Armenia’s new Anti-Corruption Court is now operational and will hear criminal cases on corruption and civil cases of confiscation of illegally obtained assets. While this new court is now functioning, there are still vacancies for judges.

In April 2021, Armenia’s National Assembly adopted legislation on the creation of the Anti-Corruption Court, made possible through changes to the Constitutional Law “On the Judicial Code”. From July 30 – August 8, 2022, judges were appointed. After this they were given seals, and the work of the court began.

Not only have new cases already been sent to the Anti-Corruption Court, but also corruption cases in which criminal proceedings had begun but had not yet gone to trial. For example, the case against former Prosecutor General Aghvan Hovsepyan, accused of taking bribes and engaging in money-laundering, was sent to the Anti-Corruption Court.

According to Armenia’s Judicial Code the Anti-Corruption Court shall have at least 15 judges, of which at least 10 must be specialized in criminal corruption crime, and at least five – in civil anti-corruption.

Currently, however, the Court of First Instance of the Anti-Corruption Court has only 11 judges – three in the regions and eight in Yerevan. At the moment, there are four vacancies.

Appeals

There is currently no Anti-Corruption Court of Appeal, but there are Court of Appeal judges who hear cases relating to corruption and confiscation of illegally obtained assets, while hearing other cases.

According to Article 28.1 of the Judicial Code, judicial acts relating to corruption – both in the Criminal and Civil Courts of Appeal – are re-examined by at least six other judges. Thus it is stipulated that there be at least 12 judges hearing corruption cases.

Currently, however, there are only seven judges – three civil and four criminal – that hear cases in the Court of Appeal. There are vacancies for five judges.

On September 23, 2022, the Ministry of Justice presented a draft bill for public discussion for the creation of an Anti-Corruption Court of Appeal. This assumes changes in the Judicial Code and other laws.

According to the draft bill, the Anti-Corruption Court of Appeal will employ at least 12 judges, of which at least six will deal with cases on corruption crimes and at least six will examine appeals against judicial acts in civil anti-corruption cases. This means that appeals in the Anti-Corruption Court of Appeal will only be given to judges specialized in criminal anti-corruption, while appeals made in civil anti-corruption cases will only be given to those judges specialized in civil anti-corruption.

Court of Cassation

An anti-corruption chamber has been created in the Court of Cassation, which, according to Article 30 of the Judicial Code, will consist of 10 judges; two groups of five judges will examine the cases. One group will examine criminal cases and the other will examine civil cases.

Currently in the Court of Cassation, however, there are three judges in both groups, and there are four vacancies.

Criminal cases in the Court of Cassation which relate to corruption have been transferred to the group examining corruption cases.

Judge Sergey Chichoyan told EVN Report that they began working on July 1, 2022 and each judge has a 10 to 15 caseload. The group examining civil cases has only begun receiving new cases. Cases involving the confiscation of assets of illegal origin have yet to reach the Court of Cassation from the Court of First Instance.

To summarize, there are currently 24 judges examining corruption cases, and there are 13 vacancies.

The Judges

After the judges were appointed, their professional background and experience became a topic of discussion. Many felt that some of them did not have adequate experience to serve as judges. Below we present the appointed judges:

Judges of the First Instance Examining Cases of Confiscation of Illegally Obtained Assets

Karapet Badalyan was appointed as a judge of the Court of General Jurisdiction of Syunik region in 2020. Prior to that, he worked as an attorney and as a detective.

Ashkhen Gharslyan began working in the Court of Cassation in 2014. Before being appointed as a judge, she was the Acting Head of the Legal Examination Service of the Court of Cassation.

Narine Avagyan was Deputy Head of the Cadastre Committee of the Republic of Armenia from 2020 to 2022. Prior to that she worked at the Ministry of Justice, the National Assembly and the Civil Court of Appeal.

Judges of the First Instance Examining Corruption Crimes

Vahe Dolmazyan began his career as an investigator and then worked as a detective, senior detective, and prosecutor. In 2015, he started working as a senior prosecutor at the General Prosecutor’s Office investigating high-profile cases; and from 2020 to 2022 he was Deputy Prosecutor of Lori region.

Sargis Dadoyan worked as a senior detective in Armenia’s National Security Service from 2019 to 2022. Prior to that he was a detective.

Aram Grigoryan worked in Armenia’s Special Investigative Service as Advisor to the Head of the Service. Before that, he was a prosecutor and a detective. He also worked at the National Bureau of Examinations as an advisor to the director.

Suren Khachatryan worked from 2019-2022 in the Prosecutor General’s Office as Deputy Head of Department. Prior to that he was a detective.

Tigran Davtyan was a prosecutor from 2020-2022 and before that he worked as an assistant to a judge at the Court of First Instance.

Vardges Sargsyan was a senior prosecutor from 2020-2022, having worked in the Prosecutor’s office since 2015, prior to which he was a detective and an investigator.

Givi Hovhannisyan worked as an attorney from 2008-2022. Prior to that he was a detective for six years.

Mary Mosinyan was the head of the Legal Support and Service Department of the Staff of the National Assembly and prior to that, she worked as an assistant to a judge of the Criminal Court of Appeal.

Judges of the Civil Court of Appeal

Sergey Marabyan is a Candidate of Legal Sciences. In 2014, he was appointed as a judge of the Court of First Instance, specializing in criminal cases. He has been a judge of the Criminal Court of Appeal since 2018. Before being appointed judge, he worked in the Court of Cassation as an assistant – then advisor – to the chair. He has also worked as a prosecutor.

Mesrob Makyan was elected on October 17, 2022 as a judge hearing criminal corruption cases. Makyan has been a judge since 2004.

Karen Amiryan worked in the Prosecutor General’s Office before being appointed a judge. He has worked as a senior prosecutor and deputy head of department. Prior to that he worked in the Constitutional Court and was assistant to a judge of the Court of First Instance.

Armen Hovhannisyan worked as an assistant to a judge in the Armavir Court before becoming a judge of the Criminal Court of Appeal. He has also worked in the Court of Cassation and in government.

Judges of the Criminal Court of Appeal

Gor Torosyan was appointed judge in 2014 and prior to that was the director of a law firm.

Diana Hovhannisyan was appointed judge of the General Jurisdiction Court of Yerevan on October 10, 2018. Before that, she worked in different positions in the Civil Court of Appeal, including as assistant to a judge.

Armida Voskanyan was appointed judge of the General Jurisdiction Court of Gegharkunik region, and became the Chair of the same court three years later.

Court of Cassation

The judges of the civil chamber are Gevorg Gyozalyan, Liparit Melikjanyan and Artur Davtyan.

Liparit Melikjanyan is a Candidate of Legal Sciences. He has been an Associate Professor in the Law Faculty of Yerevan State University since 2014.

Artur Davtyan worked as an attorney and was also involved in politics. He was an MP for the ruling “My Step” faction but left the faction one day before being elected as judge of the Court of Cassation.

Gevorg Gyozalyan worked as an attorney prior to becoming a judge. He was a member of the board of the Chamber of Advocates, and lectured at the School of Advocates of Armenia. Gyozalyan represented Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan in the Robert Kocharyan vs Nikol Pashinyan case.

The judges of the Corruption Crimes Chamber are Sergey Chichoyan, Karen Bisharyan and Artak Krkyasharyan.

Karen Bisharyan was a judge in the Criminal Court of Appeal from 2021 to 2022 before being appointed to the Court of Cassation. He has been working as a prosecutor since 2013. From 2019 to 2021, he worked in the Department of Crimes Against Public Security of Armenia’s General Prosecutor’s Office as Head of Department.

Artak Krkyasharyan was the Deputy Chairman of the Investigative Committee prior to being appointed judge of the Court of Cassation. Before that he was Deputy Military Prosecutor. He began his career in 2000 as a detective.

Sergey Chichoyan has over two decades of experience as a judge. He was appointed judge in 1999 and is currently a member of the Supreme Judicial Council and was also a member of Chamber’s predecessor, the Legal Council.

Doctor of Legal Sciences, Professor Samvel Dilbandyan told us that judges of the Anti-Corruption Court should be professionals with experience as judges.

When the Anti-Corruption Court was first planned, a brief description in the legislative package stipulated that appointed judges have extensive experience including having been acting judges, former judges and legal scholars and must pass certain tests and interviews in accordance with the law.

However, of the 11 judges of the current Anti-Corruption Court of First Instance only Karapet Badalyan has experience as both a judge and lawyer, while Givi Hovhannisyan only has experience as a lawyer.

Problems Ahead

In the justification of the bill on the Anti-Corruption Court’s creation, it is stated that the specialized investigation of corruption cases will be ensured, thus increasing the effectiveness of trials in corruption cases.

However, the creation and functioning of this court has not been perceived positively. Moreover, even the need for a separate specialized court has come under question. According to Samvel Dilbandyan, pending corruption cases in the Anti-Corruption Court have already been properly investigated by judges before the creation of this court. “I don’t think that having a separate court will be effective,” he argues.

Lawyer and Candidate of Legal Sciences, Aram Orbelyan, says that the establishment of this court will create serious problems. According to Orbelyan, the fact that there is a law on “Confiscation of property of illegal origin” does not assume the existence of a separate court, because there are also codes on family, land, water, etc. If the same logic was applied, then a separate three-tiered court system should be created for all of them. The same is true for the criminal justice system. Why should corruption get special treatment while murder, robbery and other crimes do not?

He also points out another problem. For example, civil and anti-corruption courts will investigate cases based on the Civil and Civil Procedure Codes, and these two courts may, possibly, interpret the same legal norms differently and deliver precedential decisions that contradict the others.

According to Orbelyan, there are more important issues in the Armenian judicial system to tackle than creating a separate anti-corruption court, such as, for example, combating international crime, improving the efficiency of civil justice, and introducing e-justice systems. He recalls that in 2021 the courts put a hold on the electronic case assignment system for months because a criminal case of illegal influence on the electronic assignment of cases had been found and launched. As part of the investigation process, Armenia’s National Security Service seized access to the courts’ computer program server.

Costs and Benefit

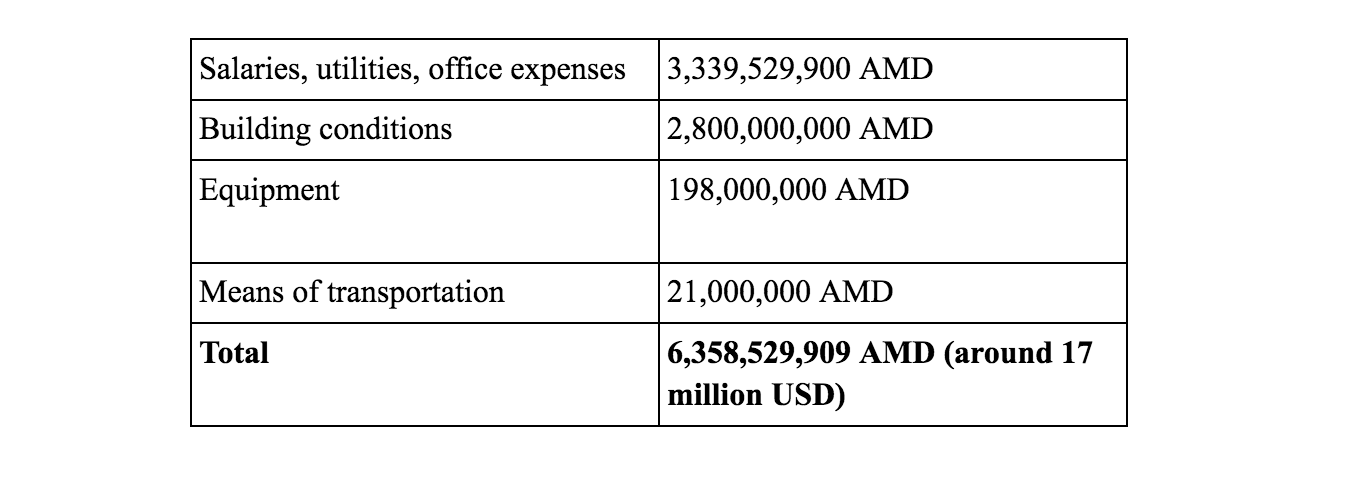

In July, 2020, in the justification for the bill creating the anti-corruption court, the Ministry of Justice had anticipated the following preliminary costs for 2021 to 2023:

These documents do not include what quantifiable benefit there is to having a separate court. For example, what type and how many corruption cases will be examined and what revenue will this secure for the state budget? Also, what impact will it have on the fight against corruption?

Political Subtext

In the public discourse on anti-corruption courts, the sense that their aim is to persecute and confiscate the property of former officials is palpable.

Orbelyan also considers the establishment of these courts problematic given statements made by the authorities: “In one interview, the authorities say they asked one of the detectives, ‘Why don’t you take the cases to court?’ and they said ‘Take it to court, so the court will ruin the case?’ It was after that, that the Anti-Corruption Court was created. Subsequently the former Chair of the Supreme Judicial Council Gagik Jhangiryan said in an interview, ‘When I was military prosecutor, I used to choose the judges so that they would at least make normal decisions in those criminal cases; that is, the prosecutor chose the judges…’”

Samvel Dilbandyan does not see a political motive. According to Dilbandyan, Armenia has ratified the UN Convention against Corruption and undertaken commitments to effectively fight corruption.

“The state is obligated to combat corruption –– a priority in every democratic state. Those courts have been created to implement justice not for previously committed crimes but for corruption cases in general,” says Dilbandyan.

Law & Society

“Smart” Barns Require “Smart” Calculations

Armenia’s government launched a state assistance program in 2019 for the creation of what they called “smart” barns to improve livestock care and increase milk production. Araks Mamulyan looks at the challenges and shortcomings.

Read moreSpecialized Personal Assistants for People With Disabilities

Armenia’s government is implementing a legal framework for specialized personal assistants for people with disabilities to ensure their right to live independently and be integrated into their communities. While the initiative is long-awaited, it remains to be seen how it will be realized.

Read morePutting the Brakes on Bookmakers in Armenia

Although betting companies are among the largest taxpayers in Armenia, the state has decided to implement laws restricting ads for online betting and lotteries to mitigate the spread of gambling in the country.

Read moreEnlargement of Communities: Problems and Challenges

The large-scale community enlargement program that launched a decade ago in Armenia is ending this year. Hasmik Baleyan looks at the shortcomings and effectiveness of the program.

Read moreMedical Sterilization: Voluntary, But Not for Everyone

Draft legislation addressing voluntary medical sterilization was unveiled for public discussion in July 2022. Some of its provisions were deemed highly problematic, particularly by human rights defenders. Astghik Karapetyan explains.

Read moreDeclaring Income and Assets: Risks and Opportunities

Starting from 2024, the declaration of income and assets will become mandatory for all citizens of Armenia. Araks Mamulyan looks at the advantages and problems of the program.

Read moreGrave Insult: Criminalization and Decriminalization

The amendment that criminalized “grave insult” in Armenia was in effect for only ten months. On July 1, 2022, Armenia’s new Criminal Code decriminalized grave insult after public pressure. Araks Mamulyan explains.

Read moreWhy Are Reforms in Armenia’s Mental Health Sector Being Delayed?

While planned reforms in Armenia’s mental health sector are constantly being delayed, the rights of people continue to be violated. Sona Martirosyan explains.

Read moreDangerous Work: Accidents in the Workplace

Health and security protocols are not always upheld in workplaces in Armenia, often leading to employees getting injured.

Read more