The idea for this project came to my colleague Alexandra Livergant and I back in October. At the time, following the mass exodus from Nagorno-Karabakh, everyone was helping the refugees however they could. They were taking clothing, helping find apartments, and collecting money. This, however, was not going to be the solution, that was evident from the very first days. There would be help for a month, two, three… then what?

Only the government could offer a systemic solution to the problems of the Artsakh Armenians and the issue is not just money. Let’s assume everything somehow worked out, people found houses to live in and means to live by… I know from experience, months after immigration, even when the main issues have been figured out, the person is faced with the question: How do I keep on living? Why? Am I even needed?

I was endlessly meeting with the refugees from Artsakh and we were talking and talking… During one of these meetings Hasmik Arushanyan started telling me about the Karabakh dialect, traditions, about how they lived the last 30 years. At the end she suddenly said, “The memory, the conversations, the old photographs…are our home now.”

That is when I understood what needed to be done. They needed to be asked to speak. In those days, many good people found many ways to help the refugees from Karabakh. But the people from Artsakh themselves were not proactive in organizing much (their initiatives came later). Though their participation was crucial. I had already seen this very same situation play out. My compatriots were organizing aid for Ukrainians impacted by the war, and that was all well and right, but no one ever asked the Ukrainians for their input. But it is impossible to help the Ukrainians without the help of the Ukrainians. The same is true in the case of the Artsakh Armeians. There are things that no volunteer can do for them. They are central, not us.

During that conversation, we decided to start an oral history website, testimonials about life in Artsakh from different perspectives: language, cuisine, politics, history, people’s lifestyles…it would live online. But offline we would organize concerts, lectures, plays, culinary evenings.

I’m sure the initiative will come to be. It is already clear that many are interested and that is good. The more initiatives, the better.

This is a grand enough task, to encompass a whole life, but, “What can we do right now?” they asked. I saw the answer clearly, the image appeared before my eyes — a woman standing in front of a photograph of her house and telling us about the house. This is how it has to be. Because the key to the Karabakh tragedy today is not the word “war,” not “Genocide,” but “home,” specifically “home.” They lost their home.

With this in mind we spoke to Mark Grigorian, the director of the National Alexander Tamanyan Museum-Institute of Architecture and that is how the exhibition on Artsakh homes came about. Mark came up with the title right away, “My House in Artsakh.” The title hits the mark because the house is lost, but no one is prepared to renounce it. Physically the house is still where it has always been.

We put out an announcement, at first it seemed no one would be interested, that the initiative was doomed to fail. People would, rightfully, tell us that it is too soon, people are in shock, they are dealing with existential issues, they do not have time for this. And afterall the pain is so potent already, better not to poke the wound.

No, I insisted, this needs to be done now, later would be too late. People will disperse in different directions (it is already happening), memories will fade, the pain will diminish. The exhibition needs to show the pain, because it is impossible to speak about Artsakh without pain.

Then, it was as if something erupted. People started writing, sending photographs, telling their stories, thanking us. All of a sudden it emerged that this was important. Talking about it was painful, keeping silent was excruciating.

I watched their faces light up as they spoke about their houses. Unstoppably … joy, pride, longing, anger… no conversation was without tears. The story of the house began with a smile and ended with tears…

It was torturous. I apologized endlessly. Then again there would be the smile… memories of the tree in the yard, the neighbors, the cats and the dogs. The exit. The 30 hour journey without food and water. And now? Where are you now? Somewhere in the Massives, six of us, in one room, tears again. Impossible to speak of that life in the past tense.

House by house, a whole world took shape in front of eyes, one that no longer exists.

This sentiment was foreign to me. Very few in Russian would know this feeling. The infamous fathers and sons issue. Moving out of the family was considered an act of bravery in my youth. Here, six generations of the same family live under the same roof.

This does not keep them from having a contemporary life, a contemporary profession. Live in today’s world…but on their land.

In the midst of a storm, when everything around was collapsing, several centuries-old trees in Nagorno-Karabakh continue to stand firm as reminders that there are, after all, eternal values.

And with the September 19 tragedy, when the people of Karabakh left their ancestral home, they uprooted the centuries old trees and submitted them to oblivion.

Here are several monologues recorded for the exhibition. The exhibition opens on February 23, with many more stories about the homes in Artsakh.

Irina Pirumyan

Our house is in the center of the city [Stepanakert], not far from the square, at the intersection of Vazgen Sargsyan and Lusavorich [Gregory the Illuminator] streets. It’s made of stone, with nice little wooden balconies. Three floors, eight apartments. Built in 1953.The exterior walls are built in the same style that you see in Shushi, revealing the outlines of the stones. And the stones are enormous, very large. In the garden there are mulberry, walnut, cherry trees…

There is a fancy clothing store next door. Sergey’s “Optika” is opposite us. Everyone in Artsakh knew it. There is the chess club, old people who loved to play chess gathered there, played with dignity. The bank, school N8…

I have lived there since 1983, exactly 40 years. Everything in the house is connected with my husband. My husband, Oleg Pirumyan, was a famous musician, leader of a children’s vocal-instrumental ensemble. A one-man orchestra. He played bass guitar, rhythm guitar, synthesizer… He died in 1992, during the battles for the liberation of Shushi.

Educated people used to gather in our house. Artists, musicians, athletes. And we helped each other during the siege… Especially in the last four months, when there was absolutely no food. We stood in line for bread for 12-14 hours. At three in the morning, artist Martin knocked on my door with his wife. “Come on, hurry up! They are queuing up.” We ran to a stand. I’m the thousandth in line. At the other stand, I would be the three hundredth. We take water with us because we are all exhausted. Martin’s health is getting worse, so I help him. The main thing is to stay in the queue. It is suffocating, hard to breathe, you go out for fresh air and lose your place in the queue. I was getting half a loaf of corn flour bread the thickness of a cell phone, an orange colored, tiny piece. You eat it, then suffer through indigestion, and feel poorly.

We didn’t expect to leave the city. For the first five days after September 19, we helped those who came from the villages. People had been stuck in traffic, overnight in cars. There was no oil or butter, we cooked rice with water and took it to them. There was no electricity, we would start a bonfire in the yard to make tea.

Then we left. It was September 29. Before leaving, we threw all our valuables out of the second floor window. We were crying, we were panicking. We were throwing plates, glasses, and vases. Everything was breaking into pieces. We dragged the oven, which I had recently bought, and also threw it down. I was working three jobs to earn money for all of that.

I broke everything that could be broken. I took only the photos, a few favorite pictures without their frames, and the synthesizer – my instrument, the source of my revenue, without it I am nothing. I left the clothes and everything else.

My neighbor even set the bed on fire, something I did not have the courage to do. I left notes all over the house. I wrote in the kitchen: “May this not go down your throat.” I wrote “drown” in the bathroom. In the bedroom, “May those who sleep in my bed may not wake up!” There was a suitcase full of children’s clothes in the room, leftover from my grandchildren. I wrote, “May your children become refugees.”

I understand, it’s bad, it’s terrible, it’s wrong, but I was very hurt.

Nune Arakelyan

Everyone knew our house. It is the largest apartment building in the city. At the very end of Tumanyan Street. Once in its place was the Karabakh silk factory. A huge production plant that employed several thousand people. It was the largest enterprise in Nagorno-Karabakh. Many workshops, a culture house, kindergarten, dormitory. There was also the old bread factory. And of course, the Charles Aznavour Center, the jewel of our street.

During the first war, the factory was heavily bombarded. It was continuously hit with grad projectiles. And as a result, it burnt down. After the war, only the workshop was left, it was rumored that they had been sewing jackets for Versace. All the remaining structures were given to a private developer.

The construction of the apartment building was started by a diasporan entrepreneur. But then something happened… I think he couldn’t operate with our corrupt schemes. By the end of the construction, the building belonged to the state. Some of the apartments were bought by the elite, some were sold, others were given to the families of soldiers who had died in the war. I ended up there thanks to a preferential loan. I paid for 11 years and was almost done. There was only a little left, just over a million drams. A little more, and I could have taken a breath.

My mood would improve every time I set foot in the lobby. I was happy to be home. My son and I had been moving from one unfamiliar place to another for a long time. When my girlfriends found out that I got a house, they started bringing me different things. One bought a carpet, another a chandelier, and a third curtains.

It seemed to us that the building was not strong, that a slight wind could blow it over. But there was a two-story parking lot under the building. And it was during the second war, when we went down to take shelter did we see the huge pillars of concrete and cement that could withstand a ten magnitude earthquake. We felt fully protected, it was the most well-known bomb shelter in the area. People were brought there from the villages. They stayed for a day or two and left for Armenia. The place was big, it could fit more than a thousand people.

The building itself was not targeted but the [electricity] substation, which was right next to our house, was bombed, the bread factory was bombed. For a long while afterwards, they would find unexploded Smerch rocket munitions.

After the 2020 war, refugees moved into the first floors, mostly from Shushi. Families with many children were also accommodated there. The courtyard was loud and happy, even during the blockade. One or two months before we left Artsakh, a group of enthusiasts opened a children’s jamboree right in the yard. They made various things for the children, took care of them, and organized concerts.

I had a secret shelter for homeless cats in the parking lot. I went down several times a day to feed them. Most of the neighbors did not like animals, so I had to hide my venture. At night I would bring down hot water bottles for the kittens. They hugged the bottles to stay warm.

We were among the last to leave on September 29. The building was empty, only one family remained. There was a paralyzed woman there. I cooked a big pot of buckwheat for the cats. I also left them my entire supply of meat preserves in cans that I opened. The cats came out to see me off. “Hang on,” I told them. I thought it wouldn’t be long, we would return.

I put bags full of food by the door. If there are hungry people left in the city, it could be helpful. We all did that… jam, beans, a jar of honey that I bought for 15,000 drams, all our winter supplies.

I took photos, some clothes, some gifts…

And we left.

Galina Simonyan

That house was built by my great-great-grandfather, Alexander Shahverdyan. He was a wealthy man, a wine merchant. He had vineyards in the Martakert region. When I was a child, I remember, there were giant wine vats in the basement, half-meter clay jugs as tall as I was.

It was built in 1880. I know the date from the archive. Unfortunately, no other information was preserved. In the 1990s, the city archives burnt down.

The house is on the corner of Tumanyan and Lusavorich streets, two blocks away from the square. There were famous shops nearby: Mayak, Kultmag. The Drama Theater is a block from us.

Five generations of my family grew up in that house. My great-grandfather Samson Shahverdyan lived here. He had six children: Grisha, Misha, Siranush, Sonya, Nina, Rosa. He died in 1924. After his death, the state confiscated most of the house, leaving only three rooms to us.

It is a stone house, the walls are 80 centimeters thick. It is a traditional Armenian house with a long balcony, large yard, stables and outbuildings. When I was a child, I didn’t understand why my grandfather was so worried about the cleanliness of the yard, he would not allow anyone to litter. Every year, he would insist the city authorities repair the stairs, the roof, and paint the walls. He considered it his home. He was born and raised in that house, it was his native nest. And it didn’t matter that he wasn’t the owner anymore.

A stone staircase led to the first floor, next to it was a small table around which the kids would hang out until evening when it was time for the adults. Everyone used to gather there after work. Men played backgammon and dominoes, the women drank tea. Everyone would catch up and it was very pleasant.

There was a mulberry tree in the yard, it was as old as the house. The fruit was for everyone. The branches covered half the yard, and there was a bench in the shade of the tree. Together, we would shake the branches, stretch the cloth underneath so that no fruit fell to the ground. My grandfather personally distributed the mulberries, a bowl to each family, and after grandfather’s death, my father did the same.

I was seven when my younger aunt got married there. In the courtyard there were large pots where traditional khashlama and pilaf were being cooked. Musicians were playing, long wooden tables were lined up. The benches were covered with rugs, carpets, rags, whoever had what. There were 200 guests at the wedding. I remember the happy music, my aunt’s dress and the food.

In 2015, the building was deemed to be structurally unsafe. After the earthquake, the kitchen, which was an extension, collapsed. We moved to a new building. But the place was ours, and we used to go back there to visit the house.

I came to Yerevan on December 6, 2022 and could not return due to the blockade. Part of my family was in Artsakh. My two daughters and my brother with his family. They were among the last to leave on September 28. Azerbaijani patrols were already walking on our street. It was really scary. But they delayed until the last moment, they didn’t want to leave. The land holds you, the house holds you.

We left without our things. We took almost nothing. The only thing that I have of the old house is a small soup bowl, my grandmother’s, from the firebird porcelain set that had once been her dowry. That was all that was left.

We left the door open. We put the key under the rug.

Karina Petrosova

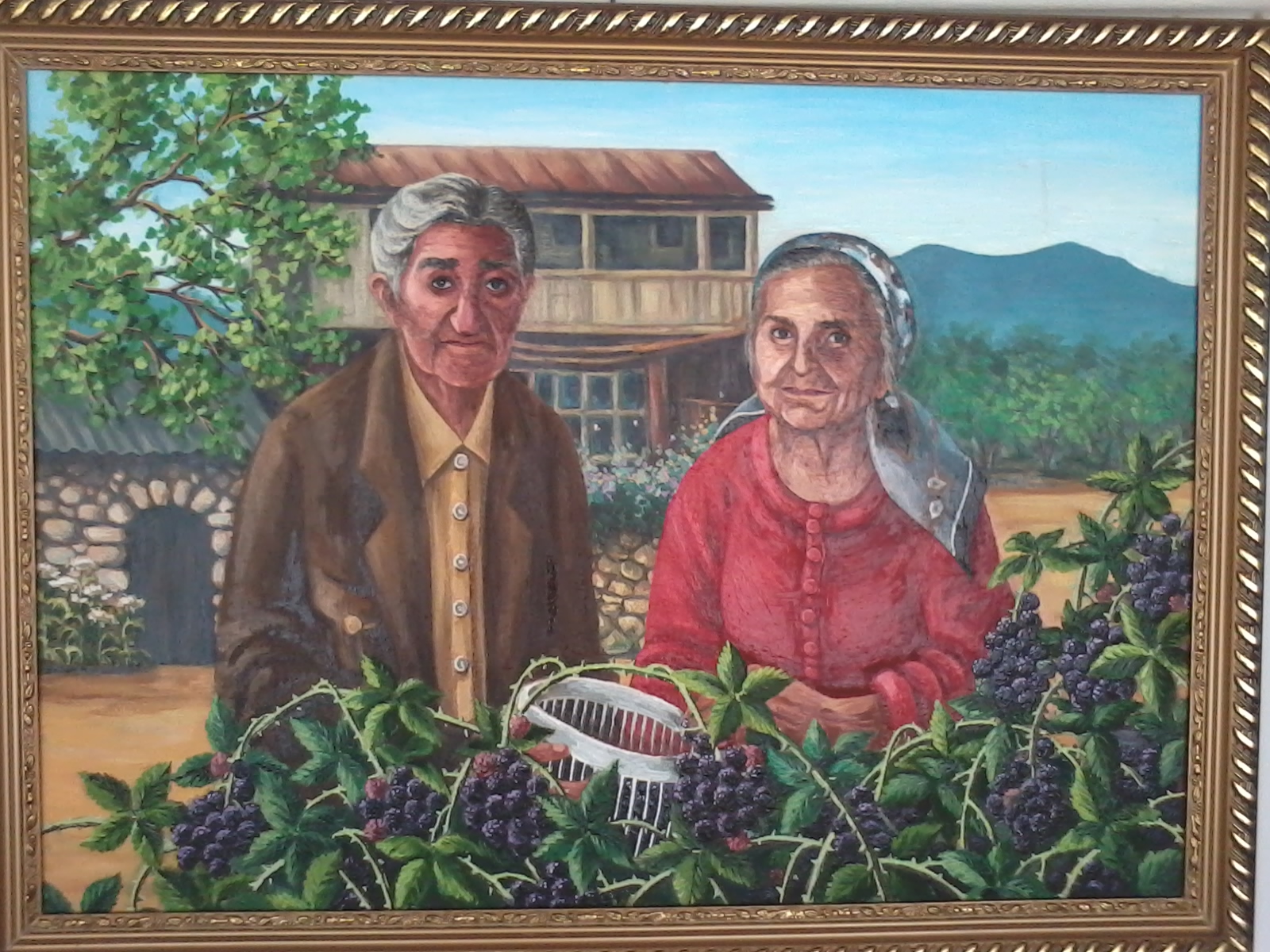

I brought this picture with me from Stepanakert. I took it out of the frame, wrapped it so that I could easily take it through the checkpoints. But it was left between the bags and was damaged. We reached the border in 39 hours. There were seven of us in the car, there was no air to breathe. We took almost nothing with us, only the children’s clothes and a picture. I saved it because our memories are tied to it.

The picture is of my grandmother and grandfather Vladimir Gevorgyan, in front of our house. In their youth, they lived in a small structure (it can be seen on the left in the picture) and built a house at the same time. They started building in the 1930s, laid the foundation, and then the war began. My grandfather was a major, and fought in the first Belorussian Front. He was wounded in the face, went through the whole war, after the war he served in Germany until 1949. He had many medals. I brought two. Orders of the second and third degree “for services to the Motherland.” Unfortunately, it was impossible to bring them all.

The construction of the house was completed only after my grandfather returned from Germany. It is in the center of Stepanakert, on Spandaryan Street. It is made of stone. They were building it for the longest time, almost 20 years. My grandparents did everything with their own hands. The result was very beautiful. Two stories, a big yard where we could play basketball and ride bikes. Four generations of our family had lived there. Even five. My nephews and nieces were born in that house in recent years.

On the ground floor there is a bedroom, a living room and a small kitchen. I remember my grandfather telling us fairy tales as we were being bombed. We lived on the second floor only in the summer. The roof used to leak during winter, it was cold. The entire roof was in ruins from shrapnel, there was no ceiling, and the windows were also broken. And we didn’t have money for repairs for a long time. But then gradually we put everything in order.

After the 2020 war, when my grandfather and grandmother had already passed, I repaired the house with my own hands. We always had friends around, socialized, and watched movies on the projector. There were many guests in the house at all times. We never locked the door and the gate. The key was alw6ays hanging on the lock. I left it there when we left.

The photos in the article were provided by the owners of the homes.

Spotlight Artsakh

Giving Birth in the Clutches of Blockade and Displacement

During the ten-month blockade of Artsakh, hundreds of pregnant women endured fear and deprivation instead of experiencing the joy of approaching motherhood. Photojournalist Ani Gevorgyan chronicles their challenges.

Read moreWe’re Home, And Yet We’re Not

In September, two families-in-law from Artsakh found refuge in the village of Yeghvard, Armenia, joining over 100,000 displaced Armenians facing similar challenges. Marut Vanyan, a journalist from Artsakh, provides insight into their experiences.

Read moreFrom Vayk’s Registration Center in Search of Aida

Irina Merdinyan traveled into the heart of a tragedy to help the forcibly displaced Armenians of Artsakh. In the midst of that experience, she was confronted with pain, confusion, anger and fleeting moments of joy.

Read moreThe Storks of Ranchpar

Several hundred forcibly displaced people from Artsakh have found refuge in the Armenian village of Ranchpar. As they struggle to make sense of their loss and create a new life, they hang on to the hope that, like the storks of the village who return each year, they too will one day return to their native Artsakh.

Read moreHealth, Women and War

With women and girls making up over half of the displaced people from Artsakh, what kinds of health and safety risks are they facing, and who is there to help?

Read moreSo That in the End, Good Triumphs Over Evil…

Specialists from the Ministry of Internal Affairs are working to alleviate the anxiety of the forcibly displaced children from Artsakh by offering psychological first aid. Their journey is captured in this photo story by Ani Gevorgyan.

Read moreThe Love on the Other Side of the Border: The Volunteers

As the ethnically cleansed Armenians of Artsakh streamed into Goris, they were met with hundreds of volunteers, among them diasporan Armenians, many of whom now feel a deeper connection and a stronger sense of purpose.

Read moreArmenians of Artsakh: Aching for Home

As the forcibly displaced Armenians of Artsakh struggle to comprehend the magnitude of their loss, memories of the homes and lives they were forced to leave behind suffocate them. Theirs is a story of being ripped from their roots, of pain and dispossession.

Read more