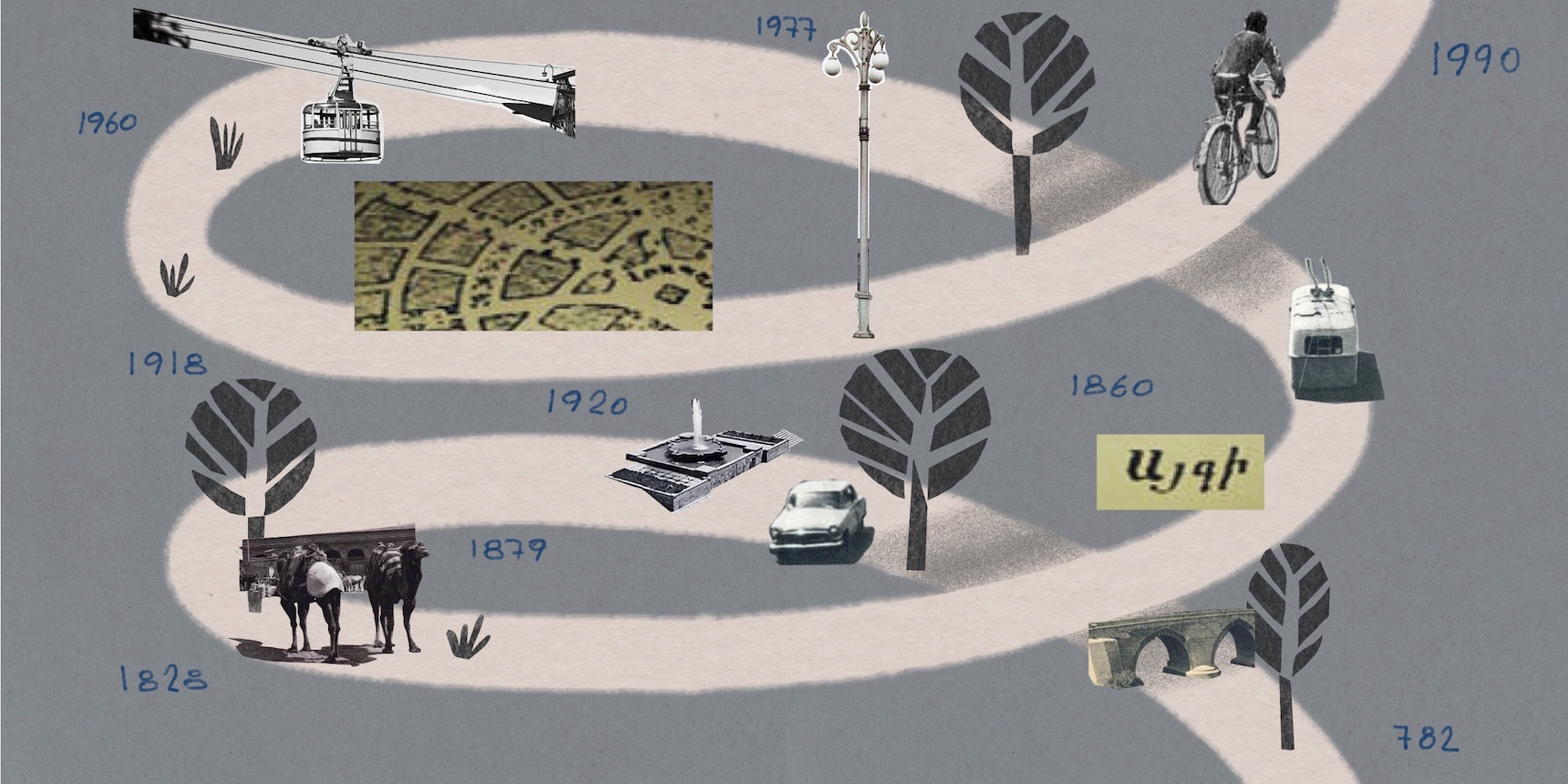

Yerevan, Armenia’s 12th capital city, officially considered to have been established in 728 BCE, [1] has had a significant place in Armenian history. And while its transformation through the millennia is not often apparent amid the dust of construction, high-rises in place of dilapidated buildings and deforested areas and parks, historians attest that Yerevan was once renowned for its gardens,[2] preservation efforts and municipal governance system.

In the 12th and 13th centuries, Yerevan had a population of 15-20,000. During this period, the position of mayor was granted to the wealthy landowners. When Armenia came under Mongol rule, Avetents Sahmadin [3], the richest man in the city, in 1264 bought all of Yerevan as his own estate. According to historians, at the end of the 13th century and beginning of the 14th, an individual named Husik is mentioned as the owner of Yerevan. [4]

Yerevan always suffered the brunt of foreign invasions against Armenia. This included Tamerlane’s invasions in 1386, when the city was destroyed and 500 residents were killed. [5] After the death of Tamerlane (1405), the Karakoyunlu and Akkoyunlu tribes established their rule in Asia Minor Yerevan became the administrative center of northeastern Armenia.

In the 16th century, a struggle to dominate Armenia began between Iran and Turkey. Historical accounts provide extensive insights into Armenia’s subjugation by both Persian and Turkish rule, how Yerevan was destroyed, how tens of thousands of people were captured from the city and surrounding settlements.[6]

Following the Ottoman-Safavid War (1532-1555), a Turkish-Persian peace treaty — the Peace of Amasya — was signed in 1555, and Armenia was divided between Ottoman Turkey and Safavid Persia. Yerevan remained a part of Persia, however, Turkey continued its attempts to recapture it.

After the 1826-1828 Russo-Persian war, the Erivan (Yerevan) Khanate was passed from Persian to Russian rule. With the Treaty of Turkmenchay, the “Armenian Marz” was formed under Russia. It lasted from 1828-1840. In 1849, the Yerevan region [province] was created and on January 1, 1850, the city of Yerevan became its administrative center.

As a part of the Russian empire, within 50 years (1829-1879) the population of Yerevan increased from 11,463 to 12,449 (986 people). The reason for the low rates of demographic increase wasn’t only the harsh political and living conditions, but also natural disasters: Getar flooded the city twice in 1860 and 1873, there were eight strong earthquakes, epidemics of cholera and plague. [8] However, it was during this period, in 1856, that the first blueprint of Yerevan was approved, and by 1863, one of the main streets named after Governor Astafev (now Abovyan Street) was constructed. Since then, the streets began to be officially named. Until the end of the 19th century, a number of streets had already been named: Nazaryan Street (now Amiryan), Behbutyan (now Pavstos Buzand), Tsarakan (now Arami), Tarkhanyan (now Pushkin), Nahangayin (now Republic), Ter-Ghukasyan (now Nalbandian), Armyanskaya (now Mashtots Avenue).

This time period was central for the establishment of a city governance system when the city duma, the administration and self-governing bodies were created. On June 16, 1870, Alexander II approved the Statute of Municipal Reforms, which granted internal autonomy to cities. Preparations for city election assemblies, city duma and administration elections began. Election assemblies were to meet every four years to elect the city duma. Citizens subject to Russian rule, who were above 25, had property and paid taxes to the city had the right to participate in the elections. City duma was a legislative body that had 72 members.

The city duma, in its turn, elected the city administration by secret ballot. The latter was an executive body consisting of a president, two members and a secretary. The chairman of the administration was the mayor. His election was approved by the governor of Yerevan.

The first municipal elections took place in the fall of 1879. On October 1, the first Duma was opened with 66 members. Diocesan school teacher Hovhannes Ghorghanyan was elected mayor.

This governance system continued to operate until 1918 with minor changes. During this period Yerevan had 10 mayors.

- Hovhannes Gorghanyan: 1879-1884

- Barsegh Geghamyan: 1884-1893

- Levon Tigranyants: 1894-1895

- Aram Buniatyan: 1895-1896

- Vahan Ter-Sargsyan: 1896-1898

- Isahak Melik-Aghamalyan: 1898-1904

- Hovhannes Melik-Aghamalyan: 1904-1910 and 1912-1914

- Hovsep Tigranov: 1911-1912

- Sumbat Khachaturyants: 1915-1917

- Tadevos Toshyan: 1917-1918

What problems did the city council solve? The history and lifestyle of Yerevan are best presented in the press of the time, and the “forefathers” of the city’s periodical press were “Psak”[8] and “Arogjapahakan” [Health] Newspaper.[9]

“A question was raised regarding the cleanup of garbage in the streets. The question was health-related. In that session, it was decided that the city administration form a list of how much money approximately would be required to take that garbage out of the city streets…The second question concerned whether it was necessary to take rent from caravans passing through or lodging on urban lands or not. A decision was made to demand a penny for each camel, horse, or ox, no matter how long they were kept in the city. The solution of this issue was a way to enrich the city treasury.”

Issue N.3 “Psak” newspaper, 1880.

The mayor of Yerevan and the city administration had to exert serious efforts to get the residents to participate in the city’s governance.

“Before, when the right to govern the city was in the hands of the Police, citizens always complained that the Police did not care about the city…Starting from October of last year, the right to govern the city was given to the people. From that moment, residents of Yerevan, you are the owners and the governors of your city. Your activities will show whether you are capable of autonomy or not. Until this point, the residents of Yerevan were used to doing everything because of an order. If they were ordered to clean their garden, toilet, street or bazaar, they cleaned it reluctantly, and if the Police did not make a sound, everything remained dirty.”

Issue N. 22, “Psak” newspaper, 1880.

The unsanitary conditions of the city caused epidemics. However, there were other reasons for the epidemics that were recorded in the press of the time.

Becoming a part of Russia also led to the introduction of alien customs to Armenians. One of those new customs was proshti — kissing each other on the lips when greeting. And so Armenian merchants returning from different countries along with their products brought with them “a hideous product” — syphilis — with which they infected not only their wives but also all those with whom they kissed so diligently.

“Among us, Armenians in Russia, a very bad, new habit is spreading day by day, which is also spreading among our rural population. It is the custom of proshti. This custom is mainly practiced by the Russian rural and middle class where people would kiss each other on the lips for no reason on the major holidays – Easter, New Year – and not once, but twice…”

Issue N.1, “Health” newspaper, 1881

Just like today, at the end of the 19th century, the problem of street lighting and water trucks (used to clean the streets) were important in Yerevan.

“We heard that Mayor Geghaments is bringing new lanterns and new water trucks for watering the streets. The city streets are being tidied up with great effort.”

“Yerevan Announcements”, March 17, 1885.

According to the 1897 census, there were 830,000 residents in the region of Yerevan. The population of Yerevan itself was 29,006. According to the same census, in 1897, Tbilisi had 160,000 inhabitants, Baku 112,000.

Due to epidemics, poor water quality, and a flawed healthcare system, the rate of infant mortality was high in Yerevan. In 1886 it was 64.3% and in 1896 it had climbed to 84.7%. [10]

Yerevan entered the 20th century with the necessary infrastructure. In December 1902, the Alexandrapol-Yerevan railway began to operate and four years later, the Yerevan-Julfa railway did as well. In the same year, “the city transport” was put into operation: horse-drawn carriages and horse-drawn trams for the construction of which specialists from Europe were invited. According to the contract, the horse-drawn transport would operate for 36-46 years.[11] Yerevan mayor and the deputies of the duma were sure that in the coming 50 years, it was unlikely that a vehicle would be invented to replace the horse.

In 1907, a hydroelectric power plant was constructed on the Hrazdan River by the Amper Company. Another power plant by the Shustov and Sons Company was built to meet the needs of the brandy factory exclusively.[12]

In 1912, Yerevan had 36,836 inhabitants.[13]

During the First World War, tens of thousands of Western Armenians who survived the genocide took refuge in Yerevan, many of whom became victims of famine and epidemics. In 1917, 17,595 emigrants were registered in Yerevan.[14]

Despite being exhausted by emigrants, famine, and epidemics, Yerevan nevertheless found the strength to defeat the Turkish army marching toward it in May 1918.

On May 28, 1918, Armenia regained its independence. Yerevan, which had a history of being an administrative and political center for more than 400 years, became the capital of the newly independent republic. In July 1918, the first government of the Republic and the Armenian National Council moved from Tbilisi to Yerevan, consulates were opened.

After the establishment of the First Republic of Armenia, Yerevan was governed by the National Council headed by Aram Manukyan for about two months.

The law on self-government (zemstvos) was developed and implemented. Local self-government was introduced in a number of provinces (Yerevan, Ejmiatsin, Ijevan). Urban autonomies were reorganized. There were conciliation and arbitration courts in Yerevan (also in the provinces). The capital housed the district court, the courthouse, and the senate. In 1920, trial by a jury was instituted. The proceedings and the administration of institutions were conducted in Armenian.[15]

The problems of the city, regardless of the alarming political situation, were in the pages of the press.

“Our city sparkles with its garbage heap exhibition. The wind scatters the piles of garbage, certainly out of proportion, over the city… Dead bodies of horses, dogs and other animals remain lying on the streets for days in various parts of the city. A dead horse has been lying on Astafyan Street for days.”

Issue N.3, “Zhoghovurd” newspaper, August 22, 1918.

During the years of the First Republic, Yerevan had two mayors:

- Tadevos Toshyan, 1917-1918,

- Mkrtich Musinyants, 1919-1920.

The history of the preservation of Armenian brandy is also connected with Musinyants. During the First World War, when he was the head of the Shustov Brandy Factory, the Russian Empire imposed a law on prohibition. Musinyants personally saved a unique collection of alcohol and spirits from destruction, providing the opportunity to resume production later, as well as bringing a large amount of foreign currency to the First Republic.

In those difficult conditions, the National Library was founded in Yerevan in 1919. In the same year, a decision was made to open a university.

“In these turbulent days of threats to the homeland, the foundation of the highest educational institution is laid in the capital of Armenia. With the realization of the freedom and ideals of the martyred, it seems that the Armenian language will be restored and it will dominate the newly opened higher educational institution, not for formality, but for practicality and fundamentality.”

Issue N.2, “Yerkir” newspaper, 1919.

On the opening day, the university had eight lecturers and 200 students. The plan was to open a conservatory, medical and agricultural institutes in Yerevan by the fall of 1920.

The Ethnographic-Anthropological Museum was founded. The first exhibition of the Union of Armenian Artists was organized with the paintings of Gevorg Bashinjaghyan, Yeghishe Tadevosyan, Martiros Saryan, and others. In 1919, the theater school, music, Armenian language, pedagogical courses, and other educational institutions were operating in Yerevan.[16]

Alongside the Ministry of Public Education and Arts, the Antiquities Protection Committee of Armenia was created, the purpose of which was the protection of monuments and their research. Alexander Tamanyan began to develop the plan for Yerevan in accordance with the requirements of the European construction of cities.

However, the capital was still far from internal peace and calm. “Is Yerevan a city or a battlefield? Any person who enters Yerevan for the first time and wants to spend the night asks themselves this question. For fun, for a moment of pleasure or for the sake of being called ‘citizens’, a number of individuals have the habit of shooting their guns,”[17] the newspapers wrote. What should citizens do? Contact the city police. However, both today and during the First Republic, citizens were dissatisfied with the police and, in particular, with the chief of police. “Why isn’t there a police force? There isn’t a police chief who is fully aware of his duties.”[18]

Armenia’s First Republic fell in 1920. The 11th Army invaded Yerevan. Armenia became part of the Soviet Union. In Yerevan, the members of the executive committee of the city council replaced one another. From 1921-1923, eight political council presidents changed in Yerevan.

After Armenia became part of the Soviet Union, Yerevan was governed by the City Council of People’s Deputies, which was formed by an equal and fair election for a two-year term.

Tamanyan, who continued to work on Yerevan’s city plan, wrote in 1923: “The prevailing color of the city was dreary. It was as if they were built for eternal mourning. Row after row, there were dirty houses.”[19]

“When this new city was born, I was present,” wrote Martiros Saryan, “It was born on paper, and what is created on paper, I believe in it because I am an artist. I was sitting next to Tamanyan. He was sketching and said, ‘Martiros, here there will be a university district, here there will be a square…’ Who knows what kind of confusion of styles would have been created if Tamanyan had not revived and repaired our tribal architecture.”[20]

The Soviet period, however, had its authorities, the “labor organizations.” In 1924, Tamanyan had sketched a semicircular square near the St. Poghos-Petros Church. However, the city government decided to demolish the church and build a cinema named “Moscow” in its place. Tamanyan’s arguments that St. Poghos-Petros was a unique structure of the 5th-6th century with its 6-7 layers of murals were left in vain. The response of the city government was, “There is a decision made by many labor organizations to abolish the St. Paul-Petros Church, which has been approved by the political council presidency.”[21]

The church was destroyed.

In the 1920s and 1930s, other buildings of historical and cultural significance were demolished in Yerevan: the Yerevan Fortress built in 1583, the Gethsemane Chapel built in the 1690s, the Holy Mother of God Catholic Church built in 1693-1695, the 19th-century Mler cemetery and chapel, the Abbas Mirza Mosque, St. Grigor Lusavorich Church built in 1900, St. Nicholas Cathedral built in 1904.

In the 1930s, structures with religious and cultural value were not the only thing being demolished. Human relationships were falling apart. The archival documents of the 30s and 40s, the press of those years, personal letters and memoirs of writers depict a painful picture. In the literary world, almost all writers were accusing each other of anti-Soviet and nationalist schemes.The lives of three of the 32 figures who led Yerevan during the Soviet years were cut short by shooting, four were repressed or exiled. Years later, they were exonerated.

In Yerevan, the “old” was being demolished and the new was being built: the Rubber Factory, the Kanaker Hydroelectric Power Plant,(Քանաքեռ հէկ), the tram was put into operation. In 1933, Alexander Spendiaryan’s opera “Almast” was staged in the newly built Opera and Ballet Theater.

“The proletariat and laborers of Soviet Armenia are celebrating another victory in the cultural revolution. The first opera theater was opened in the capital of Soviet Armenia. Long live our new culture, national in form and socialist in content.”[22]

Issue N.2, “Grakan” newspaper, 1933.

However, the Second World War began and in 1941, thousands of Yerevantsis went to the frontlines. After the war, German prisoners of war who remained in Yerevan built the Victory Bridge on the Hrazdan River. The buildings of the Ararat Brandy Factory were also built by German prisoners of war.

After the war, the 90,000 Armenians who repatriated to Soviet Armenia in 1946-1948 brought new color to the cultural and civilized life of Yerevan.

The first big celebration of the founding of Yerevan was in 1968 when the city’s 2750th anniversary was commemorated. Judging by the press publications of that year, it was a chance to show Yerevan’s ambition to be among the world capitals.

“There are very few 2750-year-old cities in the world. Yerevan, which is older than the world-famous Rome, has gained world recognition in the last five decades. If before it was a pre-revolutionary city with a population of a little over four tens of thousands, as much as the city’s current student population, the capital of Soviet Armenia now has 708,000 residents. This is a rare increase by world standards.”

“Grakan” newspaper, September 13, 1968.

Respectable age, however, is not the only virtue of Yerevan.

An industry equipped with modern technology was created in Soviet Armenia. In Yerevan, factories of transformers, portable power plants, generators, precision measuring instruments, hydro pumps, electric lamps, machine tools and chemicals began to work.

“The population of Yerevan, according to our calculations, will reach one million by the end of 1977,” the press reported. [22]

Garbage collection, traffic jams, polluted air… These are only some of the problems of today’s modern capital. What problems did the people of Yerevan have 50-60 years ago?

“There were no fresh carnations in flower shops at the corner of Lenin Avenue and Sverdlov Street, Pushkin, Sayat-Nova Streets, Moskovyan and Barekamutyun Streets. The business of distributing and selling flowers in our beloved 2750-year-old Yerevan faces trouble. Soon, thousands of guests will come, what should we give our relatives?” “Avangard”, October 10, 1968.

References:

[1] Margarit Israelyan, Two New Urartian Inscriptions, Bulletin, USSR State Government, 1951, N 8.

[2] Tadevos Hakobyan, History of Yerevan (From Ancient Times to 1500), Yerevan, 1969, p. 200.

[3] Ibid., p. 217.

[4] Ibid., pp. 217-218.

[5] Yervand Shahaziz, Old Yerevan, Yerevan, 1931, page 30.

[6] Zakaria Dekavag, History, Vagharshapat, 1870, page 13.

[7] Tadevos Hakobyan, History of Yerevan 1801-1879, Yerevan, 1959, p. 573.

[8] Published in 1880-1884, ed. Vasak Papajanyan.

[9] Published in 1881-1884, ed. Levon Tigranyan.

[10] Tadevos Hakobyan, History of Yerevan (1879-1917), 1963, p. 185.

[11] Ibid., p. 316.

[12] Ibid., page 46.

[13] Documents on the history of the Yerevan province, art. 94:

[14] Development of Yerevan after the annexation of Eastern Armenia to Russia, collection of documents, 1801-1917, comp. T. Hakobyan, Yerevan, 1978, art. 415:

[15] Ararat Hakobyan, Republic of Armenia, 1918-1920, Yerevan, 1992, p. 9.

[16] Simon Vratsyan, Republic of Armenia, Paris, 1928, p. 324.

[17] “Ashkhatank”, 1919, N 40, Yerevan.

[18] Ibid.

[19] A. Khachikyan, Yerevan jubilee. Jubilee chronicle of the 2750th anniversary of the city, Yerevan, 1972, page 11.

[20] “Yerekoyan Yerevan”, 1968, N 246 (3315).\

[21] Lola Dolukhanyan, “Culture”, 1990, p. 22.

[22] “Avangard”, October 15, 1968.

Magazine Issue N32

The City

Yerevan, the capital of Armenia, where one third of the population lives today, has borne witness to sweeping social, political and economic changes for centuries. It is considered the pulse of the nation, where critical decisions on the future of the country are formulated, where promises are made and sometimes broken, a city that has hosted immigrants, emigres and tourists, an urban center where gentrification and rapidfire development threaten its relationship with its residents, when a municipal election becomes more about national issues, instead of urban needs and requirements. This month’s magazine issue entitled “The City” features articles that delve into the nuances of municipal elections, present the political forces running for city council and the history and lost stories of an ancient capital.

In Yerevan’s Mayoral Election, Coming In First Won’t Be Enough

While city councils are typically primarily concerned with issues like building permits, public transportation and garbage collection, several opposition candidates in the upcoming municipal election in Yerevan are channeling the post-war zeitgeist in which national security is the top issue.

Read moreOf Ownership and Citizenry

Ahead of municipal elections in Yerevan, Roubina Margossian writes that this fascinatingly adaptable city has hosted thousands of immigrants and a record breaking number of tourists this year, but its resources are running thin and the time before it can no longer catch up with its own development is fast running out.

Read moreMagazine Issue N31

Sport

Sports have always played a crucial role in societies, contributing to the physical, mental, and social well-being of individuals, communities and nations. Their significance extends beyond mere entertainment, fostering unity, discipline, resilience and personal growth.

While headlines in Armenia, Artsakh and the region are dominated by conflicts and despair, sports and sporting events provide respite and give people, young and old, an opportunity to improve their health, and a platform for people to come together and support their athletes and national teams. Sports also can lift people up in times of crises and become a source of healing. They provide young people with role models, encouraging them to lead more active and healthier lives.

In this month’s magazine issue entitled “Sports” we present articles covering the spectrum of different sports – from special schools preparing future athletes, to water polo and gymnastics, to the more traditional Armenian sports, such as football, weightlifting and wrestling.

Armenian Wrestlers Locking Victories

Wrestling is a mainstay sport in Armenia. Reminiscent of the traditional “kokh” sport popular among Armenians in the past, which was often accompanied by folk tunes during competitions, wrestling remains a favorite among sports fans.

Read moreApproaching the Barbell

While Armenia may be small in size and power, its national weightlifting team is one of the best in Europe. Armenian weightlifters have electrified the public with their numerous victories, and they continue to inspire each other with their record-breaking achievements.

Read moreArmenian Football Looks Ahead

While it is generally accepted that Armenians fare better in individual rather than group sports, football, the world’s number one group sport, still remains a favorite, and despite promising developments in the sport, challenges persist.

Read moreWater Polo, War and the Bond Between a Father and Son

Henrik Hakobyan, captain of Armenia’s national water polo team, was killed by an Azerbaijani missile on the first night of the 2020 Artsakh War. Three years on, his legacy continues to inspire water polo athletes.

Read moreTo Paris and Beyond: The Legacy of Gymnastics in Armenia

Despite many challenges and hurdles, the legacy of the forefathers of Armenian artistic gymnastics — Albert Azaryan and Hrant Shahinyan — continues on today as Armenian gymnasts prepare to bring home more medals.

Read moreA Hub for Future Athletes

A sports college, located in a suburb of Yerevan, is one of Armenia’s most important athletic institutions that strives to prepare athletes for the country’s national teams, to even become Olympians.

Read more