Q1: What are the origins of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict?

Throughout its history, Artsakh has been a predominantly Armenian-populated region. Throughout the Middle Ages, it maintained autonomy under local Armenian nobility while under the Persian Empire. In the early 1800s, the Russian Empire conquered the territory (at the time known as the Karabakh Khanate) and implemented several administrative-territorial reforms. In the 1860, Artsakh fell under the Yelizavetpol Governorate, which also included Armenia’s Syunik region. The Governorate as a whole had a mixed ethnic composition with Armenians and Tatars being the two largest groups.

When the first clashes occurred between Armenians and Tatars in 1905-1906, the Russian administration utilized them to deviate the attention of the population away from anti-imperialist sentiments.

In autumn 1917, after the rise of the Bolsheviks to power and the outbreak of civil war in Russia, Transcaucasia became politically cut off from the rest of the territories of the Russian state. Under these conditions, the Transcaucasian Commissariat took control of Transcaucasia. It convened the Transcaucasian Sejm (parliament) in February 1918, set out to determine the government’s organization and form the authorities of the region. The Sejm was short-lived, and between May 26-28, 1918, Georgia, Azerbaijan and Armenia declared their independence.

After the 1918 independence of Georgia, Azerbaijan and Armenia, there were two main principles to solve border issues: by adopting the borders of former Russian administrative divisions and by drawing new borders considering local demographics. Only the Armenian side was in favor of demarcation by the ethnic principle, which later caused conflicts in Armenian-populated Lori, Javakhk, Nakhichevan, Zangezur and Karabakh.

Q2: What was the status of Nagorno-Karabakh from 1918 to 1920?

In 1918, the Armenians of Karabakh established the Council of Commissioners, the first democratic government over the territory. In 1918-1920, Karabakh had all the elements of statehood, including an army and legitimate authorities. In 1918, the Turkish command issued an ultimatum to Karabakh՛s government to accept Azerbaijani sovereignty. The Armenians of Karabakh maintained their resistance until the Ottoman Empire surrendered to the Allied Powers and withdrew from the First World War in October 1918. Later, a British command came to occupy the area. After repeated attempts, they eventually convinced the Armenians of Karabakh to accept Khosrov bey Sultanov as a temporary governor until final boundaries could be finalized by the Paris Peace Conference. The decision was overturned within days, however, as massacres of Armenians immediately followed Sultanov’s arrival.

During the two years of the Karabakh government’s existence, it organized ten congresses which tried to solve various issues concerning the daily life and self-defense of Artsakh’s people. All the congresses held in 1918-1920 rejected the demand of including Artsakh in Azerbaijan except for the seventh congress, which decided to temporarily place Artsakh within the borders of Azerbaijan until the Paris Peace Conference. The decision, however, was later invalidated because of the attempt of Sultanov’s military invasion. Importantly, well-documented facts indisputably confirm that the population of Karabakh did not recognize the authority of the Azerbaijani state in the period of 1918-1920.

However, after establishing Soviet rule over Azerbaijan’s territory on April 28, 1920, the Red Army occupied Karabakh and declared it a disputed territory. On November 30, 1920, the government of Soviet Azerbaijan issued a statement, and the Chairman of the Azerbaijani Revolutionary Committee (Azrevkom) Nariman Narimanov, and the Azerbaijani People’s Commissar of Foreign Affairs Mirza Huseynov stated that territorial disputes with Armenia were abrogated. As a result, Nagorno Karabakh, Zangezur and Nakhichevan were recognized as integral parts of Soviet Armenia.

Q3: How did Nagorno-Karabakh fall under Soviet Azerbaijani rule?

On June 3, 1921, the Caucasus Bureau of the Russian Communist Party unanimously adopted a decision “to mention in the Armenian Government’s declaration that Nagorno-Karabakh belongs to Armenia.” On June 12 of the same year, a decree affirming the final legal status of the territories as part of Soviet Armenia was issued by the government of the Armenian SSR. The news was also published in Baku, and the people and authorities of Azerbaijan confirmed the unification of Karabakh with Armenia. A month later, on July 4, the plenary session of the Caucasus Bureau (Kavburo) decided “to include Nagorno-Karabakh in Soviet Armenia.”

However, the next day, because of Stalin’s intervention, Karabakh – within its historical and geographic borders – was handed over to Soviet Azerbaijan, providing a “broad regional autonomy” with Shushi as its administrative center. To ease the tension within the Armenian community, the mountainous portion of the territory was later granted the status of the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO).

Q4: How did the seven districts across Nagorno-Karabakh emerge?

The process of the insertion of Nagorno-Karabakh into Azerbaijan was completed in 1924. During that period, Azerbaijan initiated Karabakh’s partition policy. Azerbaijani authorities tried to create a buffer zone between Armenia and Mountainous Karabakh; therefore, they established an autonomous administrative unit, known as “Red Kurdistan.” Later on, the decision to have a separate Kurdish autonomous region was reversed. “Red Kurdistan” was reorganized from one autonomous unit into several districts that fell directly under the jurisdiction of the Azerbaijani SSR – not part of the NKAO.

Later on, the districts of Kelbajar (Karvachar), Lachin (Berdzor), Kubatli (Sanasar) and Zangelan (Kovsakan) were established between Armenia and Karabakh. Furthermore, Jabrayil (Jrakan), Fizuli (Varanda) and Agdam (Akna) districts were also created. The Shahumyan district was another directly Baku-controlled district; it was directly north of the NKAO and had a predominantly Armenian population but was not included in the NKAO. Nevertheless, its population also expressed the will to unite with Armenia in tandem with Karabakh in 1991.

Q5: How did Soviet Azerbaijan treat Nagorno Karabakh?

In the Soviet era, due to the targeted policy of the Azerbaijani authorities, the proportion of the Armenian population in Nagorno-Karabakh increased only slightly. From 1926 to 1989, the NKAO’s Armenian population increased from 111,700 to 145,500, while the Azerbaijani population increased three times: from 12,600 to 40,000. The demographic changes, in general, reflected the situation in the social, economic and cultural spheres, which was a continuation of the policy of the Azerbaijani authorities of infringing on the interests of the Armenian people and “ousting” them from the region.

However, it was the segregation in the national and cultural sphere that most acutely echoed in the mass consciousness of Armenians. Out of the numerous Armenian churches on the territory of the NKAO, none were permitted to function, whereas mosques operated to meet the spiritual needs of the Azerbaijani population. Armenian, as a language, had practically been censored from official use. The number of Armenian schools was reduced yearly; there were almost no textbooks in Armenian since it was forbidden to use textbooks published in Armenia. History textbooks–particularly of Armenian history–compiled by Azerbaijani authors contained distorted narratives offending the feelings of the national identity of Armenians.

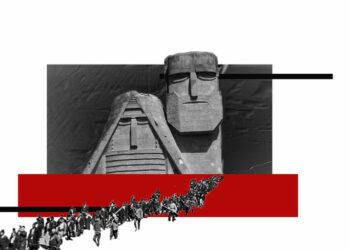

1965 was considered a year of national awakening in the Armenian SSR, in terms of voicing tabooed questions on the Armenian Genocide. In Artsakh, there was a parallel movement, despite its milder manifestations. In particular, the cultural monument “We are our mountains” was created in 1965 and soon became the symbol of national identity and unity. In the following year, a group of Artsakh Communists signed a letter to the Soviet leadership, underlining the discriminatory economic policies carried out by the Azerbaijani SSR, meanwhile referring to the centuries-long history of Artsakh. Similar attempts to establish historical bridges between the past and present occurred in 1972 and 1975 as well; however, no endeavor came to its conclusion as they did not align with Soviet political priorities.

Q6: Why did some toponyms in Nagorno-Karabakh have non-Armenian names?

There are two main reasons why predominantly Armenian-populated regions renamed their toponyms during the late Middle Ages. The territory of Eastern Armenia, before being conquered by the Russian Empire, was under the rule of Persia. Persian rulers granted the Armenian Meliks of Artsakh the right to self-governance in their territories, and Meliks had to recognize the dominance of the Shah in return.

Before becoming a part of the Russian Empire, Karabakh was reorganized as a khanate with a Muslim khan as an intermediary between the meliks and the Shah. Thus, the first reason for the changes of the toponyms was the Muslim rule during which the settlements were assigned non-Armenian names. The second reason was connected with Russian rule. The Armenian population was bilingual, while the Muslim population spoke only their native Turkic language. During the Russian rule, the names of the settlements were registered in the Russian census and tax records in Turkic languages in order to be understandable for everyone in the region.

Q7: How did Nagorno Karabakh acquire its independence and on what legal basis?

Inspired by Gorbachev’s policies of perestroika (restructuring) and glasnost (transparency/openness), on February 20, 1988, a special session of the NKAO Council of People’s Deputies passed a decision to appeal to the Supreme Councils of the Azerbaijani SSR and Armenian SSR. The decision claimed “to demonstrate a sense of deep understanding of the aspirations of the Armenian population of Nagorno-Karabakh and resolve the question of transferring NKAO from the Azerbaijani SSR to the Armenian SSR.” In response to the democratic expression of will by the Artsakh Armenians, on February 27-29, massacres of the Armenian population were organized in the Azerbaijani city of Sumgait, which was followed by killings, rapes, pogroms and looting. After Sumgait, a wave of pogroms swept across the whole territory of Azerbaijan, including Baku and Kirovabad (modern-day Gandzak).

On August 30, 1991, the Supreme Council of Azerbaijan adopted a declaration on the restoration of state independence of the Azerbaijani Republic as a successor of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic, which existed from 1918 to 1920. On September 2, 1991, based on Article 3 of the USSR Law on “the procedures of the resolution of problems on the Secession of a Union Republic from the USSR,” a joint session of deputies of all levels of the NKAO and the Shahumyan region proclaimed the independence of the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic (NKR). In particular, the declaration notes the expression of the “will of the people, manifested by the actual referendum and enshrined in the decisions of the NKAO authorities and the Shahumyan region in 1988-1991, its desire for freedom, independence, equality and good-neighbourliness.”

Just a few days before the official collapse of the Soviet Union on December 26, 1991, on December 10, a referendum was held in Nagorno-Karabakh with the overwhelming majority of the population (99.98%) voting in favor of full independence from Azerbaijan. Parliamentary elections in NKR were held on December 28, which then formed the first government. The NKR’s Azerbaijani population refused to participate in the referendum, instead supporting the aggression unleashed by the Azerbaijani authorities against Artsakh by taking an active part in it.

Q8: How did the Nagorno-Karabakh War of Independence proceed and end?

The independent NKR government went on to work under the conditions of total blockade, war and aggression unleashed by Azerbaijan. Utilizing the USSR’s 4th Army’s weaponry headquartered in its territory, Azerbaijan engaged in wide-scale military operations against Nagorno-Karabakh. As it is well known, the war continued with varying success from the fall of 1991 until May 1994. There were times when almost 50% of the territory of Nagorno-Karabakh was captured, while the capital city of Stepanakert and other residential areas were relentlessly subjected to massive air and artillery bombardment.

The NKR’s defense forces were able to liberate the city of Shushi in May 1992 and open a corridor into the Lachin region, creating an opportunity to reconnect the NKR to Armenia, breaking through the years-long blockade. In June-July 1992, the Azerbaijani army captured the NKR’s entire Shahumyan region, and portions of the Martakert, Martuni and Hadrut regions. To resist Azerbaijani aggression, life in the NKR completely focused on the military effort. The NKR State Defense Committee was formed on August 14, 1992. Separate defense detachments were reconfigured, forming the Nagorno-Karabakh Defense Army, based on the principles of discipline and central command chain.

The NKR Defense Army succeeded in liberating previously occupied territories from Azerbaijan and, during military engagements, took over a few regions bordering the NKR that had been used as firing lines. The creation of this security zone precluded the immediate threat facing the peaceful population of the NKR. With the mediation of Russia, Kyrgyzstan and the CIS Interparliamentary Council, Azerbaijan, Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia signed the Bishkek Protocol in the capital city of Kyrgyzstan on May 5, 1994. According to that document, parties to the conflict agreed to a cease-fire, effective from May 12, 1994 onward.

Q9: Which organization has the legal mandate to facilitate the peace process?

In March 1992, the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (since 1995 known as the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, OSCE) joined the settlement process of the conflict. In 1997, the institute of co-chairmanship of Russia, France and the U.S. of the OSCE Minsk Group was created, which since then has been the only agreed format, with the mandate from the OSCE, to conduct mediating activities for the peaceful settlement of the Karabakh conflict. The Minsk Group, consisting of the U.S., Russia, France, Belarus, Germany, Italy, Sweden, Finland, Turkey, Armenia and Azerbaijan, remains the leading negotiating platform.

Q10: Is it really the case that Armenia does not comply with four UNSC resolutions which were adopted in 1993, as Azerbaijan frequently claims?

No, it is a clear example of distorting the facts and manipulating the content of the UNSC resolutions. It is also an indication of disrespect to the United Nations and its member countries. Here are the key takeaways from these resolutions. From April to November 1993, the UNSC adopted four resolutions (N. 822, 853, 874, 884), aimed at stopping the fighting in Karabakh and de-escalating the situation. The resolutions are binding; therefore, before Azerbaijan accuses the Armenian sides of not following the resolutions, Azerbaijan should comply with them. Below are some of the points which remain neglected by Azerbaijan.

- The first UNSC resolution (822) “demands the immediate cessation of all hostilities and hostile acts with a view to establishing a durable ceasefire.” From April 1993 to May 1994, and since 2008, Azerbaijan has constantly violated the ceasefire regime preventing the emergence and further development of the conflict resolution process as well as confidence-building measures.

- UNSC resolutions do not refer to the involvement of the Armenian army in the NK conflict; they mention only “local Armenian forces,” i.e. the Nagorno-Karabakh Defense Army, affirming that this is a conflict of a local population.

- UNSC Resolution N. 853 of July 1993 recognizes the Armenians of Karabakh as a “party.” It is a requirement from the international community to Azerbaijan to sit down with Karabakh Armenians. Azerbaijan has not adhered to this binding document.

- By direct involvement in the Karabakh conflict, Turkey violates UNSC article 10 of resolution N. 853, which urges states to refrain from supplying weapons and munitions to conflicting parties.

- UNSC resolution N. 874 article 8 supports the development of the OSCE monitoring mission. Azerbaijan fails to adhere to the legally-binding resolutions and constantly urges to change the negotiation format by engaging Turkey.

- The Azerbaijani blockade against Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh still remains in force, thus violating Article 5 of the UNSC resolution N. 874, which calls for removing all obstacles to communications and transportation.

- Article 10 of UNSC N. 874 and article 6 of UNSC N. 884 urge “all states in the region to refrain from any hostile acts and from any interference or intervention that would lead to the widening of the conflict and undermine peace and security in the region.”

Thus, the unconditional and comprehensive support of Turkey to Azerbaijan severely violates the resolutions mentioned above.

Q11: What were the main approaches to the conflict resolution proposed by the OSCE Minsk Group?

Between 1997 and 1998, the OSCE has considered several proposals for conflict resolution. The “package approach” assumes that all the debatable issues should be resolved at once without any delay. The package settlement of the conflict includes the withdrawal of the forces from the territories under Armenian control, security guarantees, the return of refugees and IDPs, the introduction of the trade and communication links and deploying international peacekeepers. The status of Nagorno-Karabakh to be determined after the implementation of these measures. Before the implementation of all the above-mentioned measures, Nagorno Karabakh will be granted internationally recognized interim status and self-governance but will be considered Azerbaijan`s territory.

The “step by step” approach is staged as it assumes that Armenian forces should first withdraw from the territories gained (except for Lachin) and only then move to the discussion of the Nagorno-Karabakh’s political status. However, the absence of the security guarantees and postponement of the status determination are the main obstacles causing dissatisfaction of the NK and Armenian side.

The “common state” approach proposed to determine Nagorno-Karabakh’s status as a “state and territorial entity in the form of a Republic, which constitutes a common state with Azerbaijan within its internationally recognized borders.” This solution entailed creating horizontal ties between NK and Azerbaijan, introducing a federal system, similar to Bosnia and Herzegovina. Azerbaijan rejected this proposal claiming that it de facto grants independence to Nagorno Karabakh.

Q12: What tangible steps did the OSCE Minsk Group undertake to reconcile the disagreements between Armenia and Azerbaijan?

Since 1999, the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict resolution process has been carried out through the meetings of presidents and other official representatives of Armenia and Azerbaijan, as well as by means of shuttle visits of the OSCE Minsk Group Co-chairs to Stepanakert, Baku and Yerevan. On January 26 and March 4-5, 2001, two rounds of negotiations were held between the President of Armenia Robert Kocharyan and the President of Azerbaijan Heydar Aliyev in Paris, with the participation of the President of France Jacques Chirac. The meeting in Paris was followed by negotiations between the Armenian and Azerbaijani presidents in Key West, Florida from April 3 to 7, 2001. However, no concrete results were achieved during the negotiations in Key West. The agreements reached in Key West have not been realized, primarily due to the subsequent rejection of them by President Heydar Aliyev.

On June 29, 2007, during the OSCE Council of Ministers of Foreign Affairs in Madrid, the text of the basic principles for conflict settlement (subsequently called “the Madrid principles”) was officially conveyed to the ministers of foreign affairs of Armenia and Azerbaijan. On July 10, 2009, the presidents of the OSCE Minsk Group Co-chair states (Russia, France and the U.S.) adopted a joint statement during the G8 summit in L’Aquila, Italy, revealing the main notions proposed by the mediators on the basic principles of a settlement. Similar statements were adopted by the presidents of Russia, France and the U.S. during the G8 summits in Muskoka, Canada on June 26, 2010, in Deauville, France on May 26, 2011, in Los Cabos, Mexico on June 18, 2012 and in Enniskillen, Northern Ireland on June 18, 2013.

After the first joint statement of the OSCE Minsk Group Co-chair states (L’Aquila, 2009), the Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic made a statement on July 17, 2009, stressing the necessity to restart the distorted negotiation process, to return the NKR as a full-fledged side to the negotiations and to transform the basic principles of the settlement. The position of the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic remains unchanged.

Q13: What was Russia’s role in the conflict resolution process?

Both during the conflict and after the ceasefire in 1994, Russia played an instrumental role in the conflict. However, it’s more active participation came between 2008 and 2011, when Russian President Dmitriy Medvedev invested a substantial amount of time and resources to hold trilateral meetings with the Presidents of Armenia and Azerbaijan. During three years, nine trilateral summits were held. Due to Medvedev’s efforts, for the first time since 1994, Sargsyan and Aliyev adopted a joint declaration in the Meyendorff castle, not far from Moscow, in November 2008. It aimed to initiate a number of confidence-building measures to improve the security in the region. Medvedev’s active involvement in the negotiation process was meant to yield tangible results in June 2011, when he invited the two presidents to Kazan to sign the document on the basic principles. However, despite Medvedev’s hopes and assurances and the pressure of the international community, the leaders failed to agree on the previously negotiated principles. According to different accounts, during the meeting, Aliyev presented around 10 reservations and conditions to resume the negotiations and sign the basic principles. The process came to a halt and the international community became deeply skeptical about the conflict resolution prospects.

Since Putin’s re-election as president, he reiterated several times that Russia will support any agreement that the parties can reach. However, the positions of the parties became more and more difficult to reconcile and Russia’s role became to serve as “firefighter” by not allowing major flare-ups on the Line of Contact. In April 2016, Russia mediated the ceasefire during the four-day escalation of the conflict.

Q14: How did the war influence state building in Artsakh?

Despite the war, Nagorno-Karabakh has never ceased its state building process. From 1991 to 2020, the NKR held six presidential and seven parliamentary elections and three referenda. Each time, the elections were held according to international standards in a transparent, free and fair atmosphere. Power transfer was peaceful each time. In addition to the social conditions of the people and strengthening of public institutions and local government, Artsakh has also worked on improving its foreign relations. Since 2012, nine U.S. states (California, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Michigan, Georgia, Hawaii, Maine, Louisiana and Colorado), the city councils of Alfortville, Limonest, Vienne in France, the Italian cities of Milan, Cerchiara di Calabria and Palermo, Glendale City Council, Flower City Council in California, the city of Fort Lee, New Jersey and the Australian state of New South Wales supported the right of the people of Nagorno-Karabakh to self-determination. The resolutions passed by these states were not only unprecedented but were also inconsistent with the foreign policies of their federal governments.

Q15: What caused the escalation of the conflict in 2016 (The Four-Day April War)?

On April 1, 2016, Azerbaijan flagrantly violated the ceasefire and its commitment to the non-use of force undertaken within the Nagorno-Karabakh peace process under the auspices of the OSCE Minsk Group Co-Chairs. After the ceasefire of 1994, the scale of the military actions initiated by Azerbaijan was the largest. The Azerbaijani Armed Forces resorted to a large-scale military offensive against Nagorno-Karabakh. These actions were accompanied by atrocities against both military servicemen and innocent civilians. Basically, it was the continuation of the massacres and ethnic cleansing that Azerbaijan committed against the Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh in the early 1990s.

The analysis of Azerbaijan’s military actions also shows that it adopted blitzkrieg tactics and with its offensive aimed to reach quick success. Although both sides had losses, the initial aim failed because of the appropriate defensive military actions of the Armenian side. On April 2, then-President of Armenia Serzh Sargsyan held a National Security Council session and announced the losses of the Armenian side. In contrast to the aggression of the Azerbaijani side, Serzh Sargsyan invited OSCE ambassadors on April 4 to reach a joint agreement on ceasing the military actions. He announced that further intensification of military operations could lead to unpredictable and irreversible consequences, including a large-scale war. On April 5, with Russia’s initiative, the Armenian and Azerbaijani Heads of Army’s General Staff came to a verbal agreement in Moscow to cease the fighting.

Compiled by: AUA MPSIA Class of ’21

Most of the information for this article taken from the Artsakh Foreign Affairs Ministry

also read

The UN, International Organizations and States Are Obligated to Provide Humanitarian Aid to Nagorno Karabakh: Here Is Why

The humanitarian emergency in the Republic of Nagorno Karabakh requires the engagement of humanitarian and donor organizations, without regard to its international recognition, its present or future status.

Read moreWar, Nothing But War: The Virtue of Brute Force and the Shortcomings of Diplomacy

The narrow geopolitical framework of the three-decade-old Karabakh conflict is now threatening to become a Eurasian nightmare: Turkey's involvement has sensationalized the war, Iran’s unease has reinforced the confusion, while Russia's perceived passiveness has created much regional anxiety.

Read moreRemedial Rights in International Law and Their Relevance to Artsakh

In light of the existential threat, high probability of ethnic cleansing and the already imminent humanitarian crisis in Artsakh, the international community has an obligation to grant remedial recognition to Artsakh.

Read moreThe Responsibility to Protect, Remedial Secession and Nagorno-Karabakh

Does the armed conflict of international character waged by Azerbaijan and Turkey against Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh warrant an international recognition of Artsakh’s remedial secession?

Read moreFighting for Existence: Armenia Battles Two Repressive Regimes and Mercenaries

Given the geography, tactics and methods of the Azerbaijani offensive, the autocratic regime of Ilham Aliyev is aiming to forcibly occupy the territory of Artsakh through committing large-scale atrocities.

Read moreYes, It Is Genocidal

The inclusion of the term genocide is not being loosely thrown around. As the war rages on, the potential for genocide against ethnic Armenians in Artsakh is very real and highly probable, writes Suren Manukyan.

Read morephoto stories

A Record of War

Photojournalist Eric Grigorian captures the devastation of war, its destruction of lives, heritage sites and schools. A portrait of a nation at war, of a capital where the elderly and the grieving live underground.

Read moreStepanakert Under Attack

As Stepanakert, the capital of Artsakh came under continual shelling by Azerbaijani armed forces, photojournalist Eric Grigorian captured the devastating aftermath.

Read moreMartakert: A City Fractured

The city of Martakert in Artsakh came under heavy shelling twice since the start of the war. This photo story captures the aftermath.

Read moreStepanakert Shelled

The capital of the Republic of Artsakh was shelled twice today by Azerbaijani armed forces injuring civilians and damaging buildings and infrastructure. Photojournalist Eric Grigorian captured these images in Stepanakert.

Read moreA Home to War

These powerful images capture fragments of life in Artsakh, a place that is boundlessly resilient yet has too often become a home to war.

Read more