On October 3, 2023, an overwhelming majority of the Armenian Parliament voted in favor of passing a bill to ratify the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC). The President of Armenia has 21 days to sign the bill (see Armenian Constitution, Article 129), after which Armenia must deposit the instrument of ratification with the Secretary-General of the United Nations for the Statute to enter into force for Armenia 60 days later (see Rome Statute, Articles 125-126). Once these final procedural t’s are crossed, Armenia will then become the 124th member state of the ICC.

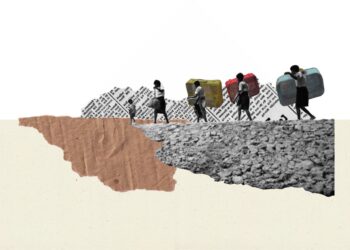

Parliament’s move was met with jubilation by many in Armenia. After nearly two weeks of watching the horror of Azerbaijan’s success in ethnically cleansing Nagorno-Karabakh of its indigenous Armenian population unfold, and enduring more than two years of mounting Azerbaijani aggression and war crimes in Armenia, the resounding yes towards finally ensuring a viable avenue to hold perpetrators criminally responsible for atrocities against Armenians provided much welcome respite.

A cohort of skeptics, however, still remain opposed to the idea of joining the ICC, despite the several advantages of doing so having been fleshed out in different platforms already (see e.g. here, here and here). For the sake of avoiding repetition, this article will not reiterate the pros but rather focus on addressing the most relevant perceived cons.

Fear of Russian Backlash

This fear ties mainly back to the fact that the ICC has issued a warrant for Russian President Putin’s arrest at roughly the same time as Armenia’s constitutional impediment towards ratification was lifted. All member states of the ICC have an obligation to cooperate with the ICC (see Rome Statute, Article 86 et seq.), including with the execution of arrest warrants, which means that Armenia would normally have to arrest Putin if he ever set foot back on Armenian territory. This concern was preliminarily addressed in a previous article for EVN Report, showing that the law regarding immunity for Heads of State implies that Armenia (among all other member states) could arguably be exempt under Article 98(1) of the Rome Statute from necessarily having to execute the ICC’s warrant against Putin.

In this respect, Armenia has also offered Russia a bilateral agreement under Article 98(2) of the Rome Statute since April to dispel any remaining concerns as to Armenia’s moving forward with the ratification process, but these efforts have yet to be accepted by Russian counterparts. Whether or not Russia accepts the offer doesn’t change the fact that Armenia could not reasonably or realistically be expected, including by the ICC, to single-handedly execute an arrest warrant against the sitting head of a nuclear state unless it were expected to embark on a suicide mission. Stronger countries have refused to execute such warrants in respect of less powerful heads of states, as in the case of former Sudanese President Omar Al-Bashir. The classic proverb by Saint Thomas Aquinas “nullus tenetur ad impossibile” (no one can be held to the impossible) is thus very much applicable in the case of Armenia arresting Putin. And everyone, including Russia, knows that.

In this light, Russia’s discontent cannot derive so much from any serious concerns of arrest but rather from mere annoyance that Armenia might dare to start standing on its own two feet. And to threaten Armenia with retaliation for this is completely unacceptable. Armenia has made it clear time and again that its decision to join the ICC has nothing to do with Russia and everything to do with Azerbaijan. And Russia’s inability or unwillingness to honor its military alliance with Armenia and its promise to protect the Armenians of Artsakh have left Armenia with no other choice but to seek alternative measures for accountability and deterrence elsewhere.

Doubts of Deterrent Effect Against Future Azerbaijani Crimes

The easy answer here is that, if we don’t ratify the Rome Statute to join the ICC, we can be 100% certain that it will have no deterrent effect against the commission of future atrocity crimes on Armenian territory. Entire criminal justice systems around the world are based on the theory of deterrence. And research shows that the chance of being caught has a powerful deterrent effect.

The fact that Azerbaijan is not a member state of the ICC does not preclude its nationals from prosecution if they commit crimes under the Statute on Armenian territory once Armenia becomes a member state. One may still understandably doubt whether Armenia’s ratification of the Rome Statute will have any deterrent effect on someone like Azerbaijani President Aliyev, but even that is surely to change now with the ICC’s issuance of an arrest warrant against Putin.

There are, however, countless other potential Azerbaijani perpetrators of war crimes – soldiers, commanders, members of Aliyev’s regime, etc – who do not benefit from any immunity and will think twice before engaging in actions that could be considered as international crimes. The summary execution by Azerbaijani soldiers of at least six unarmed Armenian soldiers near Sev Lich last year is a perfect example of a crime that is far less likely to occur once perpetrators become exposed to the real possibility of pursuit and prosecution by a body such as the ICC.

Criticism That Armenia Is Giving Away its Judicial Sovereignty

No, that’s wrong. The ICC operates on the complementarity principle, which means that it can only exercise jurisdiction when national courts are unable or unwilling to prosecute individuals for the crimes within the ICC’s jurisdiction. This principle upholds the sovereignty of states by allowing them to handle cases domestically whenever possible. The ICC only has jurisdiction over a limited set of crimes and only applies to cases involving the most serious international crimes. It does not have the authority to interfere in other aspects of a country’s legal system. States that are party to the Rome Statute thus maintain control over their domestic legal systems. They can investigate and prosecute crimes within their jurisdiction, and only if they fail to do so, or if their efforts are deemed insufficient, would the ICC potentially step in. As such, the ICC does not usurp Armenia’s judicial sovereignty but rather supplements it.

Concerns That Armenians Might Be Investigated or Prosecuted

The ICC’s jurisdiction extends over Armenia’s territory as well as its nationals. So yes, when Armenia becomes a member of the ICC, Armenian citizens could potentially be investigated and prosecuted by the ICC for crimes within its jurisdiction. It bears reiterating here though that the principle of complementarity still applies: if an Armenian national commits such crimes and Armenia’s domestic legal system is able and willing to properly investigate and prosecute them, the ICC will not intervene. But none of this should be a problem so long as Armenians don’t commit such crimes. Anyone who commits atrocity crimes, whether Azerbaijani or Armenian or otherwise, should be prosecuted and punished.

Conclusion

This article does not pretend to provide absolute certainty that Armenia’s ratification of the Rome Statute will abound solely with benefits without any possibility of risks. That being said, being too risk averse only holds us back and there is no denying that Armenia’s decision to join the ICC despite so much pressure not to by Russia has been bold and brave. It is a move that the Armenian nation can be extremely proud of and has been abundantly praised by like-minded members of the international community. Even Ukraine, with all the support in the world including from the ICC, has not taken the step of ratifying the Rome Statute. That’s not a great look for Ukraine and has not gone unnoticed.

We are finally showing our sovereign will and strength, against enormous odds, as well as our commitment to international peace and security. We are showing those who will try to bully or transgress against us that we are not guided by fear but by our collective empowerment. And to anyone who thinks there’s no reason to do this, all I can say is that then there is no reason not to, especially if we could stand to gain so much out of it: justice, reparations, and deterrence – everything we never got after the Armenian Genocide – as well as enhanced autonomy and standing in the international community.

And like any party that doesn’t quite turn out as fun as hoped, if we end up really disappointed with having joined the ICC, we can always leave (see Rome Statute, Article 127). Burundi did it. So did the Philippines. Again, not a great look, but it’s always an option. First though, we at least have to give it a try.

Also see

Recent articles

An Uncertain Future, Uncertain Status

Over 100,000 forcibly displaced Armenians of Artsakh are now in Armenia facing the crippling challenge of starting over after losing everything. They also face an uncertain future with regard to their status.

Read moreThe EUMA After the Fall of Artsakh

With the collapse of Artsakh, will the EU further enable Baku’s irredentist agenda to seize Armenian territory as part of the opening of the “Zangezur Corridor” or will Brussels show the same initiative to sanction and deter Azerbaijan that it deployed in response to Russia’s aggression in Ukraine?

Read moreCan the International Community Reverse the Ethnic Cleansing of Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh? Part 1

The collapse of Artsakh is the failure of preventive diplomacy, the end of the human-rights-based liberal world governance system and can embolden other autocratic states to use force against small entities claiming self-determination to subjugate or eliminate them in other parts of the world.

Read morePhoto story

In Search of a New Home: Zorak

More than 500 forcibly displaced Armenians from Artsakh are now in the village of Zorak in Armenia’s Ararat region, where several families are living together in one house, some even in their trucks. Photojournalist Ani Gevorgyan tells their story.

Read more