach of the “principle of the non-use of force”, under the law of state responsibility for internationally wrongful acts, carries the obligation for the offending state to provide reparation to the victim state. Chapter III of the International Law Commission Articles on Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts (2001), (ARSIWA) places a significant emphasis on the role of third states as guardians of community interests, including the paramount interest of upholding global peace and security.

Even in an ideal world where the international rule of law prevails over political considerations, any attempt by Armenia or other interested states to seek reparations for injury would likely encounter Azerbaijan’s counterclaims of alleged prior breaches on Armenia’s part. Instead, economic sanctions against Azerbaijan seem to align more seamlessly with established state practice.

The “Counterterrorism” Opera

When it comes to Azerbaijan’s so-called “anti-terror” operation in Nagorno-Karabakh, which commenced on September 19, not only was this use of force unlawful, but it also raised international humanitarian law (IHL) concerns. Azerbaijan’s characterization of its operation as “counterterrorism” appears to be a strategic move aimed at leveraging a law-enforcement paradigm, which provides a broader range of coercive tools compared to the framework governed by IHL. However, the proper legal framework applicable to Azerbaijan’s operations should be determined by the specific circumstances on the ground.

The Shadow of State Terrorism

Since Azerbaijan lacked effective control over the region at the time of the attack, IHL remains the applicable legal framework for assessing the situation (see here, para. 832). Therefore, there are compelling reasons to classify Azerbaijan’s operations as containing terrorist acts during armed conflicts under international customary law.

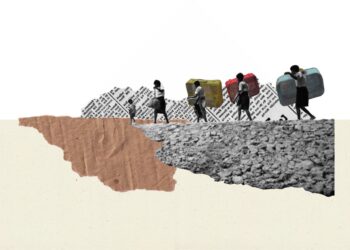

While international law does not offer a comprehensive legal definition of terrorism, the legal community has adopted a sectoral approach to address various aspects of terrorism and its implications (see here, here, here, and here). The customary rule governing the conduct of hostilities explicitly prohibits acts or threats of violence whose primary purpose is to spread terror among the civilian population. Analyzing Azerbaijan’s indiscriminate attack from September 19-21, it is evident that the primary purpose can be inferred from the outcomes of these operations. The shelling resulted in the terrorization of the local population, prompting them to flee their homes seeking refuge in Armenia. As of the time of this writing, over 100,000 forcibly displaced Armenians, undergoing yet another humanitarian crisis, seek shelter in Armenia.

Azerbaijan’s establishment of control over Nagorno-Karabakh was achieved through a strategy of ethnic cleansing. Paradoxically, Azerbaijan’s “anti-terror” operation constitutes arguably a textbook example of acts of terror under Hague law – rules restricting methods and means of warfare. The egregious actions committed by Azerbaijani political leaders and military personnel fall squarely within the purview of international criminal law. This includes a range of serious offenses such as war crimes, including that of terrorism, crimes against humanity, genocide, and crimes of aggression. Armenia’s recent ratification of the Rome Statute, the treaty establishing the International Criminal Court (ICC) paves the way for more effective personal criminal accountability for the culprits. While the ICC does not have explicit jurisdiction over the international crime of terrorism, acts of terror can theoretically be classified as war crimes or as one or more of the prohibited acts within the definition of crimes against humanity. However, it is regrettable that only acts allegedly committed on internationally recognized Armenian soil (not in Nagorno-Karabakh) fall under the jurisdiction of the ICC due to Azerbaijan’s non-acceding to the Rome Statute.

Nonetheless, national legal systems have “universal jurisdiction” over serious international crimes, such as war crimes, crimes against humanity, genocide and torture, allowing them to prosecute these crimes regardless of where they were committed. While this approach can be problematic in practice, it provides a valid means to prosecute alleged perpetrators.

The stark reality of aggression, including prima facie acts of terrorism, demands resolute action and accountability. Azerbaijan, emboldened by impunity, is aggressively pursuing irredentist foreign policies, now targeting Armenia proper. Armenia must swiftly transcend the shadows of its own grave missteps, and among other imperative measures adopt a robust and unequivocal legal strategy to safeguard its sovereignty and deter further acts of aggression. This strategy should make full use of the array of tools and international legal platforms at its disposal.

Also see

Ratified, Unsatisfied: Addressing Ongoing Concerns About Armenia Joining the ICC

While some welcomed Armenia’s ratification of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, a cohort of skeptics remain opposed to the idea. Sheila Paylan addresses the most relevant concerns.

Read moreAn Uncertain Future, Uncertain Status

Over 100,000 forcibly displaced Armenians of Artsakh are now in Armenia facing the crippling challenge of starting over after losing everything. They also face an uncertain future with regard to their status.

Read moreThe EUMA After the Fall of Artsakh

With the collapse of Artsakh, will the EU further enable Baku’s irredentist agenda to seize Armenian territory as part of the opening of the “Zangezur Corridor” or will Brussels show the same initiative to sanction and deter Azerbaijan that it deployed in response to Russia’s aggression in Ukraine?

Read moreCan the International Community Reverse the Ethnic Cleansing of Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh? Part 1

The collapse of Artsakh is the failure of preventive diplomacy, the end of the human-rights-based liberal world governance system and can embolden other autocratic states to use force against small entities claiming self-determination to subjugate or eliminate them in other parts of the world.

Read moreWhat Happened to the Promise of Leaving No One Behind?

Despite unequivocal evidence, the United Nations, like other international actors, failed to address the threats looming over the Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh, who today are uprooted, homeless, forcibly displaced with thousands more still fleeing.

Read moreCSTO: Closer to Azerbaijan Than Armenia, Part II

The question of whether Armenia should remain a member of the Russian-led Collective Security Treaty Organization or withdraw continues to be debated in Armenian political circles. Armine Margaryan explains and offers a new perspective.

Read moreFrom Sri Lanka to Artsakh: Human Stories of Blockade

If they had survived it, and done so with grace and empathy, then what is to prevent us from doing the same, writes Shoushan Keshishian, about Vasuki, a survivor of the blockade of Jaffna, Sri Lanka.

Read moreAutocratic Legalism and Azerbaijan’s Abuse of Territorial Integrity

Azerbaijan’s approach to the Nagorno-Karabakh issue is a perversion of the concept of territorial integrity. It makes a mockery of legalism and constitutionalism, hijacking the law and using it extra-legally to violate civil, civic and human rights.

Read more